American EV sales are at their lowest since 2022

Plus: more economists in government, right-wing censorship of American students, and more

Welcome to The Update. In today’s issue:

Why it’s so hard to compare overweight and obesity rates across countries

The rising share of ministers with an economics or business degree

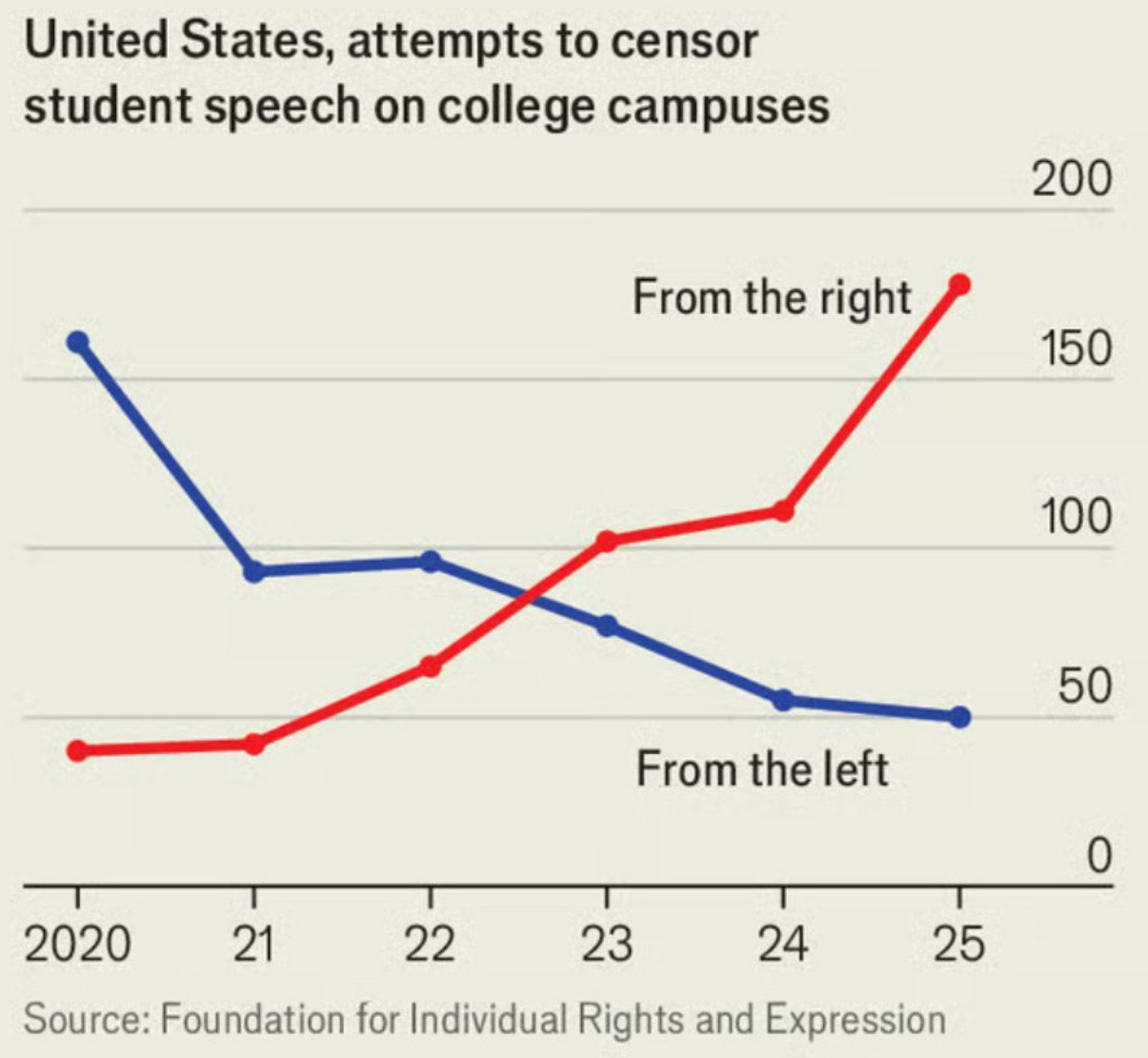

Most censorship of American student speech now comes from the right

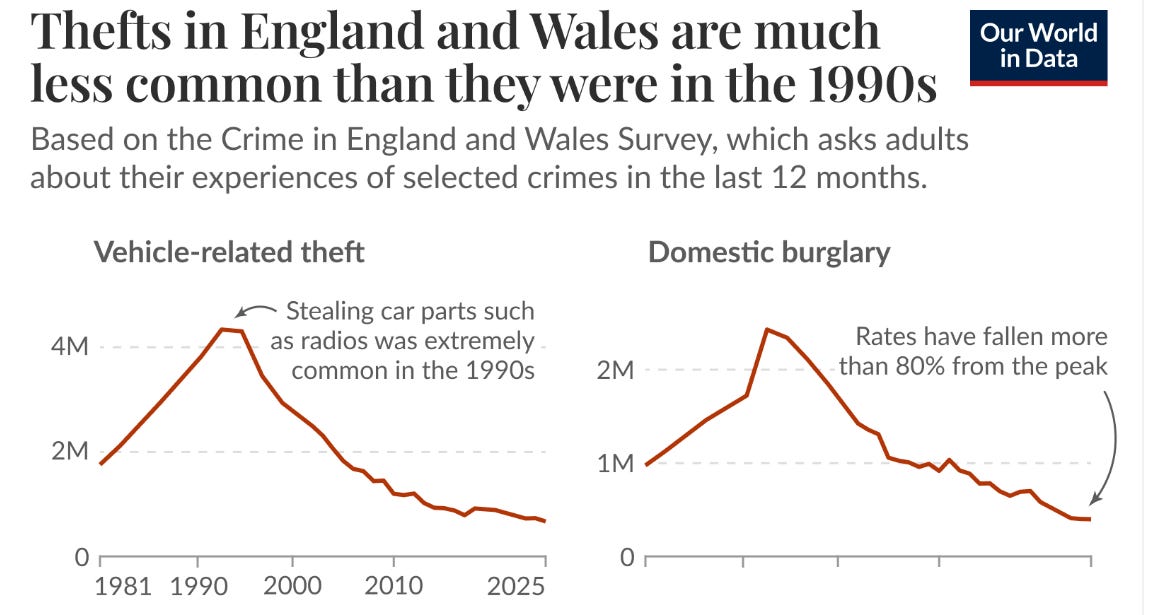

Burglaries have fallen more than 80 percent in England and Wales

Just the links: METR on faster AI progress, odds Trump won’t finish, and more

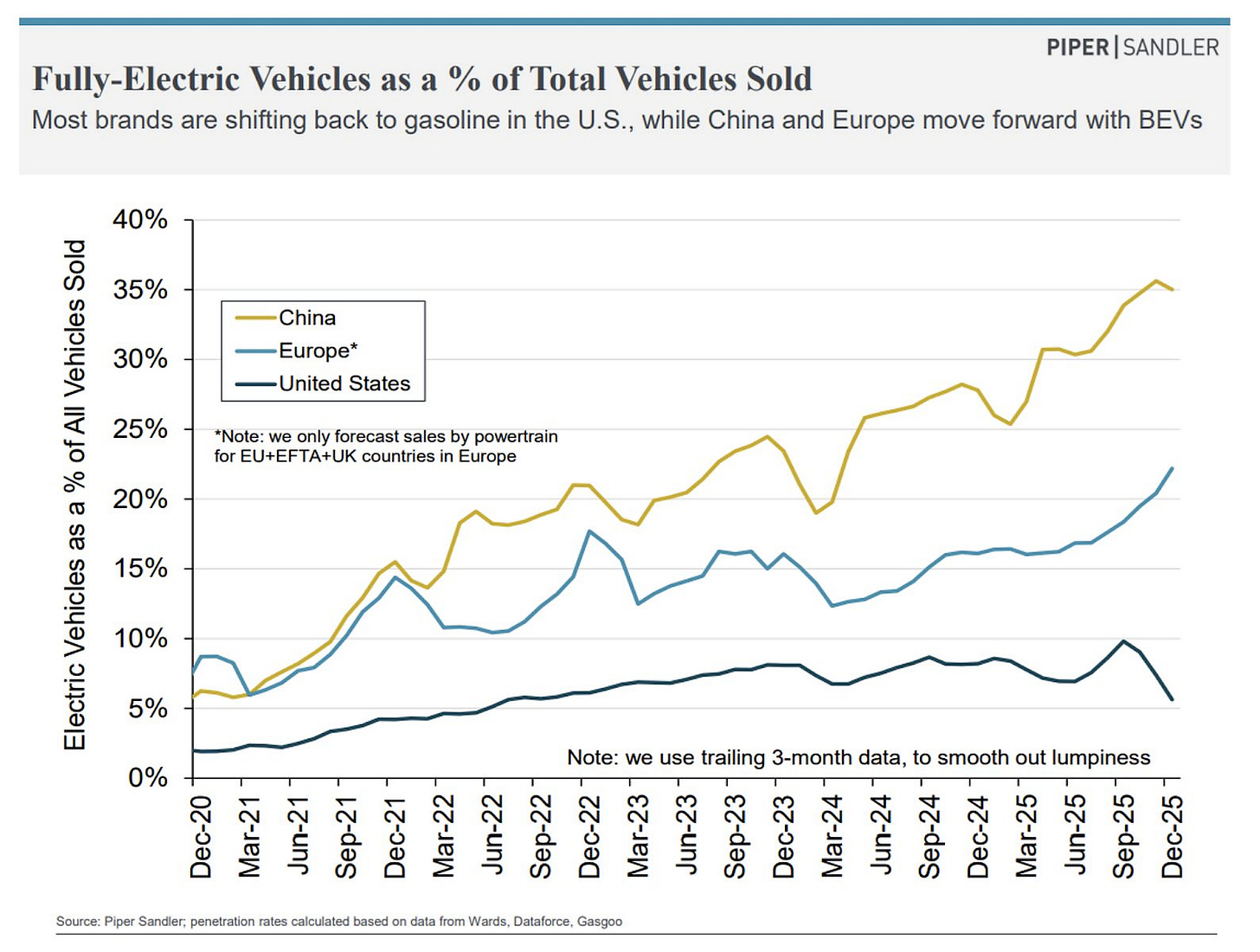

The growing EV split between China and the US

Sales of electric vehicles (EVs) in the US have fallen to levels last seen in 2022, likely in part because federal tax credits have been scrapped. By contrast, EV sales continue to surge in China, supported by continued tax breaks.

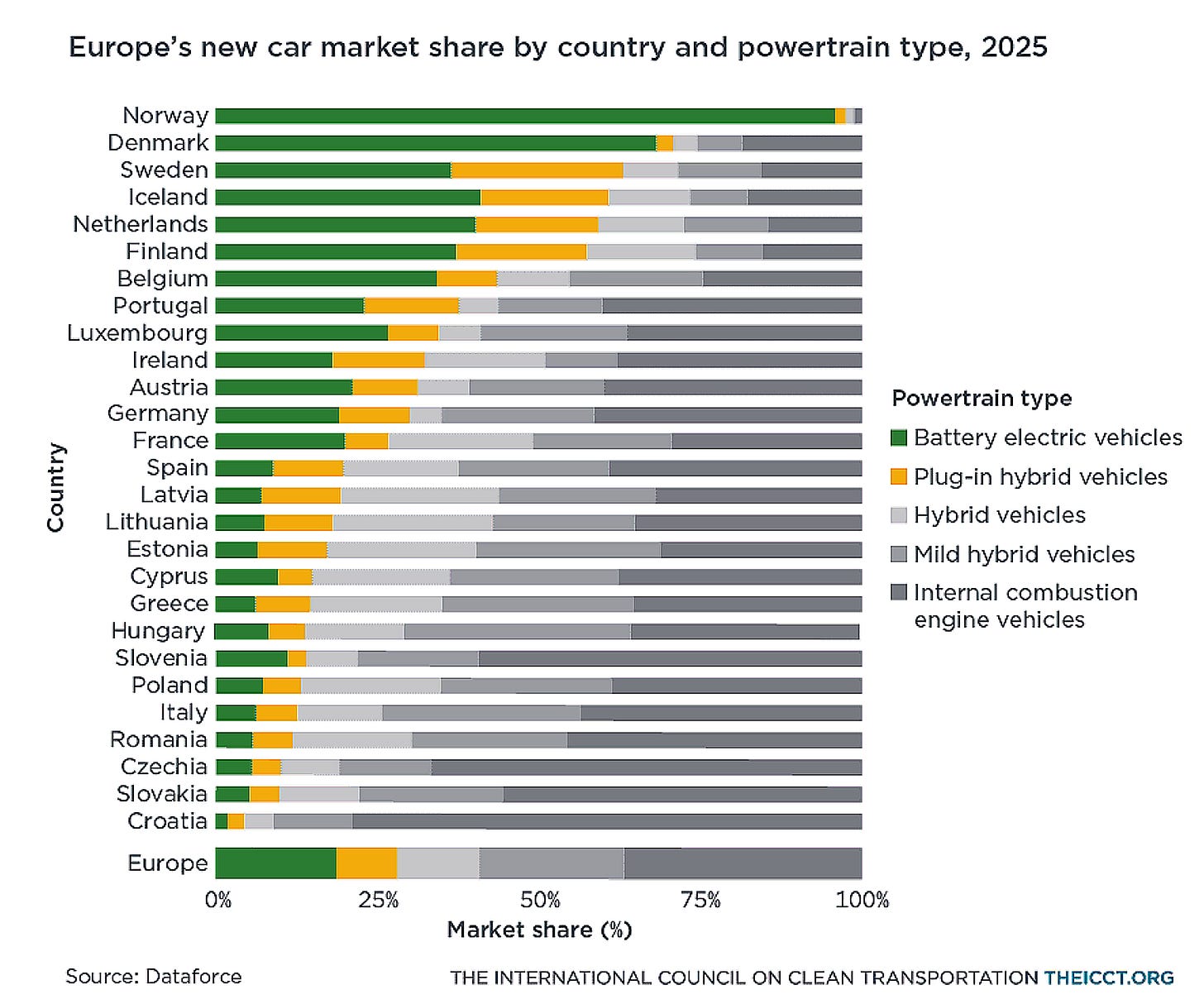

Europe sits in between, but the aggregate figure masks huge variation: from nearly complete EV adoption in Norway to almost none in Croatia.

Why it’s so hard to compare overweight and obesity rates across countries

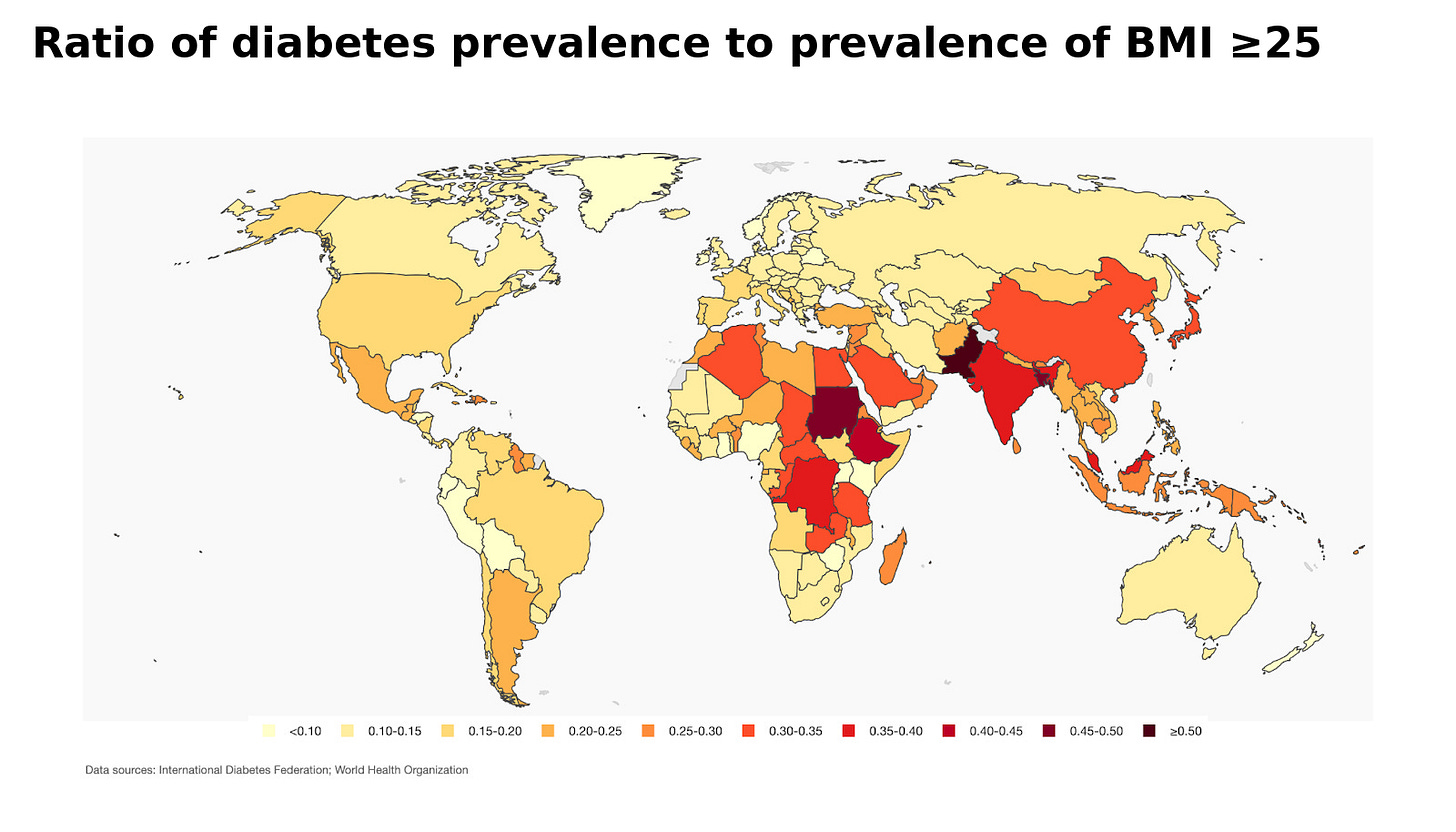

What does it mean to be overweight? A common definition says that you’re overweight if your body mass index (BMI) – the ratio of your weight to your height squared – is at least 25. But as Hannah Ritchie notes, a problem with this definition is that the health risks of having a BMI of 25 are very different in different populations. Consider this map comparing estimates of diabetes prevalence to estimates of how common it is to have a BMI of at least 25.

Adapted from Hannah Ritchie (title changed).

The variation in health risks has led the UK to lower the threshold for overweight for certain groups. Official health advice sets it at 23 for people of Asian, Middle Eastern, Black African, or African-Caribbean background.

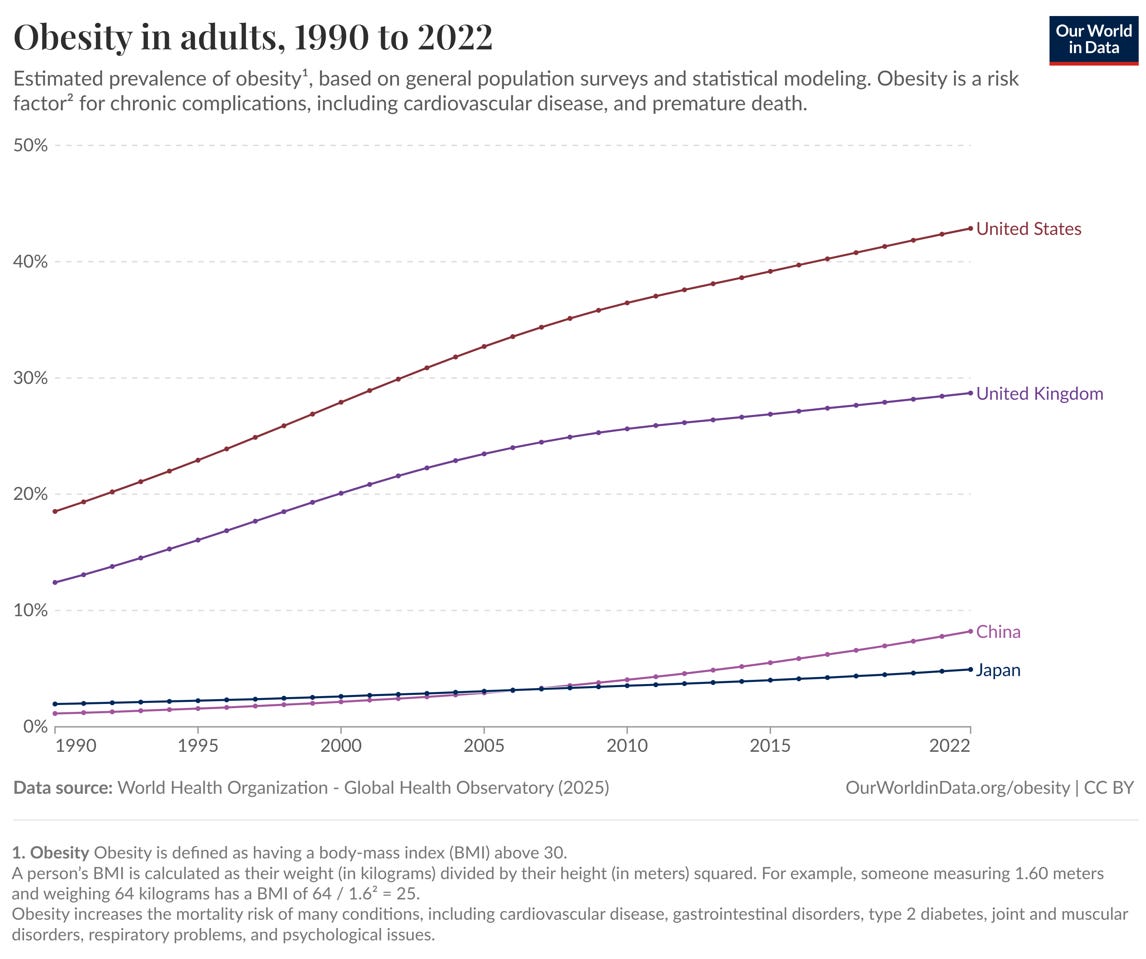

People making international comparisons of overweight and obesity rates often fail to appreciate these differences. They share charts showing extremely low obesity rates in East Asia, not realizing that this assumes the standard cutoff of 30, which is probably too high for those countries. We need different cutoffs for different countries, and that makes it difficult to compare them.

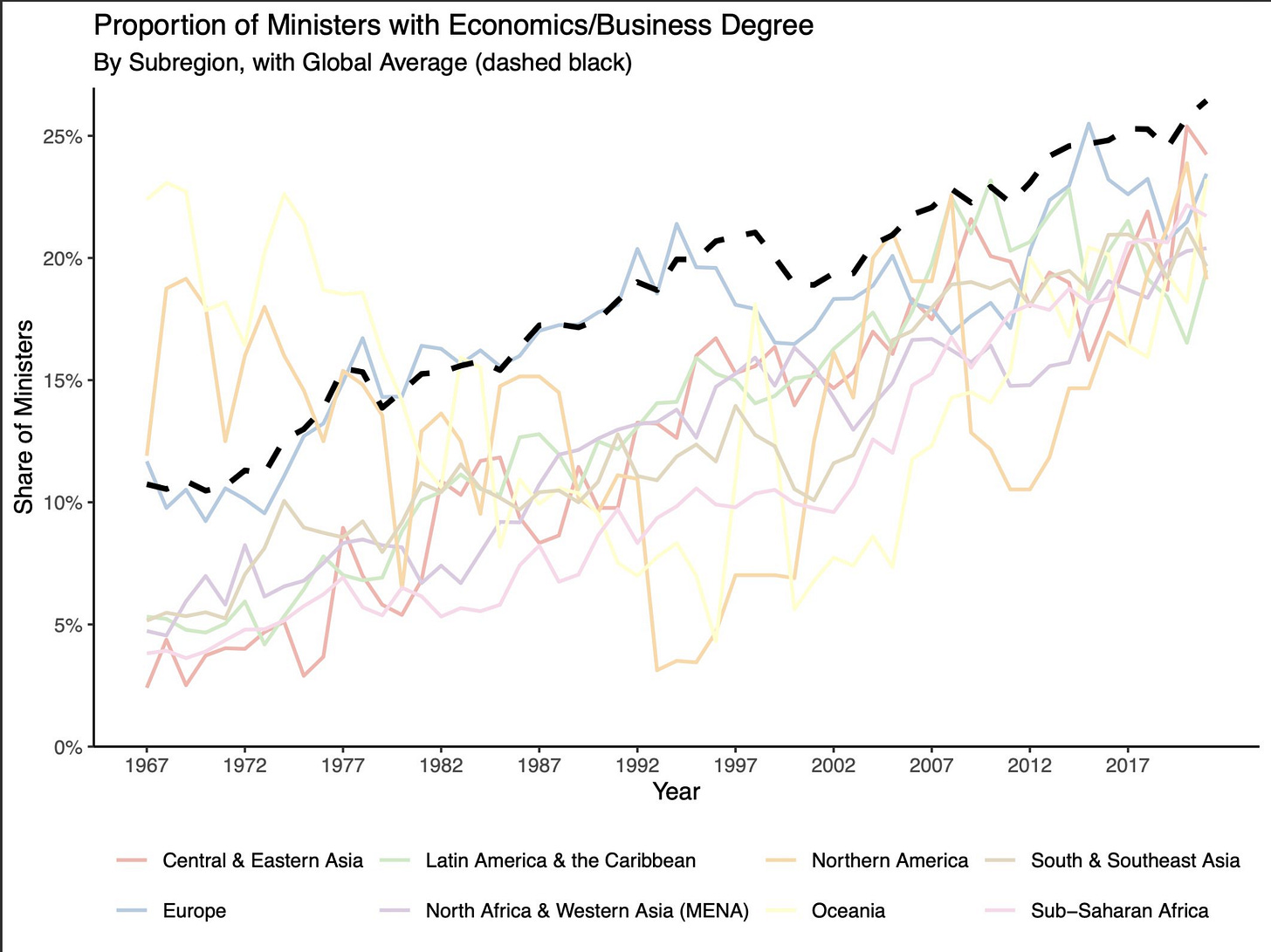

The rising share of ministers with an economics or business degree

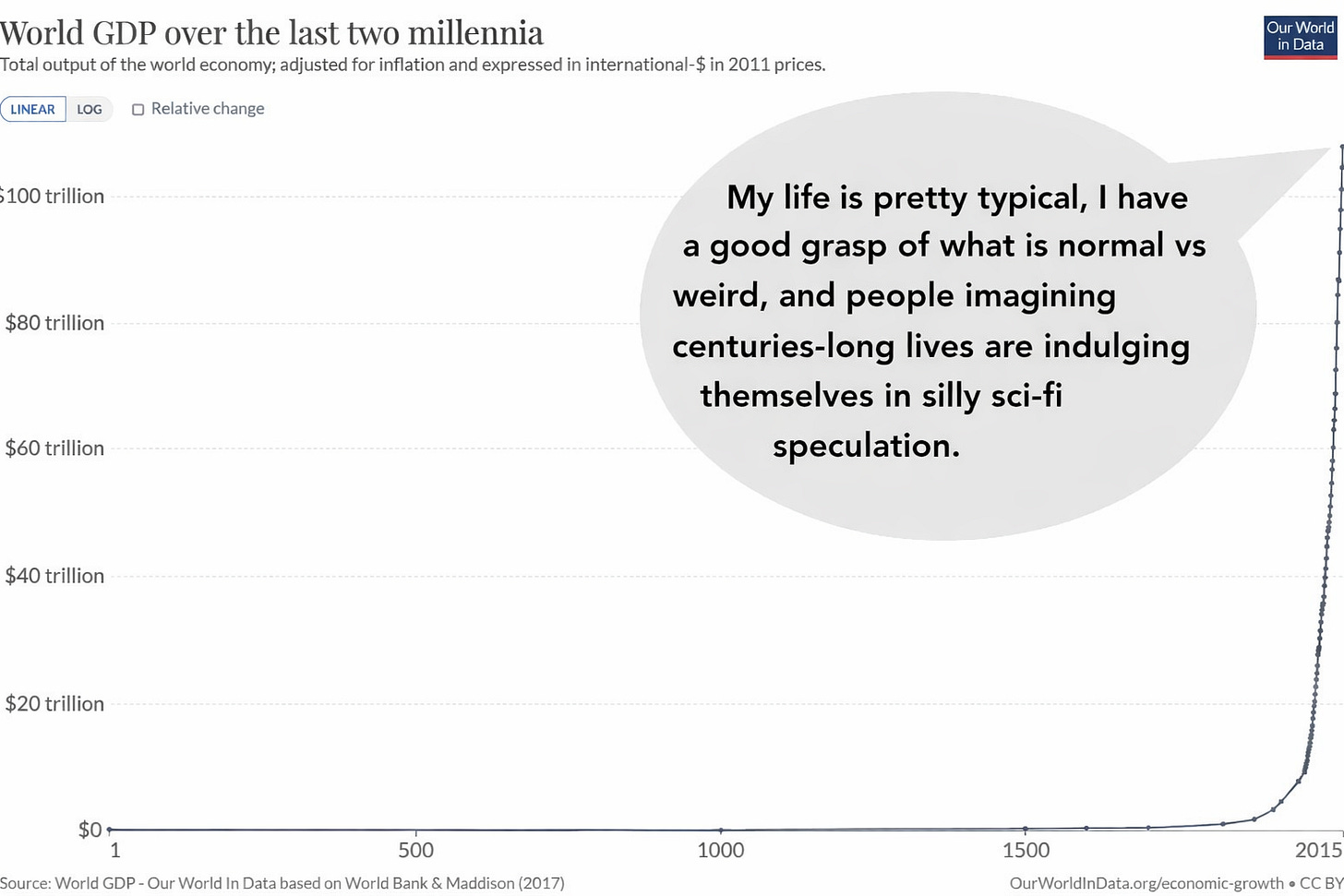

Why we shouldn’t accept death, as a civilization

Many people are skeptical of attempts to increase the human lifespan, but the arguments aren’t always very clear. In the Financial Times, Jemima Kelly argues that these attempts ‘reveal a self-centred society that has become detached from community, and one that struggles to accept mortality and the fact that when we die is not something we can control, and is largely down to our genes’. How should we understand this?

One argument Jemima makes is that many of those who try to extend their lifespans are self-centered. But even if we were to concede that, it doesn’t follow that longevity isn’t a valuable goal. The character of people who pursue a goal is distinct from whether it’s worth pursuing.

Her other argument is that we should accept that we can’t overcome our mortality – perhaps to keep our peace of mind. It’s true that it may be wise for people who are now old to prepare to die, since that’s the likely outcome. But I think we should take a different approach when we consider longer time frames. It doesn’t seem implausible to me that we could drastically increase human lifespans at some point. Even if it wouldn’t happen very soon, it would still be worth pursuing for the sake of our descendants.

Adapted from Rob Wiblin.

Most censorship of American student speech now comes from the right

AI productivity gains may be smaller than studies suggest

What is the impact of AI on productivity? There are lots of studies being thrown around – often to push a specific narrative – and it can be hard to orient yourself. Now economist Alex Imas has published a useful overview of the evidence (which he’ll keep updating). He distinguishes between micro studies – controlled experiments on specific tasks or jobs – and macro studies, which use aggregate productivity statistics. Each category has its own strengths and limitations. The micro studies are precise but narrow: they can estimate how much AI increases productivity reasonably well, but only for the tasks or jobs they study. The macro studies have the opposite problem: while they look at broad productivity changes, they have trouble determining how much is due to AI.

The micro studies typically find that AI has moderate productivity benefits and that it has an equalizing effect, disproportionately helping less skilled workers. But I think we should be careful about generalizing their findings to the wider economy. The productivity gains may in part be due to researchers selecting tasks where AI is likely to help, as the macro data don’t show similar gains. And as Alex points out, the equalizing effect may stem from the micro studies holding AI adoption fixed by design, to isolate the productivity impact of particular uses of AI. Once you factor in that higher-skilled workers use AI more, the effect might disappear or reverse. These types of generalizability problems are underappreciated throughout academia.

Burglaries have fallen more than 80 percent in England and Wales

See also my note on similar drops in the US.

Just the links

‘Evolutionary psychology hypotheses are testable and falsifiable’

Kalshi estimates a 42 percent chance Trump won’t finish his term

Epoch podcast with Daniel Litt on how AI is uneven within math, too

Liv Boeree interviews Will MacAskill on the future with superintelligent AI

The lexical fallacy: disregarding all other policy criteria for the sake of one

Toby Ord on compute costs and how they may increasingly impede AI usage

EU launches Starlink alternative to avoid relying on US tech

Relatedly, France bans officials from using US video tools like Zoom

That’s all for today. If you like The Update, please subscribe and share with your friends.

People really cling to the idea that excessive fat = weight, so any measure of fat that isn't based on weight is dismissed. There is a far better alternative to BMI and that is waist-to-height ratio, but medical researchers, governments, and the public consistently reject it.

I personally think we have to look at EV sales for each country based upon that country's preferences, resources, and economics. For Americans with abundant and cheap oil, EVs don't represent the same value and benefit as you see in the EU and China, which have virtually no oil. In China, they also don't care as much about a green energy stack, so most of the electricity is generated by coal, so in essence, the EV is the best alternative given their energy resources, coal, which they use to generate electricity. I recently posted on why we should allow Chinese EVs into the US, as a response to Noahpinion's post on the same topic. I think Americans have much more range anxiety than people in other countries because we drive so much more and such longer distances than in the EU and China. I am waiting to purchase an EV until the range is 1,000 miles and charging times are less than 15 minutes. I think we may get there in five years, so that is when I plan to purchase an EV.

https://chriswasden.substack.com/p/the-creative-response-to-chinese?r=2tf1q