Trump won’t crush the European right

Plus: the fragility of life in pre-industrial society, Americans aren’t spending it all on DoorDash, and more

Welcome to The Update. In today’s issue:

Why are humans so long-lived, and how can we live even longer?

Just the links: software stocks tumble on AI fears, geopolitical predictions, and more

Trump’s effects on European politics are overestimated

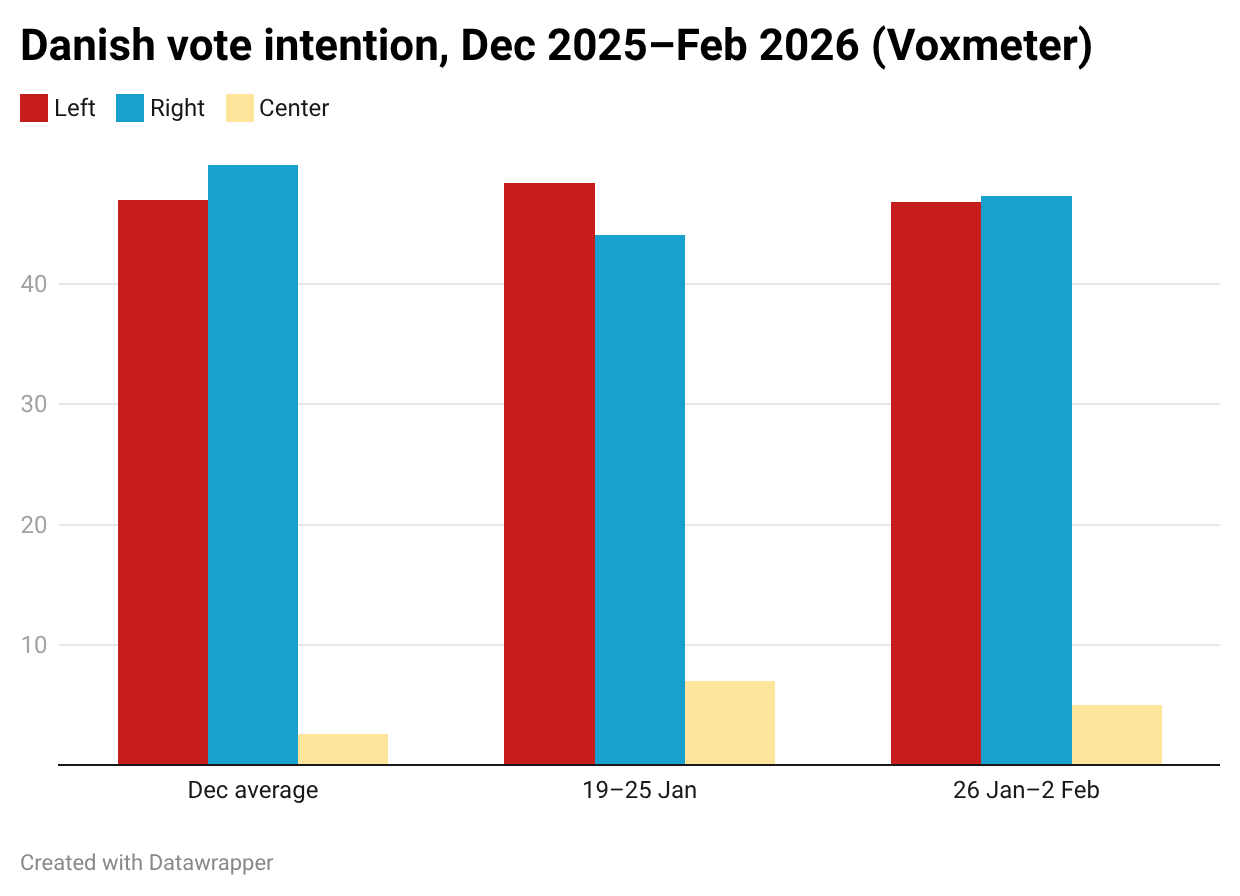

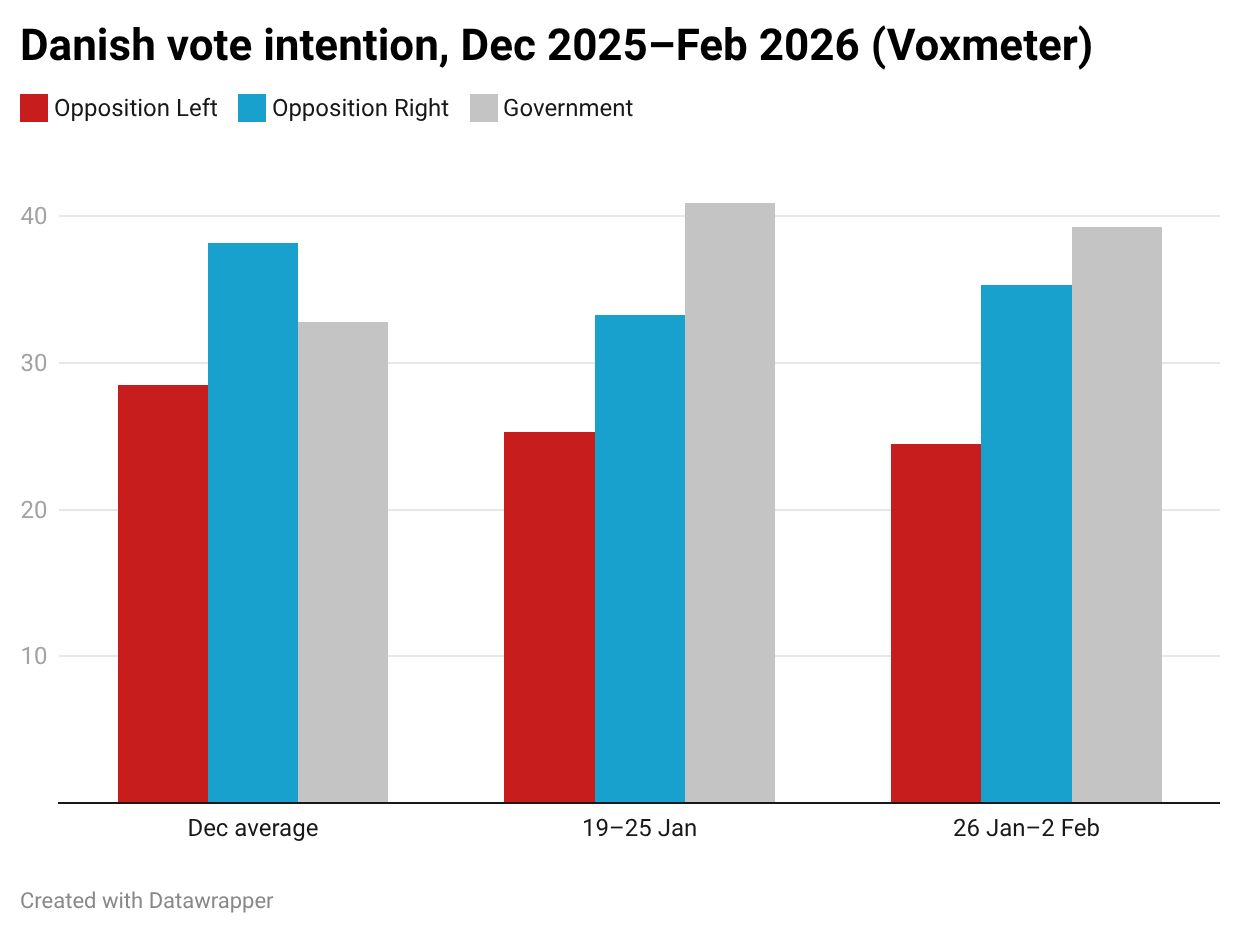

The Danish polls have seen major shifts over the Greenland crisis, but I think they’re being misinterpreted. The standard story on X has been that voters turn against the right because it’s associated with Trump – some drawing comparisons with the Canadian elections.

But I think it’s mostly a boring rally ‘round the flag effect. In recent years, most Danish governments have been either purely right-wing or purely left-wing – but since 2022, a coalition of the center-left Social Democrats, the centrist Moderates, and the center-right Liberals has been in power. These parties have struggled in the polls, but as Trump escalated his demands, the Social Democrats (led by Prime Minister Mette Frederiksen) and the Moderates (led by Foreign Minister Lars Løkke Rasmussen) gained sharply. This mechanically caused the traditional left-wing bloc to rise, as the Liberals stayed roughly flat. But beyond that, there’s little sign of a leftward push. The opposition left has lost about as much as the opposition right.

While Europe is certainly obsessed with American politics, many commentators overestimate its influence over voter behavior. The US is far away, and the association between Trump and European right-wing parties is weaker than some seem to think. Many of the European leaders he’s in conflict with are themselves right-wing.

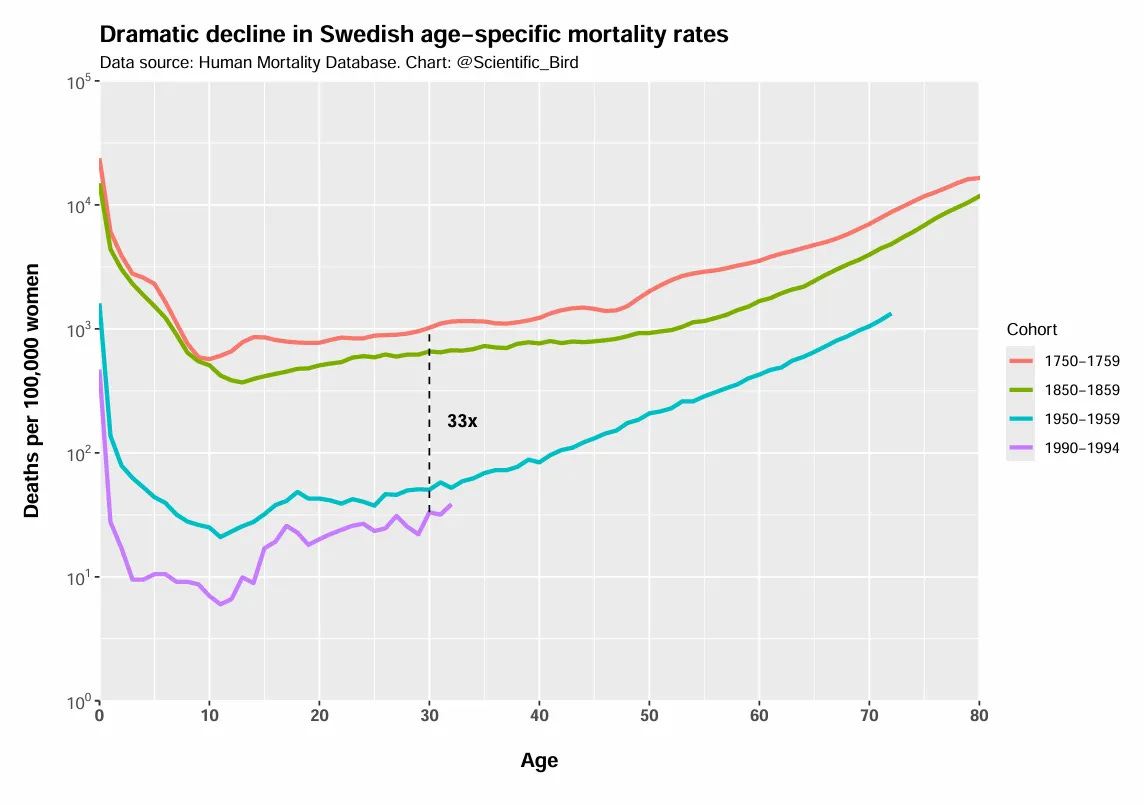

In pre-industrial society, you risked death at every age

Since the eighteenth century, life expectancy has more than doubled in most countries. What has driven this? A common misconception is that it’s overwhelmingly about lower childhood mortality – that if you survived to adulthood, your life expectancy was close to today’s. But that’s not true at all. People faced a much higher risk of dying throughout life. In the 1780s, the risk that a 30-year-old Swedish woman would die within the next year was one percent – 33 times higher than the risk a woman of that age faces today.

In any given year, there was a realistic risk you wouldn’t live to see your next birthday. When annual mortality was at its lowest – around age ten – it was what 65-year-olds have now.

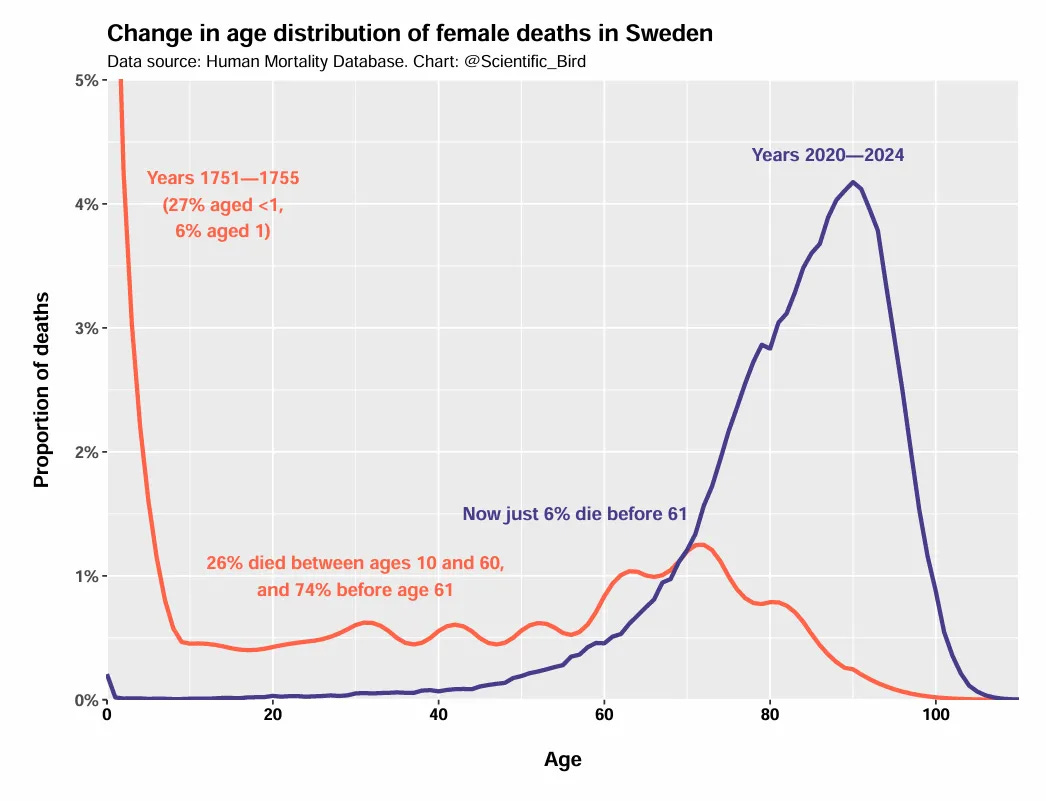

Even if it hadn’t been for childhood mortality, the age distribution of deaths would still have been extremely different from what it is today. There wasn’t much of a bump at old age, in striking contrast to today.

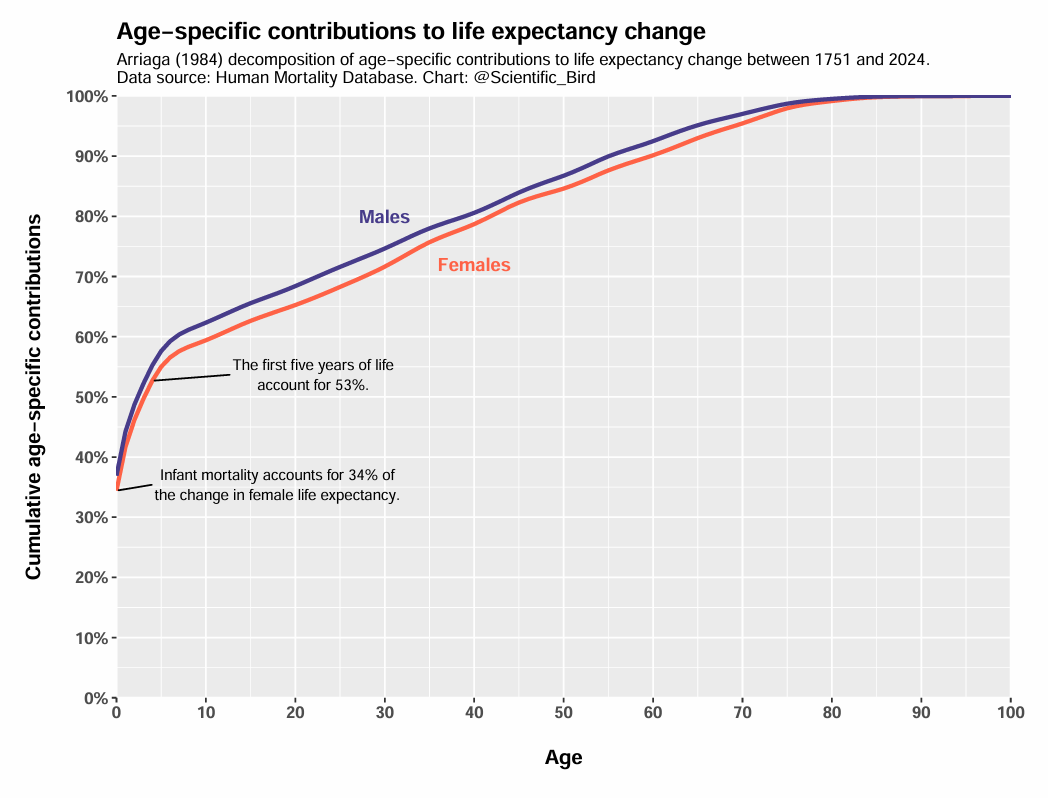

It is true that infant mortality was horrifying: one in four, so bad the chart had to be clipped. But it stands to reason that pushing a rate of one in four to almost zero is far from enough to explain that life expectancy for Swedish women has increased from around 37 to 85. In fact, falling infant mortality has contributed roughly one third of that increase, and falling mortality before the age of five roughly half.

What is gradual disempowerment?

Rob Wiblin recently interviewed David Duvenaud on gradual disempowerment – cultural drift, destructive economic incentives, or the erosion of democracy in a world with advanced AI. These scenarios are sometimes contrasted with sudden disempowerment – the hypothesis that we may suddenly lose control over powerful AI systems, potentially leading to human extinction. David says that even if that doesn’t happen, competitive dynamics could still destroy almost everything we care about.

Competitive dynamics have, of course, always been with us. One reason agriculture spread was that it simply sustained a larger population, displacing hunter-gatherers over time. More recently, market competition has created unprecedented wealth as well as environmental disasters. But David argues that AI may introduce more pernicious dynamics that could lead to gradual disempowerment.

How, exactly, should we understand this notion? The term itself suggests it’s about humanity’s power or control over these competitive dynamics. But when David introduces the thesis at the start of the podcast, he couches it in terms of negative outcomes. And that’s not quite the same, as the outcomes of competitive dynamics we don’t control aren’t always negative. How you’re supposed to use the term ‘disempowerment’ can be confusing.

Defining what it means to control large-scale cultural, economic, and political dynamics seems like a tall order. By contrast, it’s much easier to grasp what a bad outcome is. I think the outcome-focused perspective is better, and would prefer a term that made it more salient. I agree that an AI transformation would introduce new societal dynamics and challenges – much as agriculture and industrialization did – but I’m not as sure that they’ve been given the best label.

Why are humans so long-lived, and how can we live even longer?

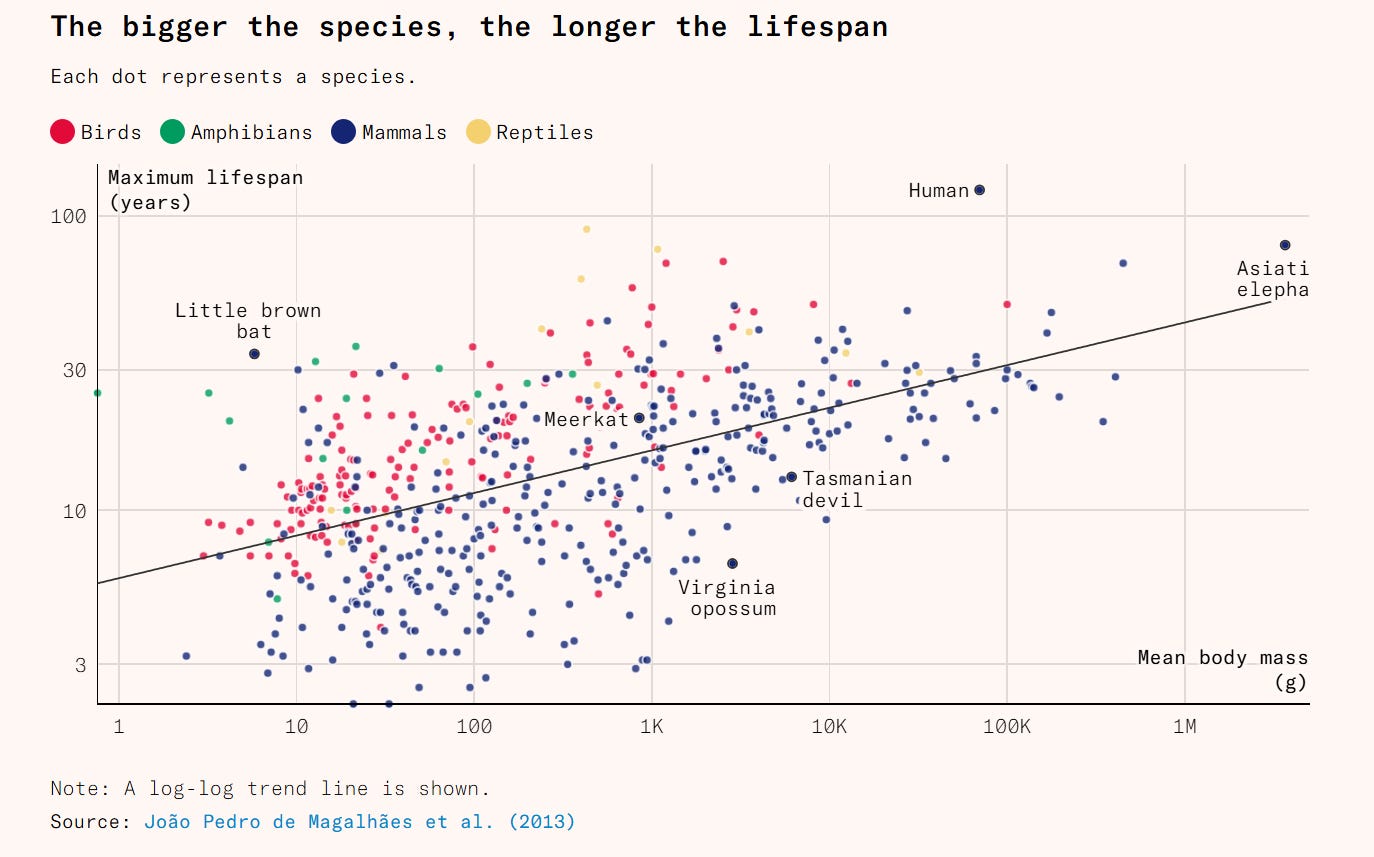

Larger animals tend to live longer, but we humans live unusually long for our size, in part because we’re surprisingly energy efficient. Still, many animals outlive us, like the Greenland shark, which can live to 400. Can we borrow their tricks? That’s the question Aria Schrecker asks in a new article for Works in Progress. We could try to mimic the Greenland shark’s slow-burning metabolism or the elephant’s genetic defenses against cancer. The sheer variation in animal lifespans should give us hope that radical life extension is possible.

Americans aren’t spending all their money on DoorDash

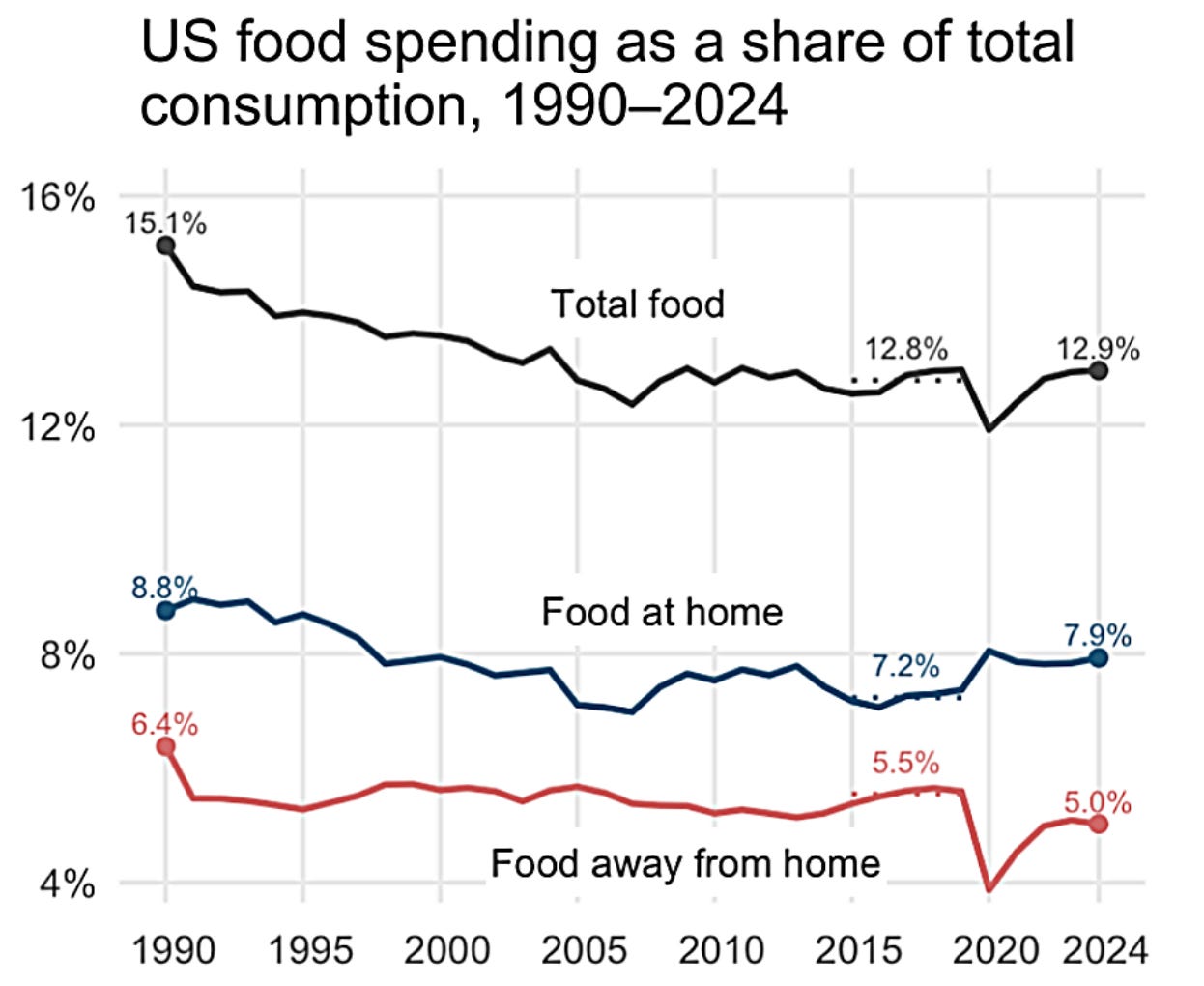

The alarmist rumors on X are not true. Mike Konczal shows that since 1990, spending on food away from home (which includes delivery) has gradually declined as a fraction of income. And total food spending has also fallen. Americans have become richer and so spend less of their income on food.

Just the links

How to use forecasting to set research priorities and allocate funding

Polymarket: 25 percent chance the US strikes Mexico by the end of 2026

Sentinel: 22 percent chance the Cuban president is out by the end of March

That’s all for today. If you like The Update, please subscribe – it’s free.