The Doomsday Clock is broken

Plus: the Democrats need to win more swing states from 2032, the urban transformation in the nineteenth century, and more

Welcome to The Update. In today’s issue:

The Doomsday Clock is broken

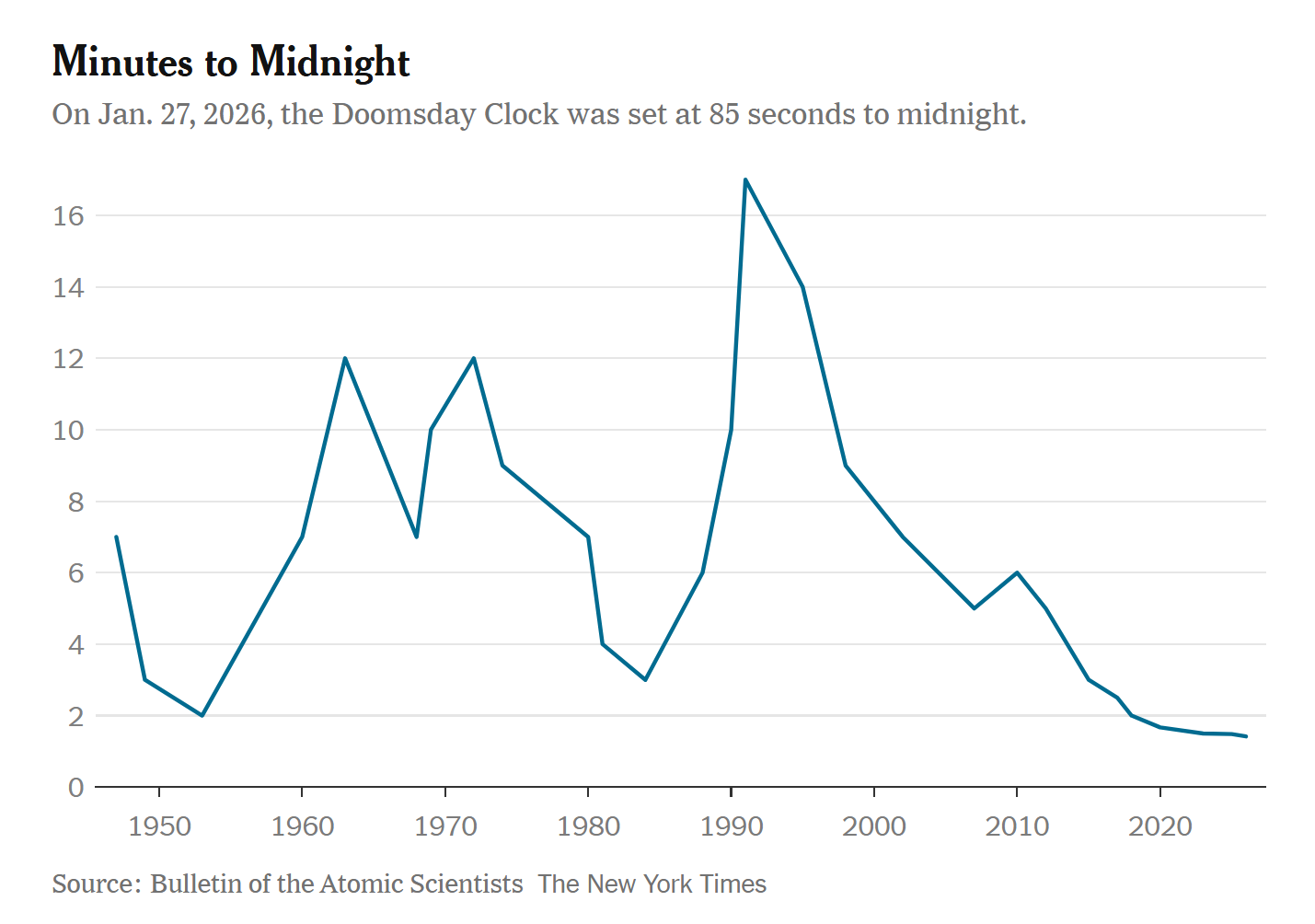

Since 1947, the Bulletin of the Atomic Scientists has updated the Doomsday Clock, intended to ‘warn the public about how close we are to destroying our world with dangerous technologies of our own making’. On Tuesday, it was reset to 85 seconds to midnight – the most alarming estimate so far. But can we trust what the clock is saying? As Andy Masley points out, it put us closer to midnight in 2012 – not a particularly dramatic year, as I recall it – than during the 1962 Cuban Missile Crisis.

And there’s another problem with the Doomsday Clock. Given that the world hasn’t come to an end, is it really plausible that the risks have been so high for all these years? As a day is 1,440 minutes, we were supposedly 99.5 percent of the way to midnight already in 1947 – and since then, we’ve stayed in a band between 98.8 percent (1991) and 99.9 percent (today). Anything that wobbles that close to an edge eventually falls off. Since we’re still around, the natural conclusion is that for the great majority of these years, we weren’t actually close to destruction.

Democrats need to win more swing states from 2032

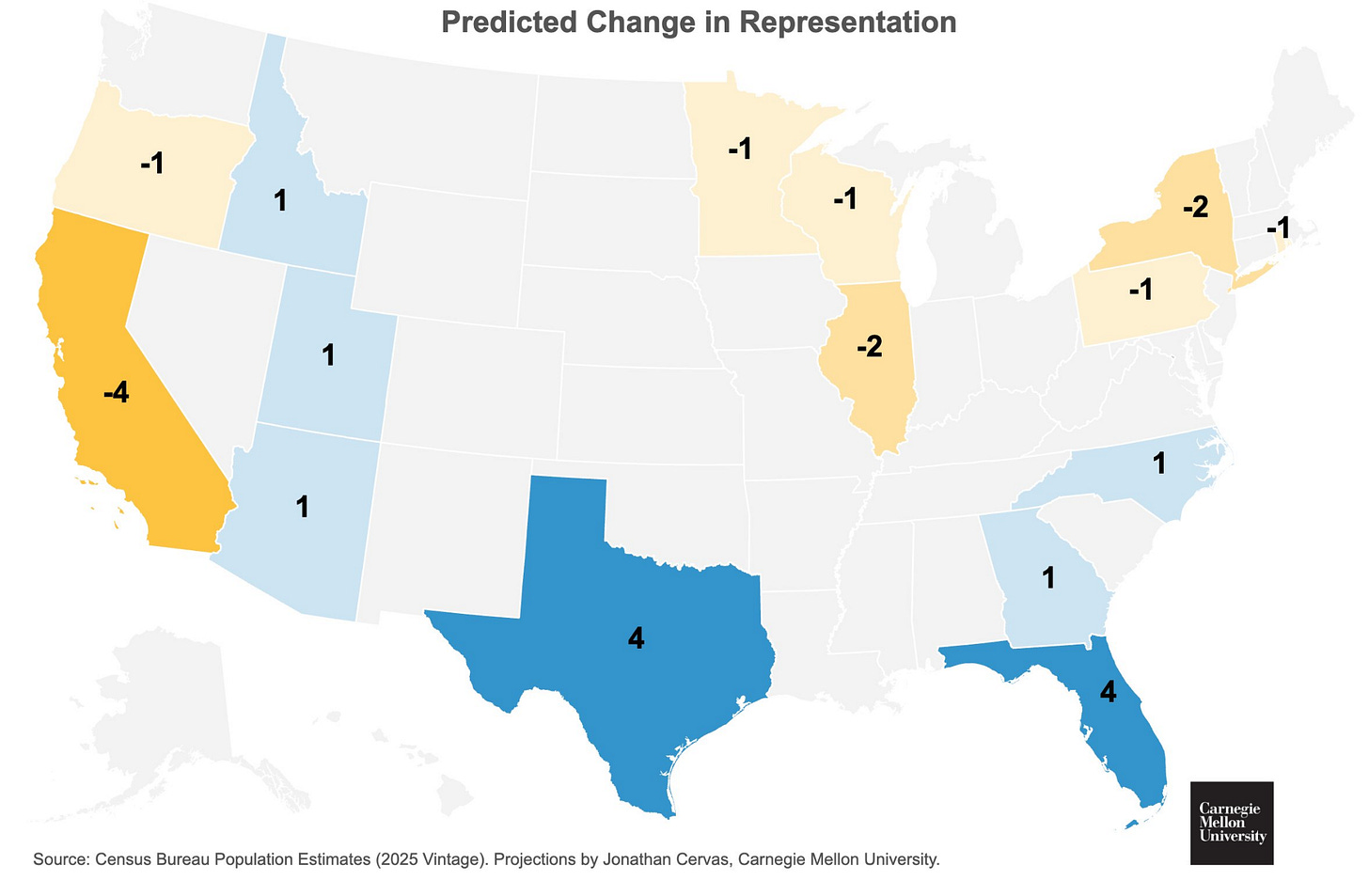

New population estimates from the US Census Bureau show that Americans are moving toward Republican states. Based on these estimates, political scientist Jonathan Cervas has published a projection of how votes in the Electoral College – which ultimately elects the president – and seats in the House of Representatives might be reallocated in 2030. States where Republicans normally win are projected to gain ten electoral votes, whereas states that are reliably Democratic are projected to lose eleven – the last vote going to a swing state. This means the Democrats may need one or two additional swing states to win the presidency from 2032.

Projected seat changes in the House of Representatives and corresponding changes in Electoral College votes in 2030.

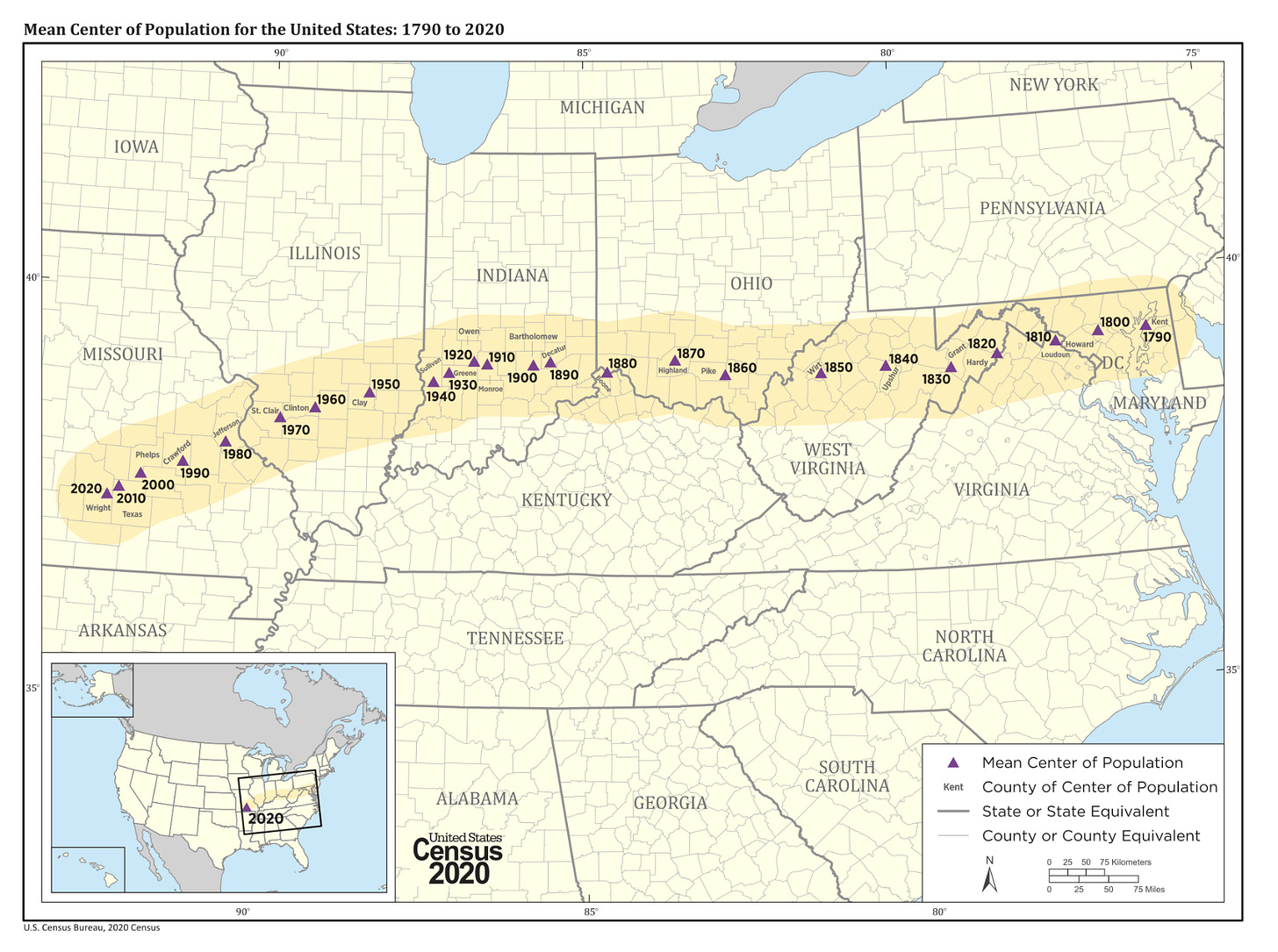

Another thing I found interesting about this map is what it says about long-running shifts in where Americans live. The mean center of the US population moved west throughout the nineteenth and twentieth centuries, but this trend has slowed down in recent decades – and the reapportionment projection suggests it is slowing further still. Instead, the primary trend is increasingly toward the south, thanks to the growth of states like Florida and Texas.

How cities were transformed in the nineteenth century

Nineteenth-century cities grew ferociously: New York’s population was a hundred times larger in 1914 than in 1800, and some cities – like Toronto and Chicago – expanded even more. In an article for Works in Progress, Samuel Hughes asks how they managed this rapid growth. The period has a reputation for doctrinaire laissez-faire, but while cities did take a light touch on individual buildings, they were far more interventionist on infrastructure, often turning rail transport and utilities into monopolies. In some cases, their interventionism went further than people would accept today – like compulsory purchases to push new roads through existing neighborhoods.

As Samuel describes in fascinating detail, the nineteenth century was an incredibly transformative period for cities in industrializing countries. The urban landscape was reshaped by everything from sewer systems to underground railways – and in the US even skyscrapers. But interestingly, economic growth was actually slower than it’s been in the last 50 years, when the urban environment has changed far less. It’s a reminder that growth rates are not as strong a proxy for societal change as one might think.

Why we overestimate the differences between what humans and AIs can do

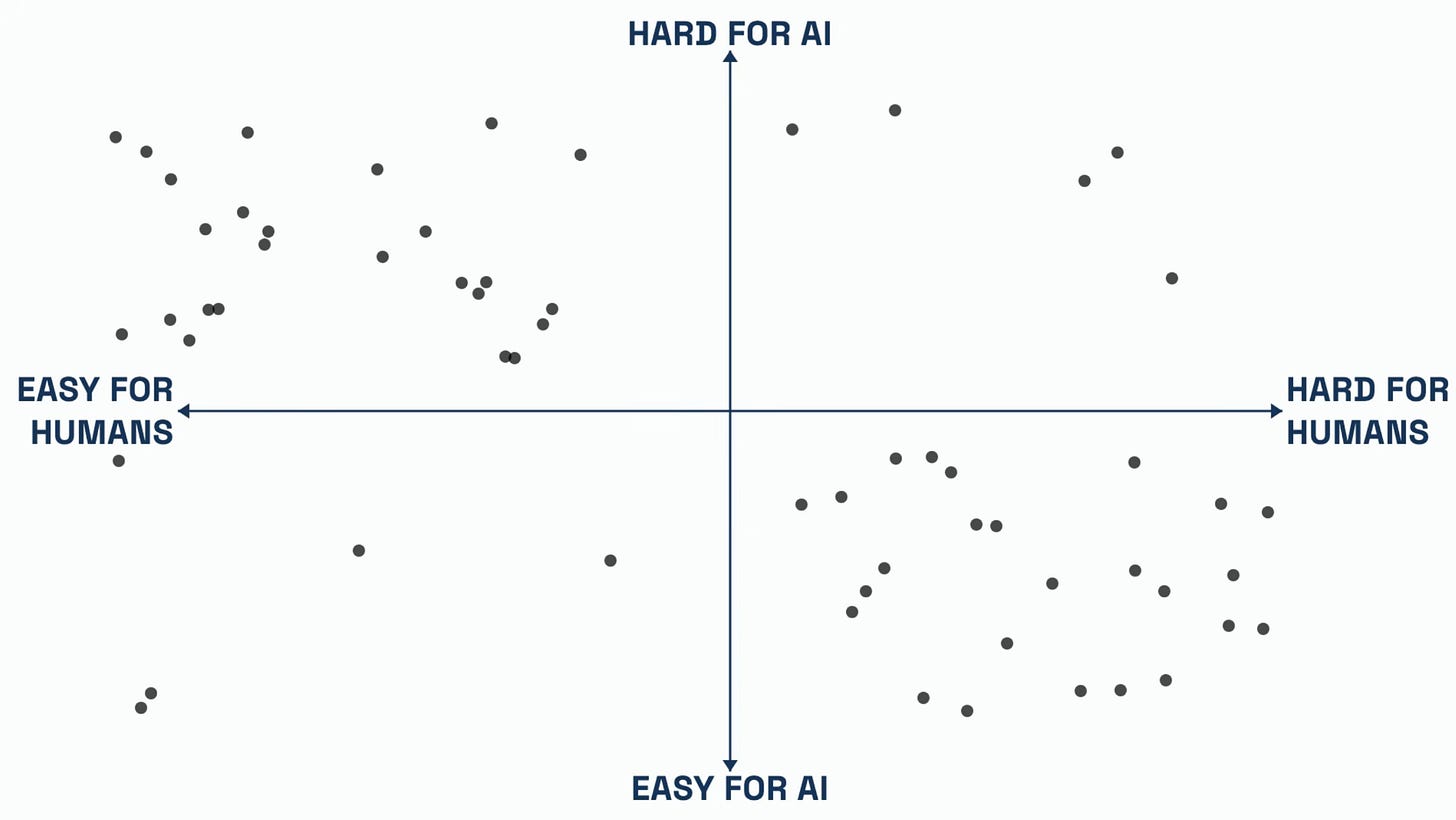

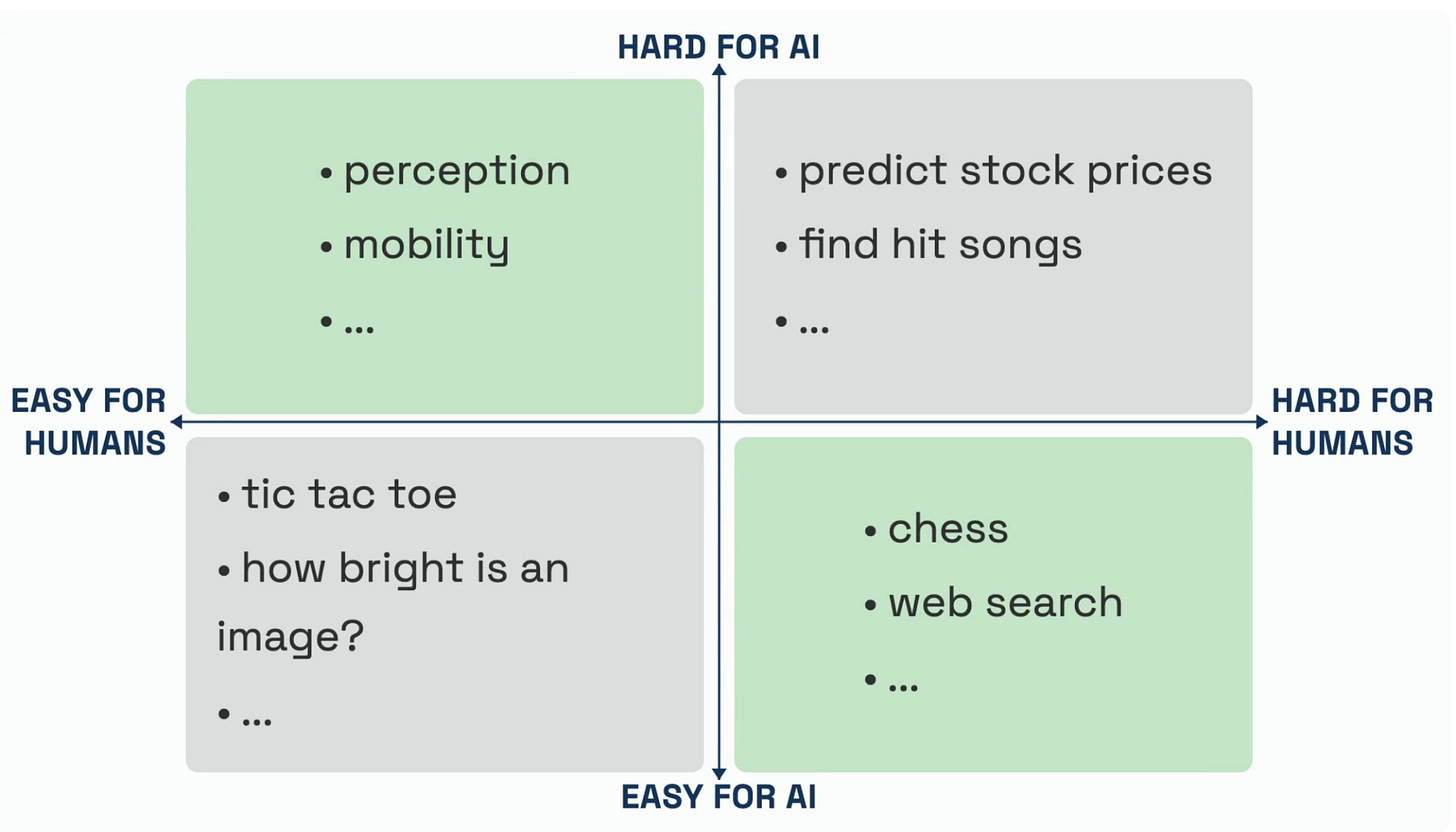

In the debate about the future impact of AI, people often say that tasks that are hard for humans are easy for AIs, and vice versa – an idea sometimes called Moravec’s paradox. We find chess difficult and folding clothes easy, whereas for AIs – and the robots they guide – it’s the other way around.

But does this pattern really hold? In a new video, computer scientist Arvind Narayanan argues that it’s an illusion resulting from selective attention. There are many problems that are easy for humans and AIs alike – like doing basic sums – and many that neither of us can solve, like predicting tomorrow’s stock prices. But these similarities are so banal that we never talk about them. That leads us to overestimate the differences between what humans and AIs can do.

I think this is right. It’s true that the way AIs process information is quite different from ours. That’s why we can solve some problems they can’t and vice versa. But there’s another factor: the intrinsic difficulty of the problems. Some problems are so easy that any intelligent system can solve them, whereas others are so hard that it doesn’t matter if you’ve been optimized for problems of that kind. I think this factor means that intelligent systems with very different origins will have more correlated capabilities than you might naively think.

Is our adolescence about to begin?

‘How did you survive your technological adolescence without destroying yourselves?’ In the 1997 movie Contact, that’s the question Jodie Foster says she’d ask an advanced alien civilization. In a new essay, Anthropic CEO Dario Amodei argues we must now ask ourselves how we can survive our own adolescence, due to the breathtaking speed of AI progress. He discusses five types of risks:

AI systems escaping our control

AI lowering barriers to biological weapons and other destructive technologies

Bad actors using AI to seize or entrench power

Severe economic disruption with harmful consequences

Further indirect effects we cannot now foresee

Dario expects us to face these risks sooner rather than later. In his view, we may have only a year or two before what could be the final stage: AI systems that can autonomously drive their own progress.

That’s all for today. If you like The Update, please subscribe and share with your friends.

Highly recommend the Doomsday Machine by Dan Ellsberg if you don’t fancy sleeping tonight. We are rather lucky to be here…

Yes. To the doomsday clock. Also the signs of the end times--you know that we're about to have "rapture" and "tribulation"...apocalypse. I means things did suck not long after Jesus death, maybe he was right, but the idea that this is coming for all of us, predicted by current events of a thousand years and, silliest of all, quoting the verse saying people who denied these signs, whose grandchildren died haven never seen end times either, were somehow bad/wrong.