Why we should think more like economists

Plus: British income inequality at 40-year low, why it’s good news that more people are dying of cancer, and more

Welcome to The Update. In today’s issue:

China’s falling birth rates will have geopolitical consequences

In brief: Harvard caps A grades, the cost impact of obesity drugs, and more

Why we should think more like economists

In a recent interview, Jon Stewart tried to correct economist Richard Thaler’s humdrum claim that a carbon tax sets prices ‘so that you have the incentive to act in a way that’s best for society’.

But that’s not economics. Economics doesn’t take into account what’s best for society . . . The goal of economics in a capitalist system is to make the most amount of money for your shareholders.

It’s of course terribly arrogant to try to correct a Nobel Prize winner on the absolute basics in his own field in this way, and Stewart has received plenty of criticism from Jerusalem Demsas and Andy Masley. I don’t think he’d dare to be so ignorantly dismissive about most other fields. In many circles – including ones with a fairly intellectual self-image – economics has a low status.

I think this is a shame, because economics has a lot to offer. Jerusalem gives several examples of its positive real-world impacts, like shorter recessions and more evidence-based ways to fight global poverty. But beyond that, I think it can also correct a basic flaw in our worldview that I’ve been thinking about over the last few years.

When we try to understand society, we often neglect how people react to changing circumstances. You see it in climate discourse that assumes we’ll sleepwalk into disaster. You see it in Hollywood battle scenes, where they never retreat, no matter how bad it’s going. And you see it in the discourse about a world without work, which tends to assume we won’t be able to create new meaning. But I’ve noticed that economists don’t make this mistake as often, since the insight that people adapt to change and respond to incentives is a cornerstone of their discipline. We should all learn to think more like economists.

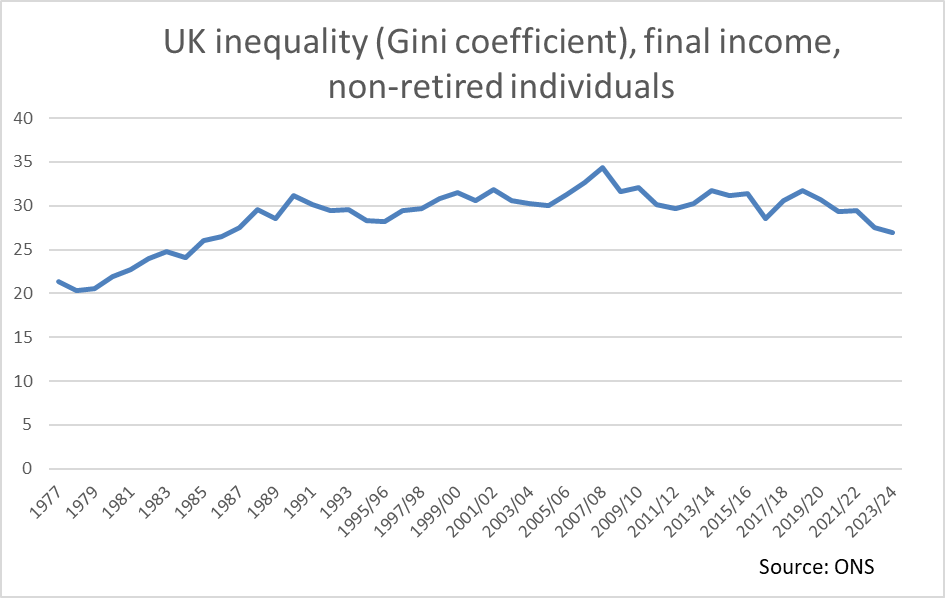

British income inequality at its lowest in four decades

Surprisingly, the 14 years of Conservative government brought British income inequality to its lowest level since 1986, when it was rising rapidly under Margaret Thatcher. Quite the change for her party.

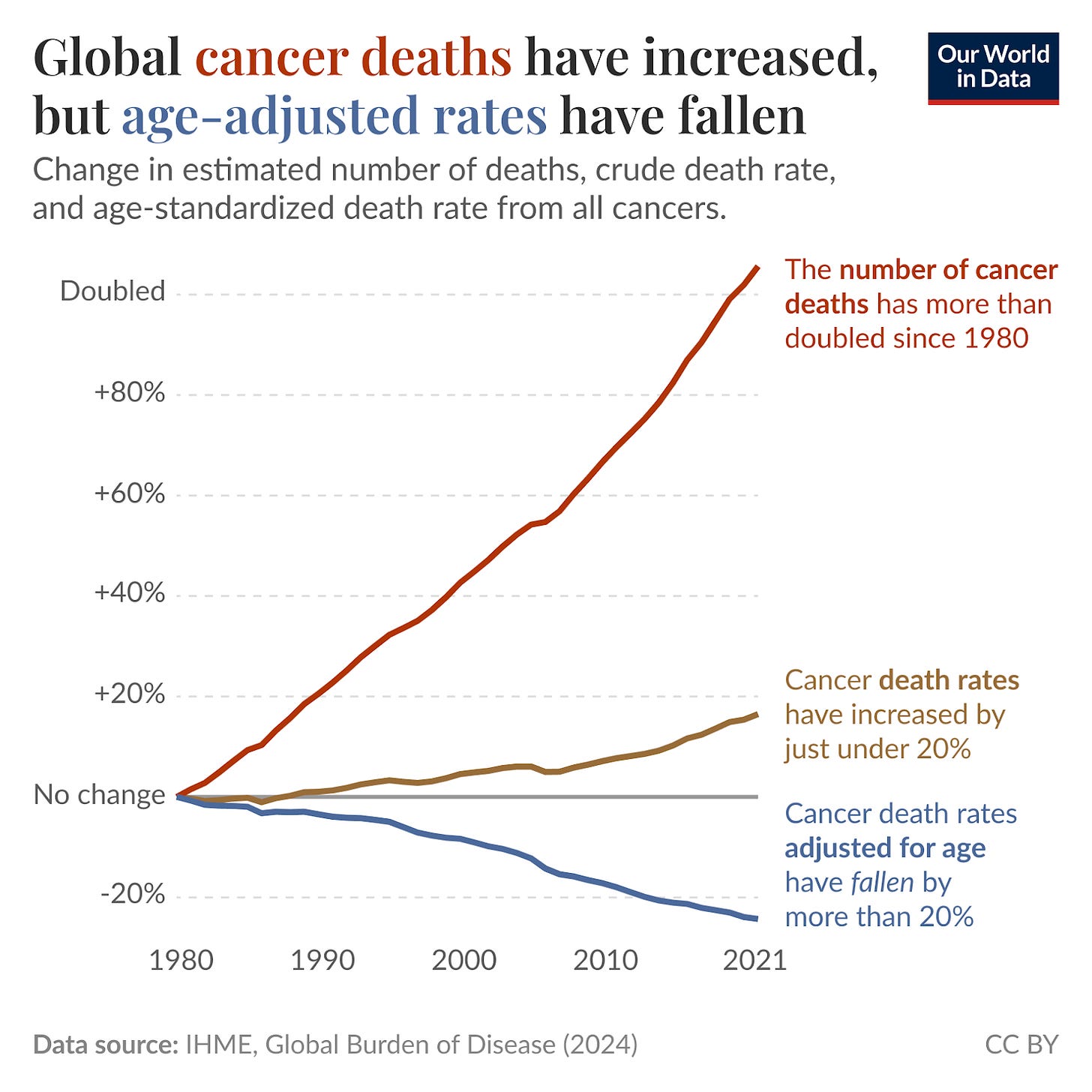

Why it’s good news that more people are dying of cancer

Since 1980, the share of the global population that dies of cancer per year has risen by almost 20 percent. But this isn’t because cancer has become more dangerous – it’s because of rising life expectancy. Cancer is much more common in old age, and more people now survive to that point. Age-adjusted cancer death rates have actually fallen by more than 20 percent.

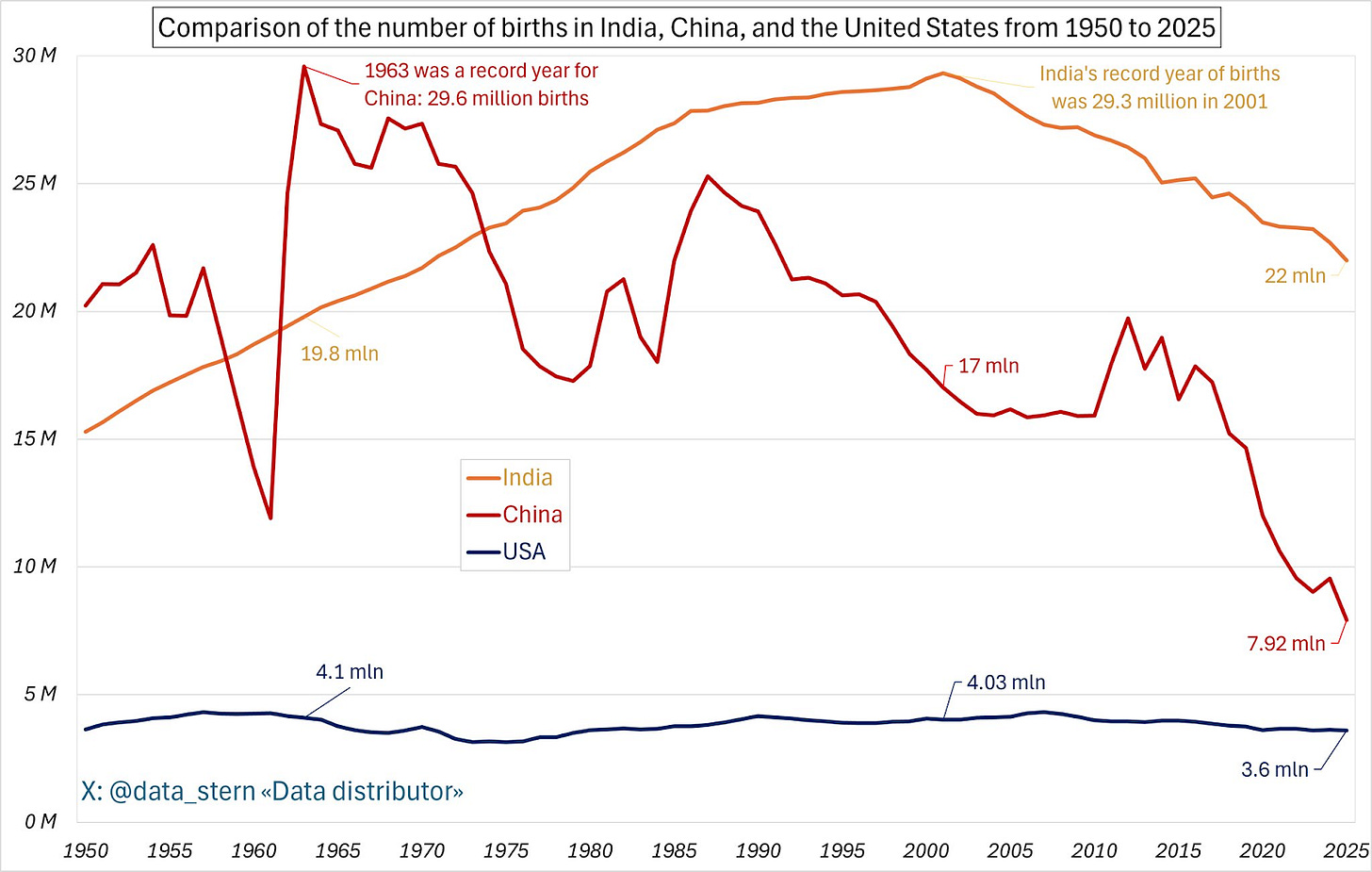

China’s falling birth rates will have geopolitical consequences

A key reason for China’s ascent as a geopolitical power is the size of its population: roughly four times that of the US. But recent birth data suggests that China’s population will shrink relative to that of the US as well as India. Whereas China had more than seven times as many newborns as the US in 1963, that ratio was merely 2.2 last year. And though Indian births are falling too, they’re still almost three times the Chinese figure. Over the course of this century, this is bound to have geopolitical consequences.

Why we shouldn’t update much on Moltbook

Kelsey Piper argues that Moltbook, the forum where AI agents discuss everything from philosophy to ‘their humans’, provides evidence about how we’ll react to risks from AI. In her view, Moltbook shows ‘we’re never going to pull the plug’.

People would ask, ‘Why don’t we just not give AIs the power to do high-stakes financial transactions or anything else that it would need to do to take power?’

To this, I think the best response has always been, ‘Have you met humans?’ If everyone gets to decide what to do, lots of people will decide to give their AI permission to do whatever it wants.

She concludes that this response has been proven right ‘because it already happened’.

But I think that’s not quite how we should interpret those who said we could pull the plug. As far as I remember, they weren’t talking about scenarios where everyone gets to decide what to do, but about government restrictions. They were saying that governments won’t sleepwalk into disaster. I agree with Kelsey that governments should gradually regulate AI more, but it’s still too early to tell whether they will. I wouldn’t update much on Moltbook.

In brief

When AI can make new discoveries, will AI companies restrict access?

How common are junk survey responses? Lizardman’s Constant revisited.

A division of USAID relaunches as a nonprofit, thanks to Coefficient Giving grant

Few Republicans willing to vote against Trump are left in Congress

How can we use AI to improve the quality of public discourse?

So far, obesity drugs haven’t reduced other healthcare costs in the US

Sharing clinical trial data drives research progress and has many other benefits

That’s all for today. If you like The Update, please subscribe and share with your friends.

Gosh, this is another incredible compilation! And I don't just say that 'cuz our kid is a PhD economist. ;-)

There's no scientific validity to economics.

https://mitpress.mit.edu/9780262049658/blunt-instrument/