How postponed births soften the fertility fall

Plus: the economic recovery after Covid, big business growing its market share, and more

Welcome to The Update. In today’s issue:

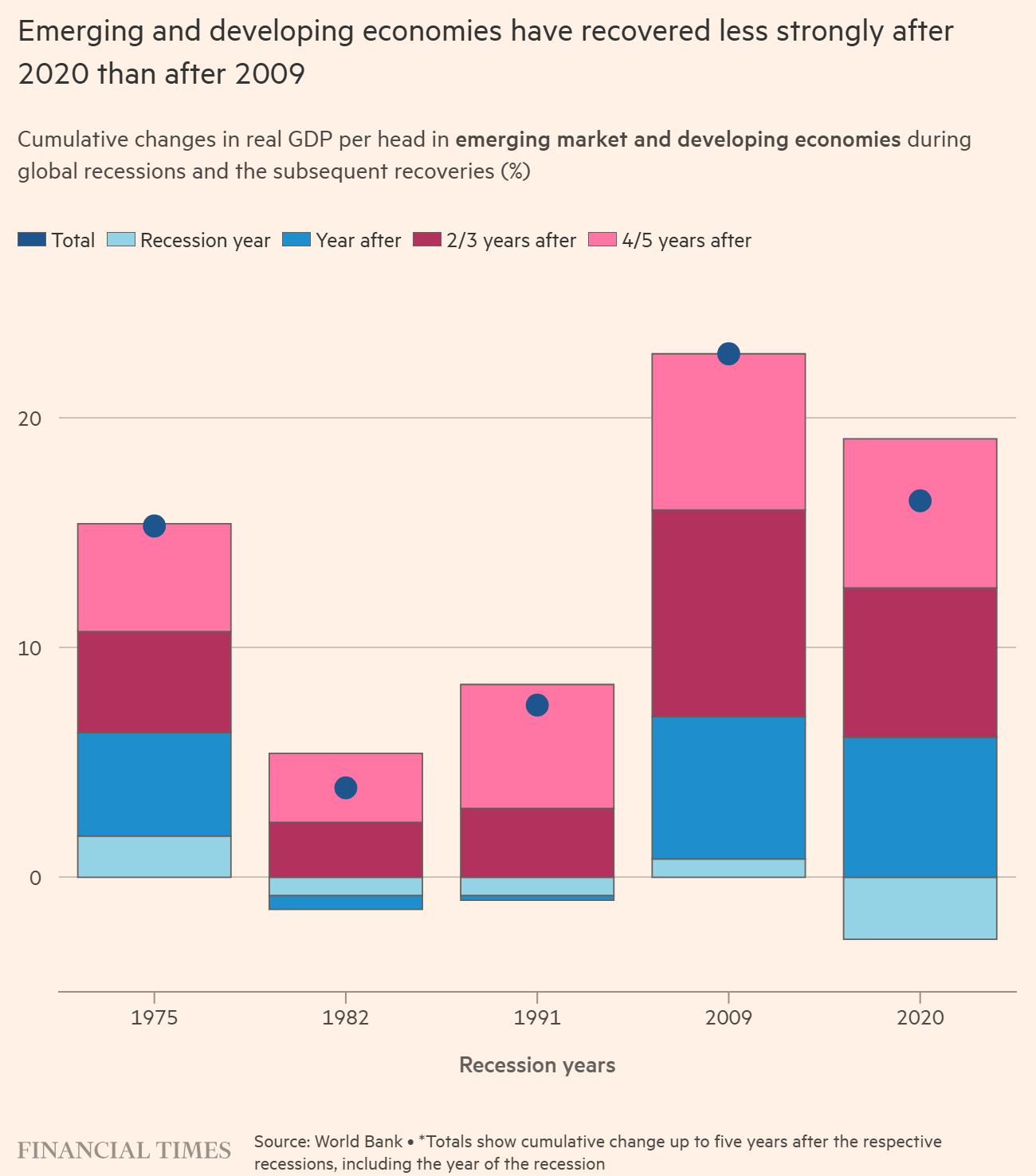

Emerging and developing economies have had a weak recovery after Covid

Big business has increased its market share for more than a hundred years

Old-age spending is outpacing everything else in Western Europe

In brief: a summer program in medicine and a new article on how to shape the long-term future

How postponed births soften the fertility fall

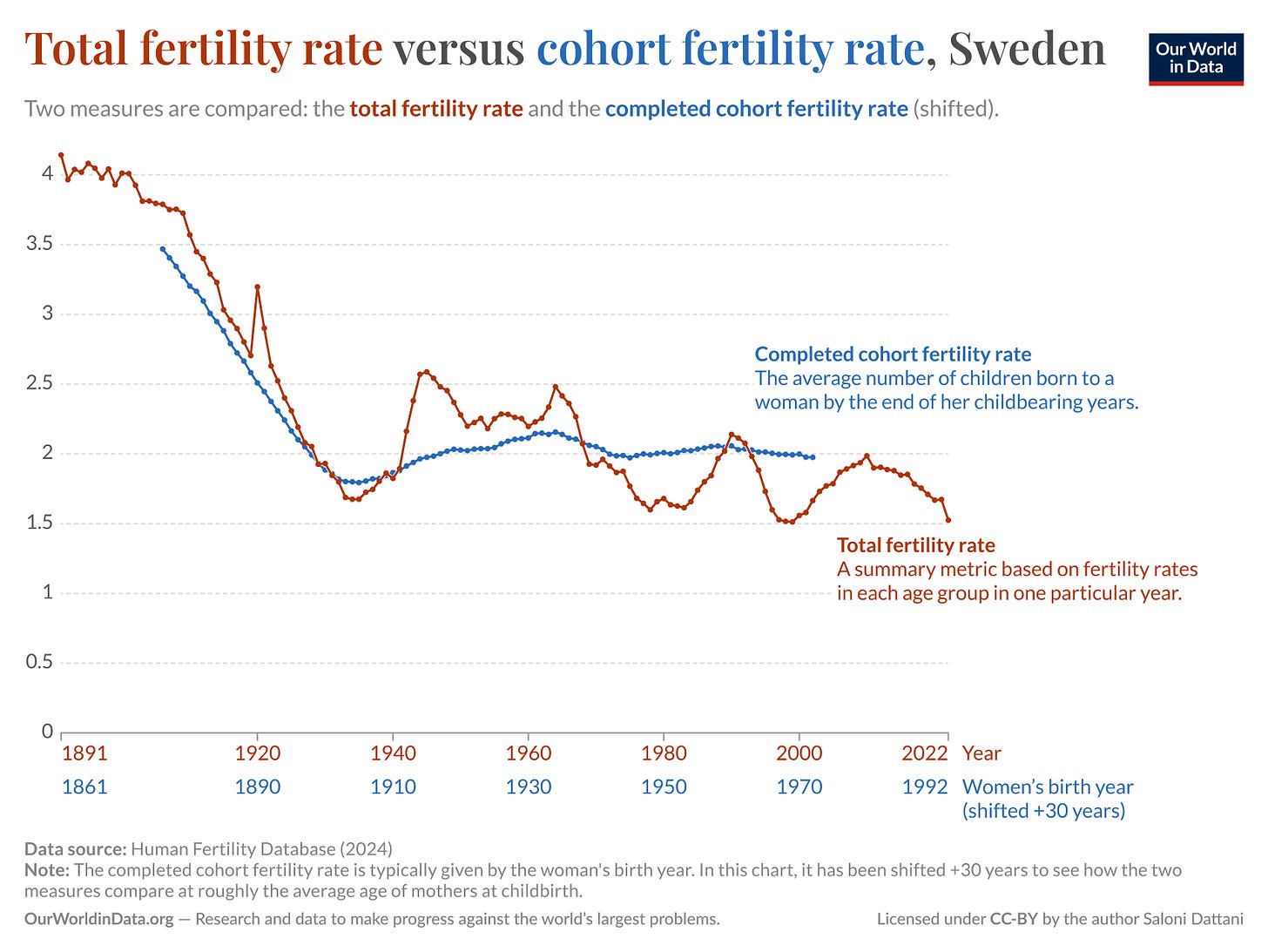

Much of the reporting on falling fertility focuses on the total period fertility rate – a measure based on the number of births in a particular year, like 2025. But what matters most is the completed cohort fertility rate: the number of children women born in a particular year – say 1970 – have had by the end of their childbearing years. And period measures can sometimes give a misleading impression of what the completed cohort fertility rate is going to be. When women postpone childbearing while ultimately ending up with the same number of children, period fertility will still temporarily fall. Here’s an illustration of how the two measures can diverge.

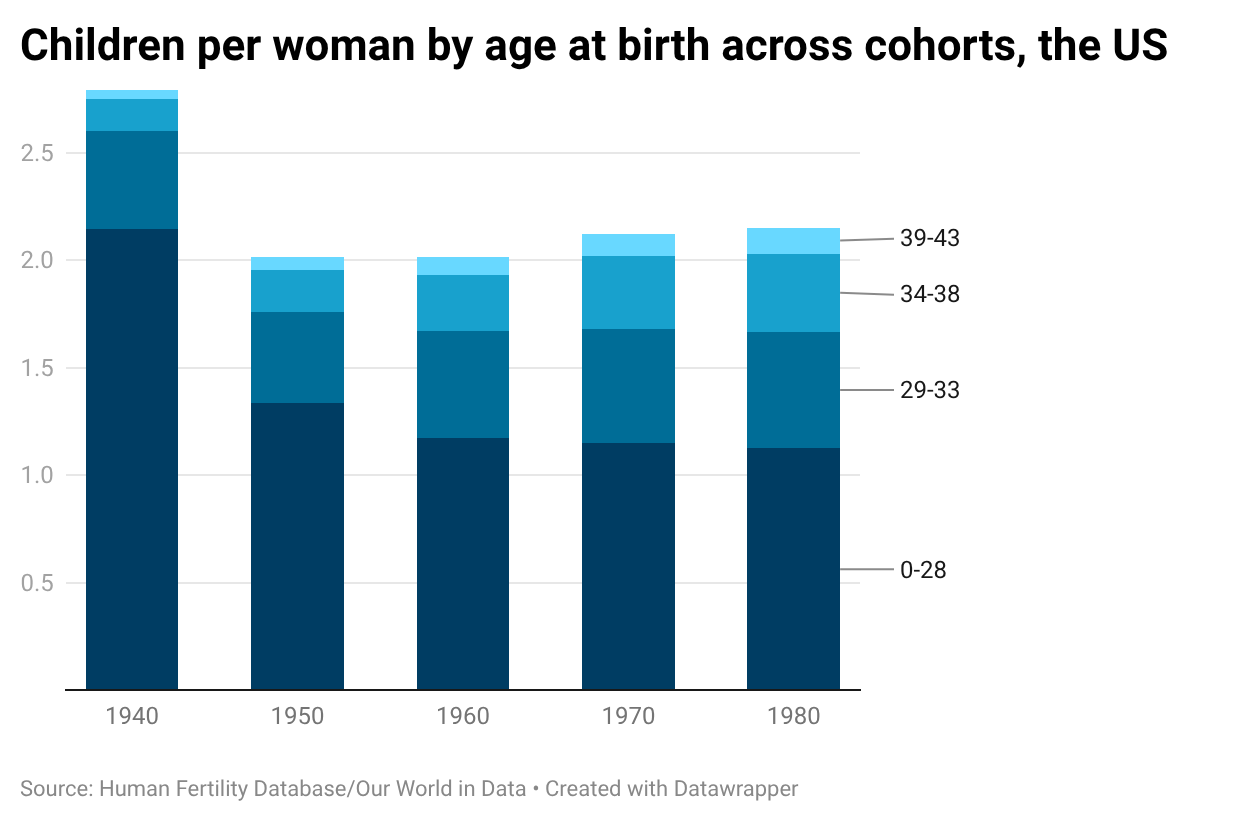

So, is fertility not declining but merely delayed? For American women born around 1980 or earlier, that is indeed the case. Across the 1950–1980 cohorts, women kept having fewer children at a young age – but this was more than made up for by more births later. By age 43, the 1980 cohort had a higher fertility rate than the 1950, 1960, and 1970 cohorts. (While this isn’t quite the completed cohort fertility rate – women do have children after 43, after all – that’s too rare to substantially change the picture.)

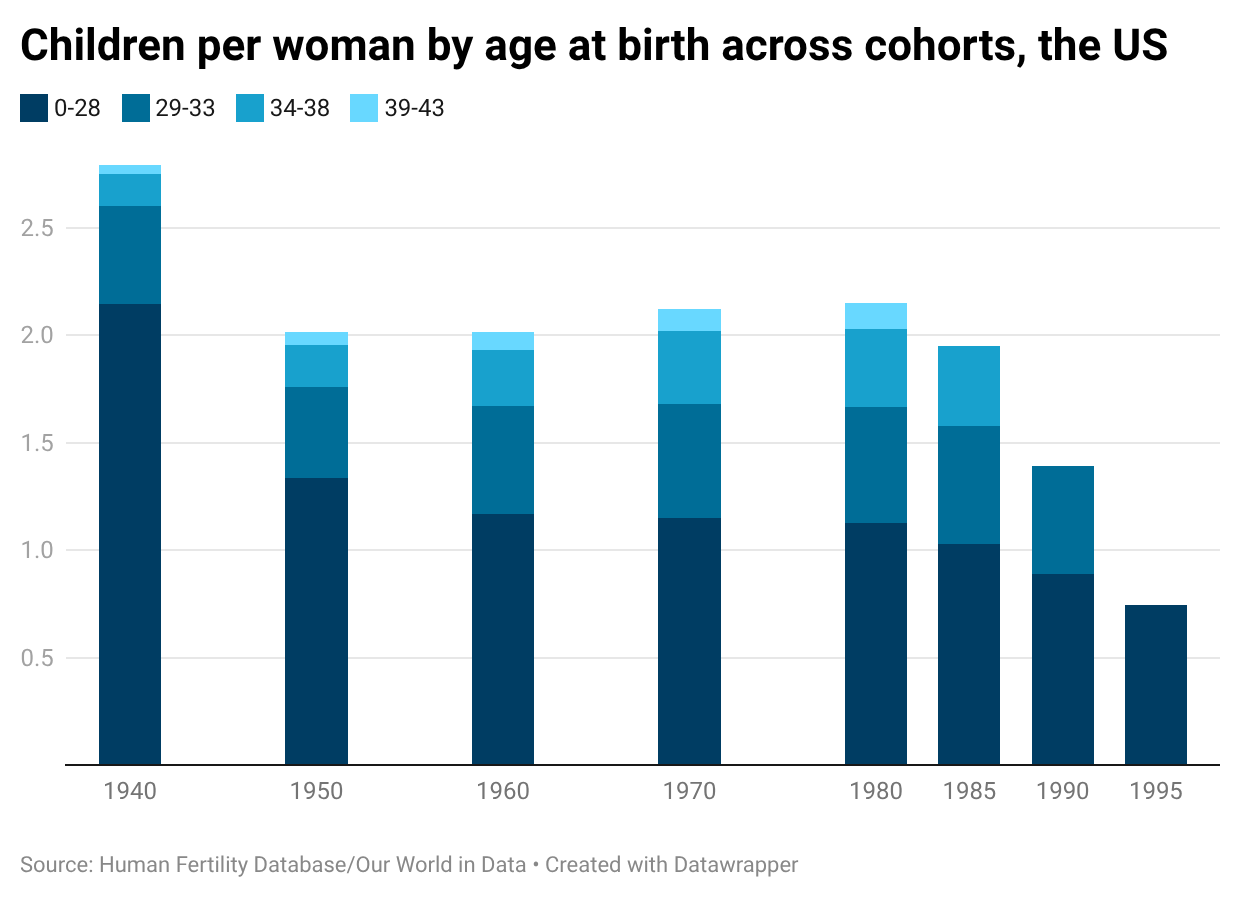

As we can see, the fertility rate among women born in 1980 exceeded the replacement rate. Will this continue to be the case? Will the declining fertility among younger women continue to be made up for by more births later on? That is starting to look less likely, since births at younger ages have fallen much more among women born in 1985, 1990, and 1995.

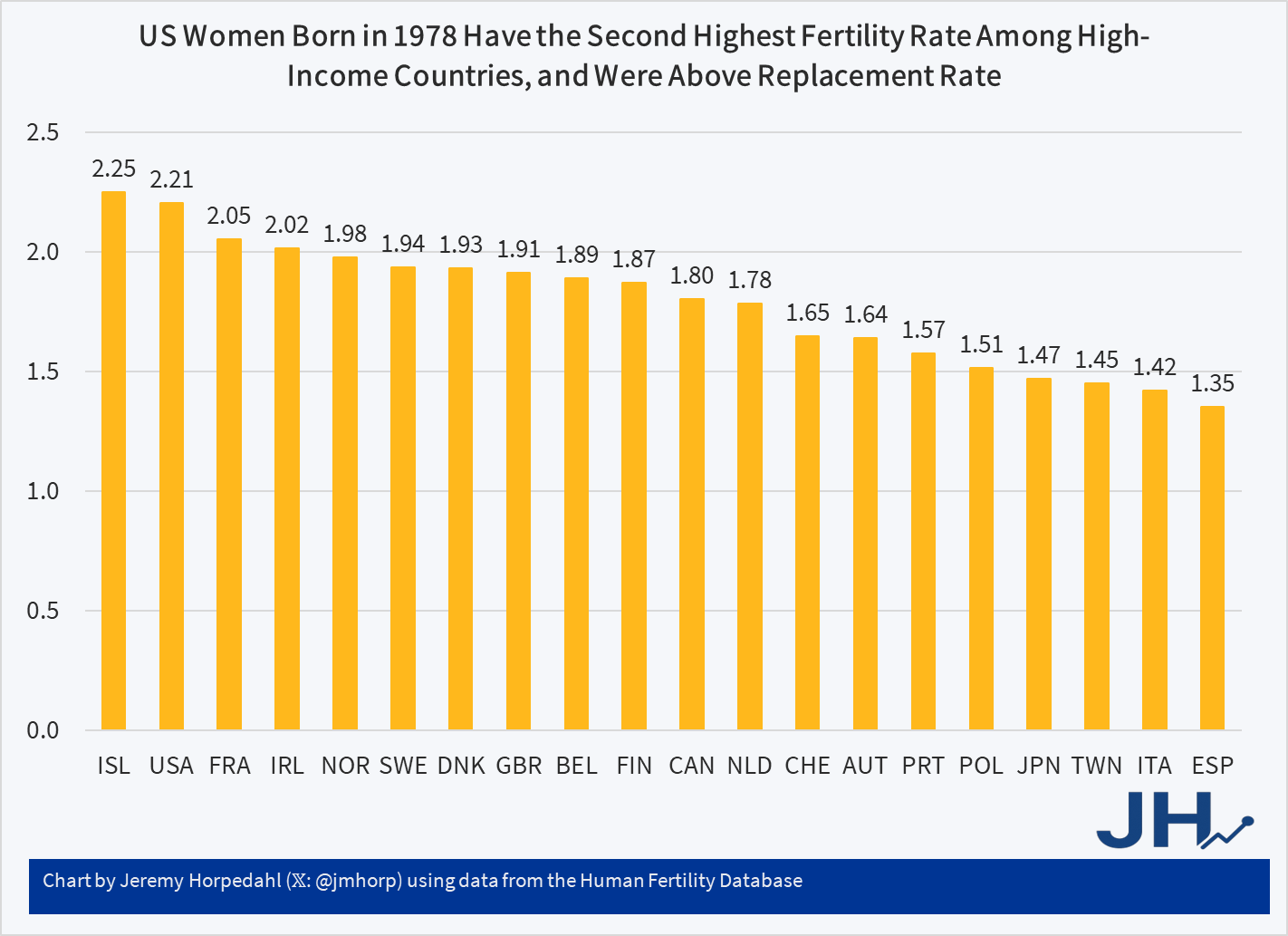

The fall in fertility is real – and let’s also remember that many other developed countries have a much lower fertility rate than the US. That said, we should pay attention to the increasing number of births at later ages, since they do soften the fall. This effect may grow even more pronounced if fertility technology improves further.

Emerging and developing economies have had a weak recovery after Covid

After the Great Financial Crisis of 2008–2009, emerging and developing economies enjoyed a much stronger recovery than advanced economies. But they’ve not done particularly well after Covid, as Martin Wolf shows in the Financial Times.

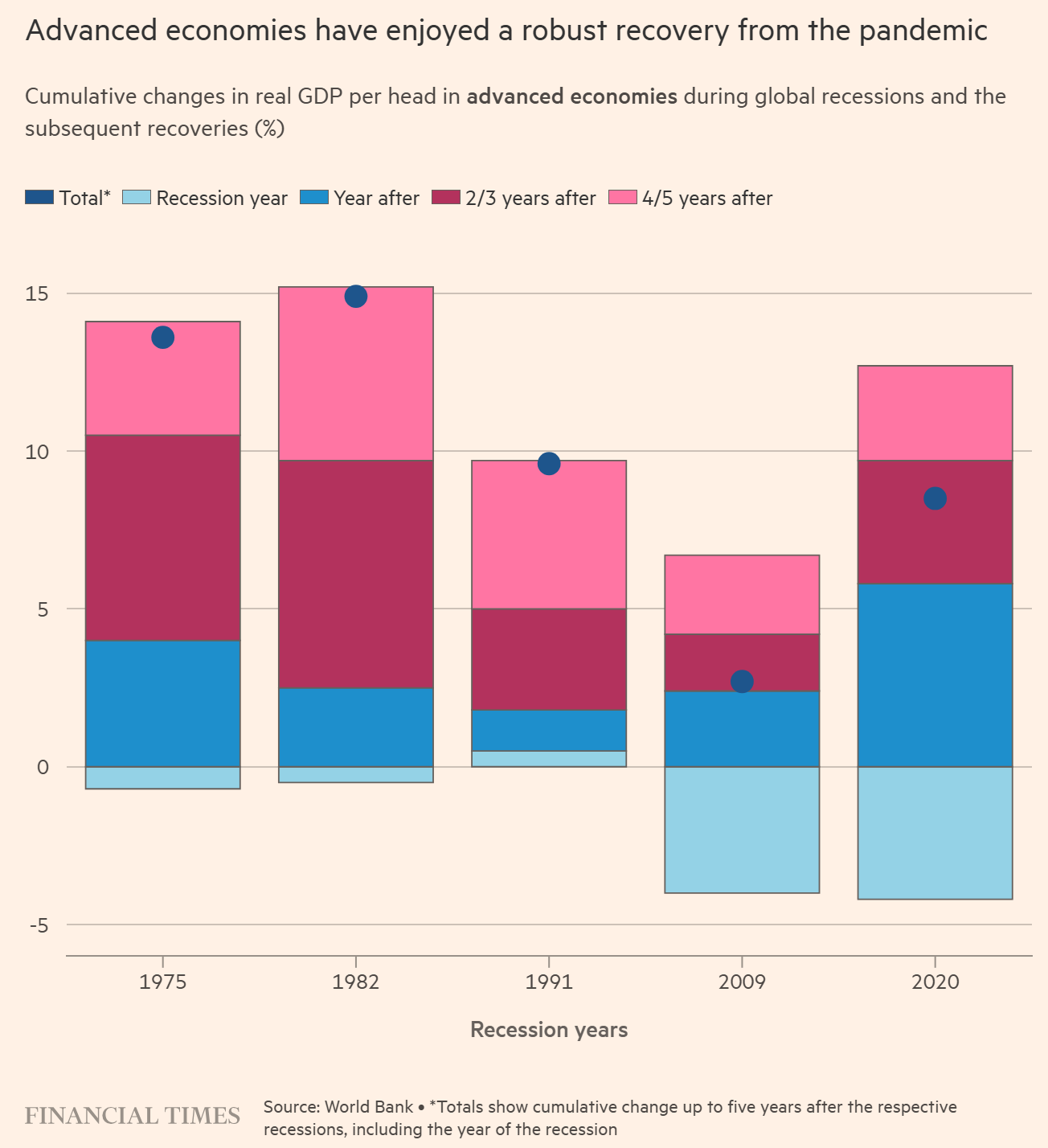

By contrast, advanced economies have done better than after the Great Financial Crisis.

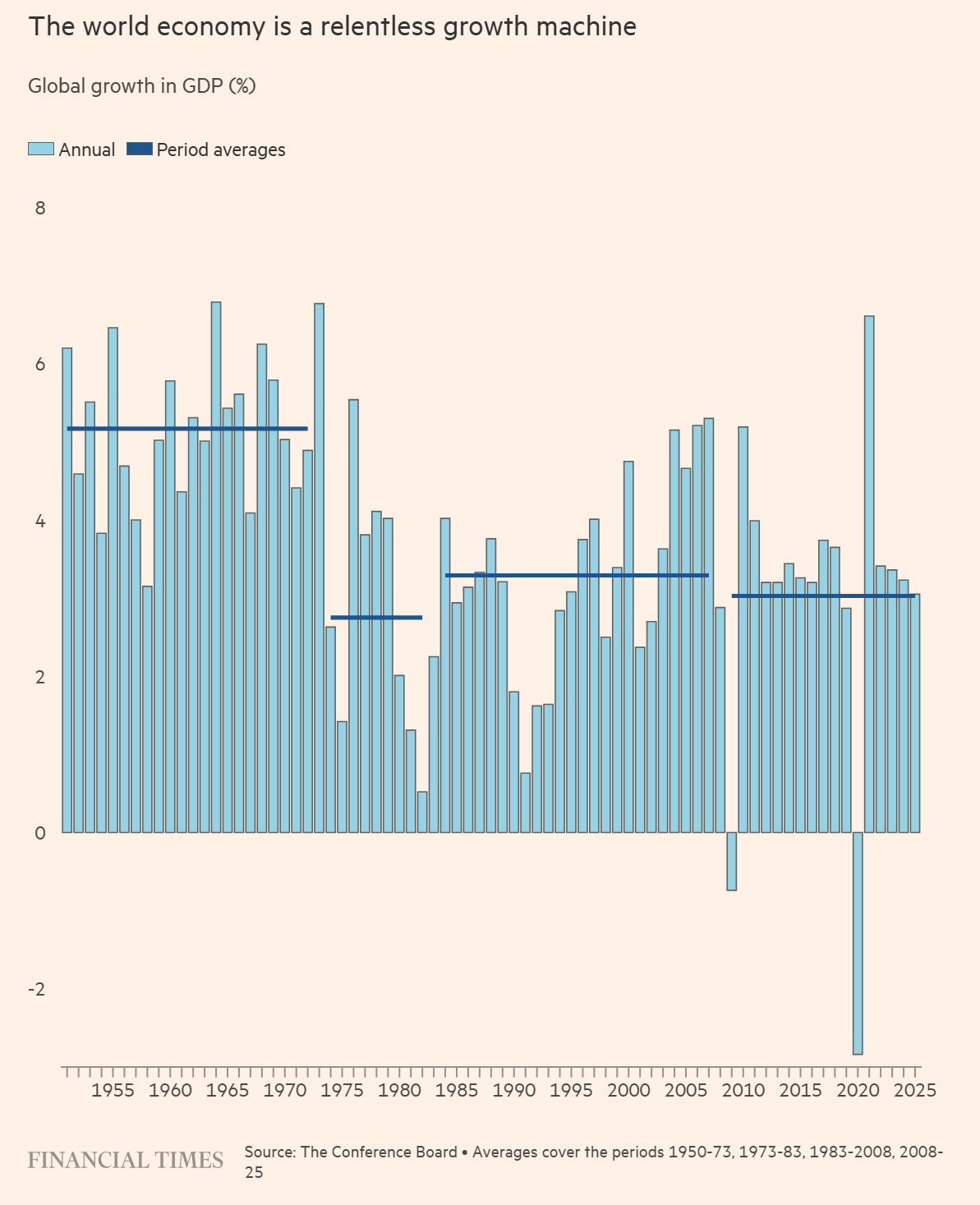

The world economy as a whole has, however, seen relative stability over time. The 2020 drop and 2021 recovery stand out, but the larger story is that growth continues roughly at the pre-Covid pace.

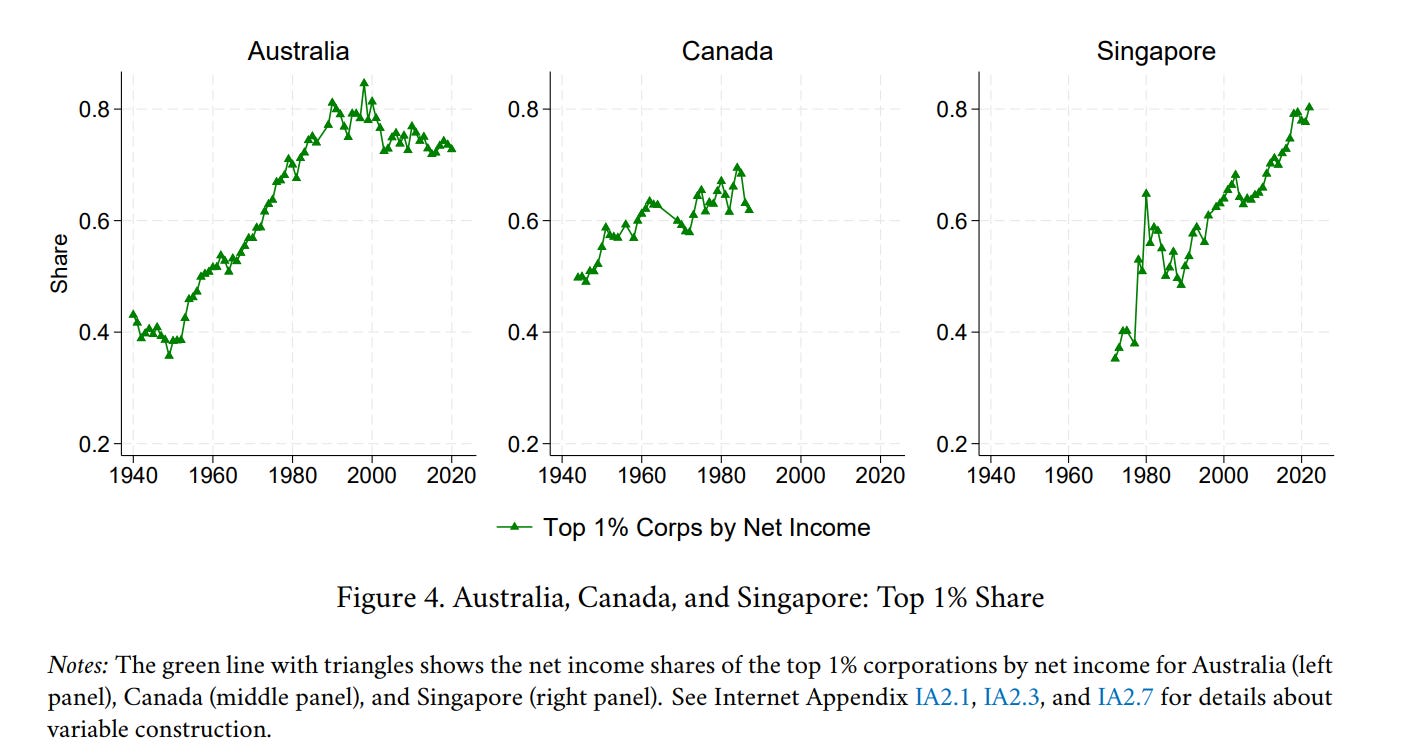

Big business has increased its market share for more than a hundred years

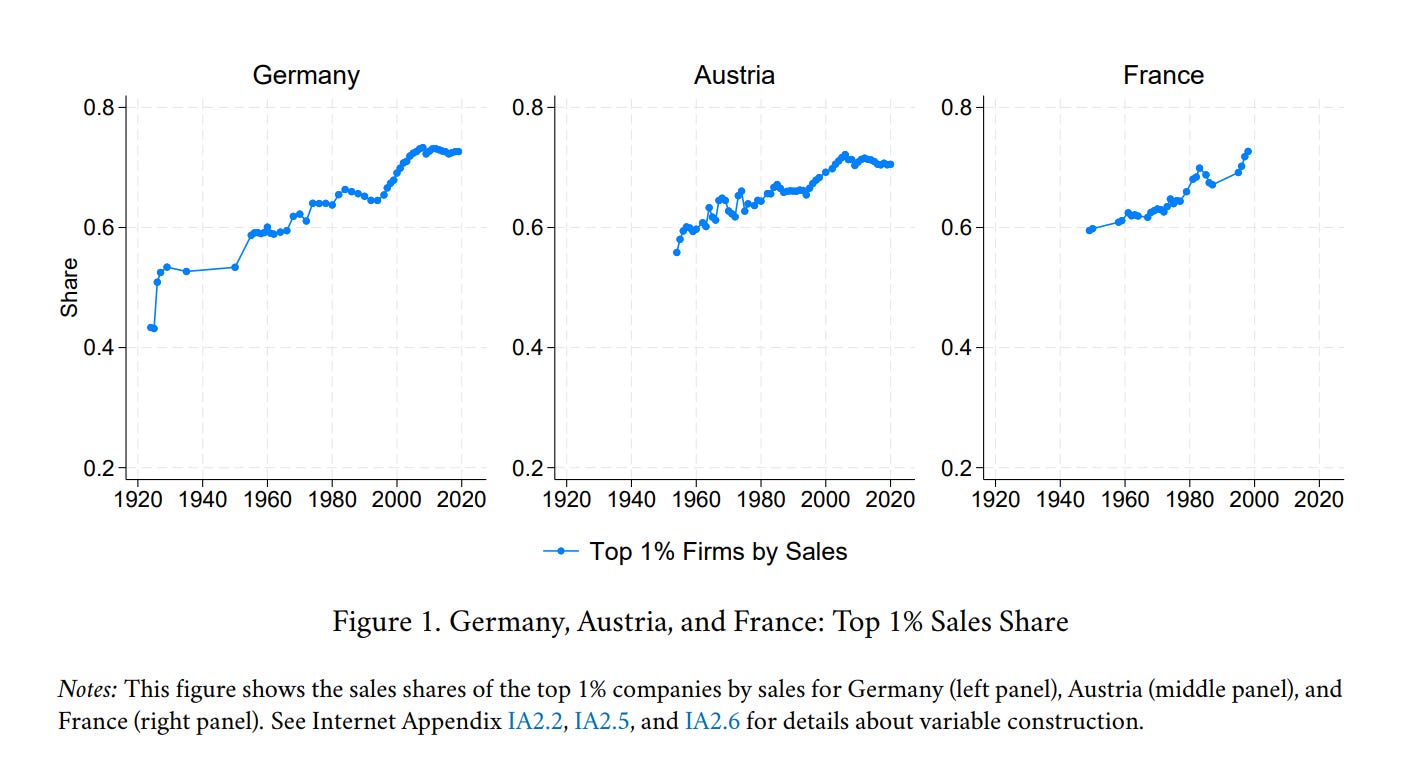

A new economics paper shows that the largest firms have steadily taken a larger market share across the rich world since 1900. While previous research had demonstrated this pattern for the US, this article shows that it’s not country-specific, but seems to be the default outcome in modern free-market economies.

A positive side of this development is that it may have increased economic growth, since big firms tend to be more productive than smaller firms.

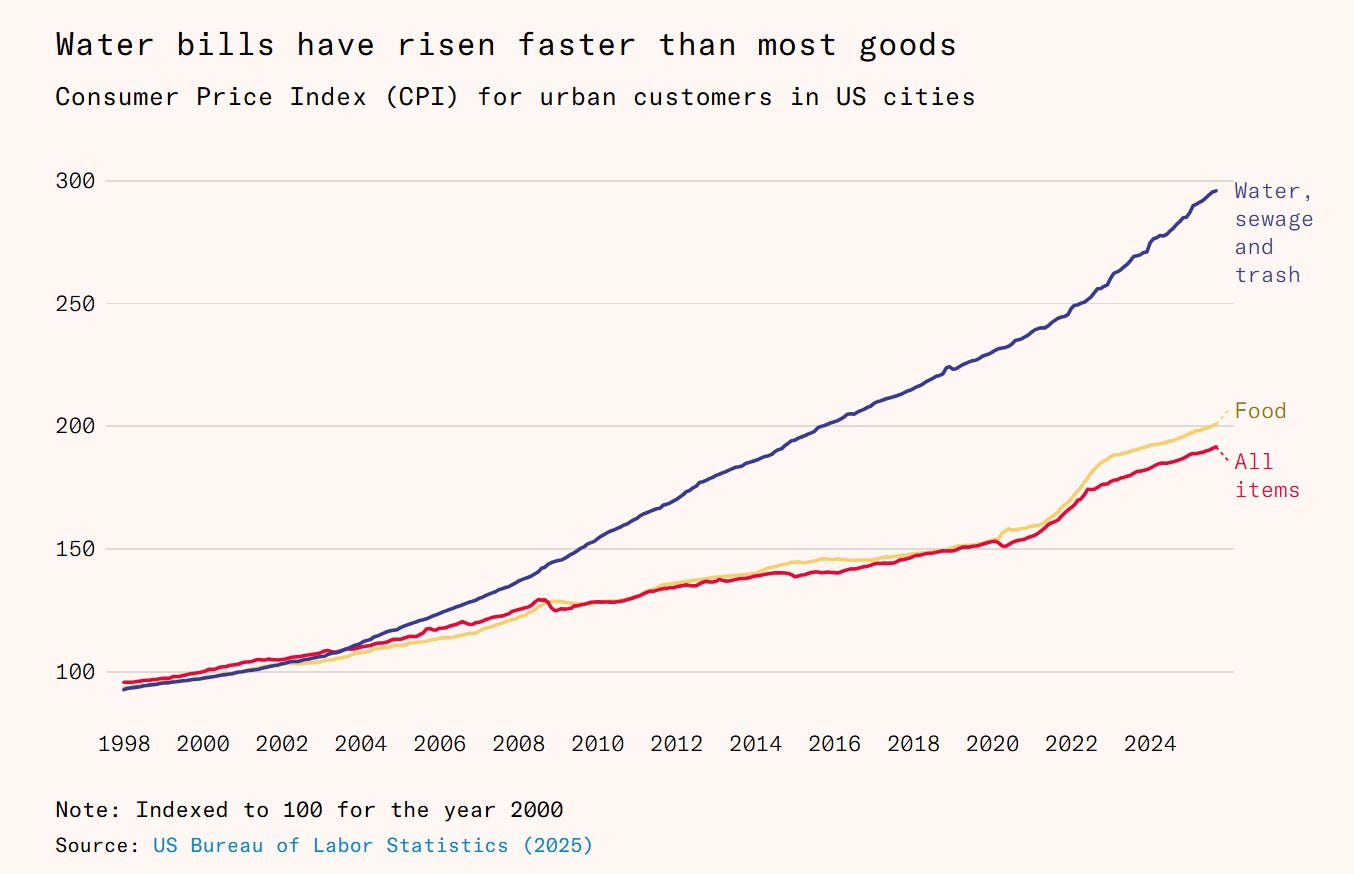

The rising cost of American water

In a new article for Works in Progress, Judge Glock shows that American water and sewer bills have more than doubled in the last 40 years, after adjusting for inflation. He argues that the root of the problem is that regulators put too much weight on small risks relative to costs – like when New York City had to build a $3.2 billion filtration plant to address two rare parasites with mild health effects. This obsession with tiny or non-existent risks unfortunately shows up in many domains, from genetically modified crops to nuclear power.

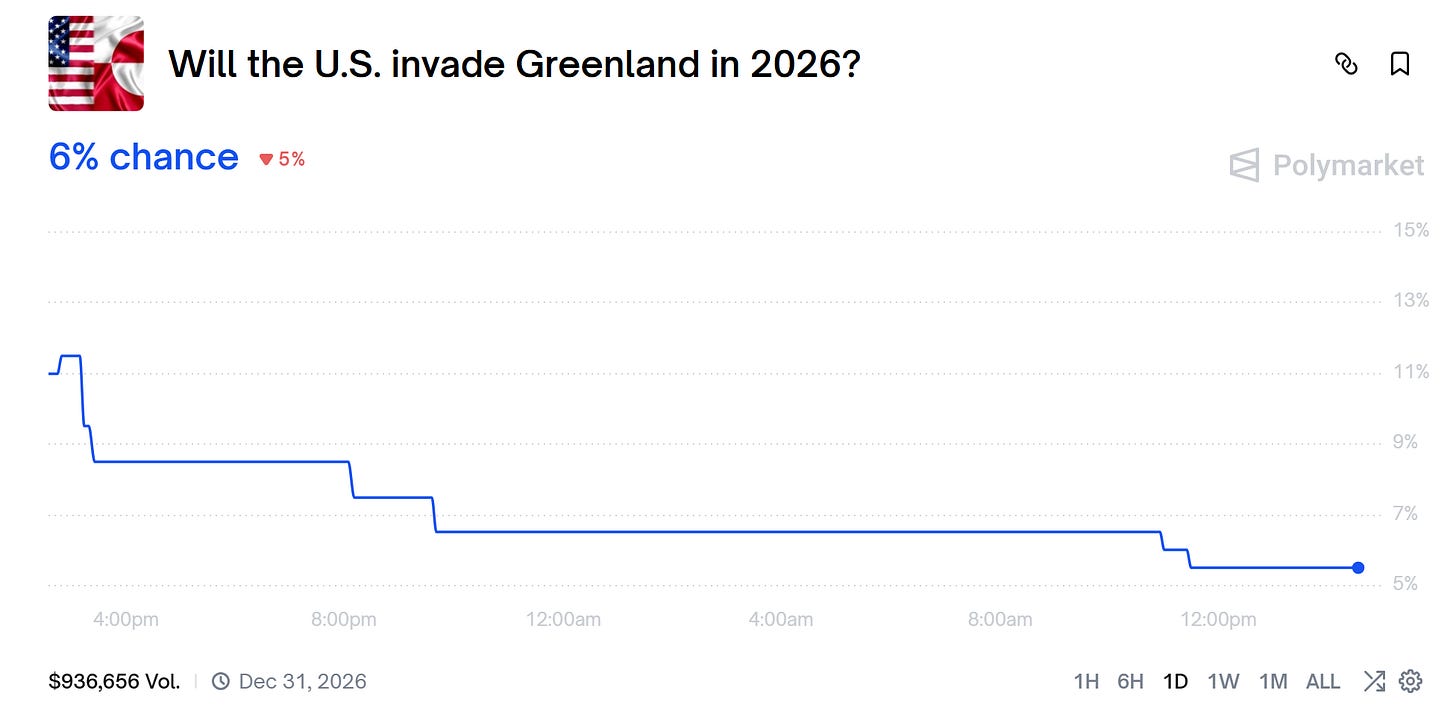

Update on Greenland

After Donald Trump said yesterday that he won’t use military force to take Greenland, Polymarket’s probability of a US invasion has halved, from 12 to 6 percent. The S&P 500 stock market index also reacted to Trump’s announcement, rising roughly one percent immediately afterward.

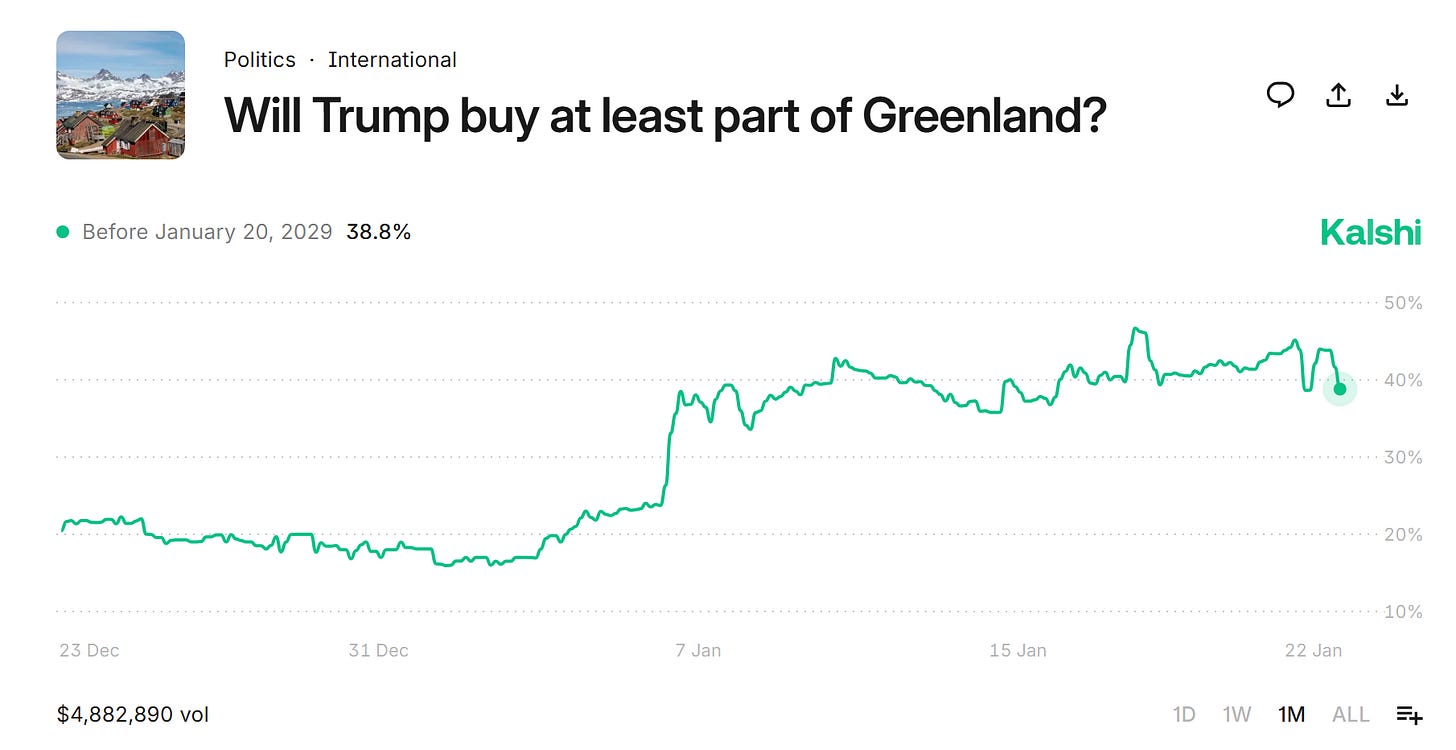

Most Greenland prediction markets have strict resolution criteria, such as full acquisition of the island. But I think it’s at least as interesting to know if there will be any border redrawing – whether small or large – during Trump’s presidency. Kalshi has a market that comes close (though it excludes forcible annexation): ‘Will Trump buy at least part of Greenland before 20th January 2029?’ It currently sits at 39 percent – a high number considering this would be an extremely rare event between NATO allies.

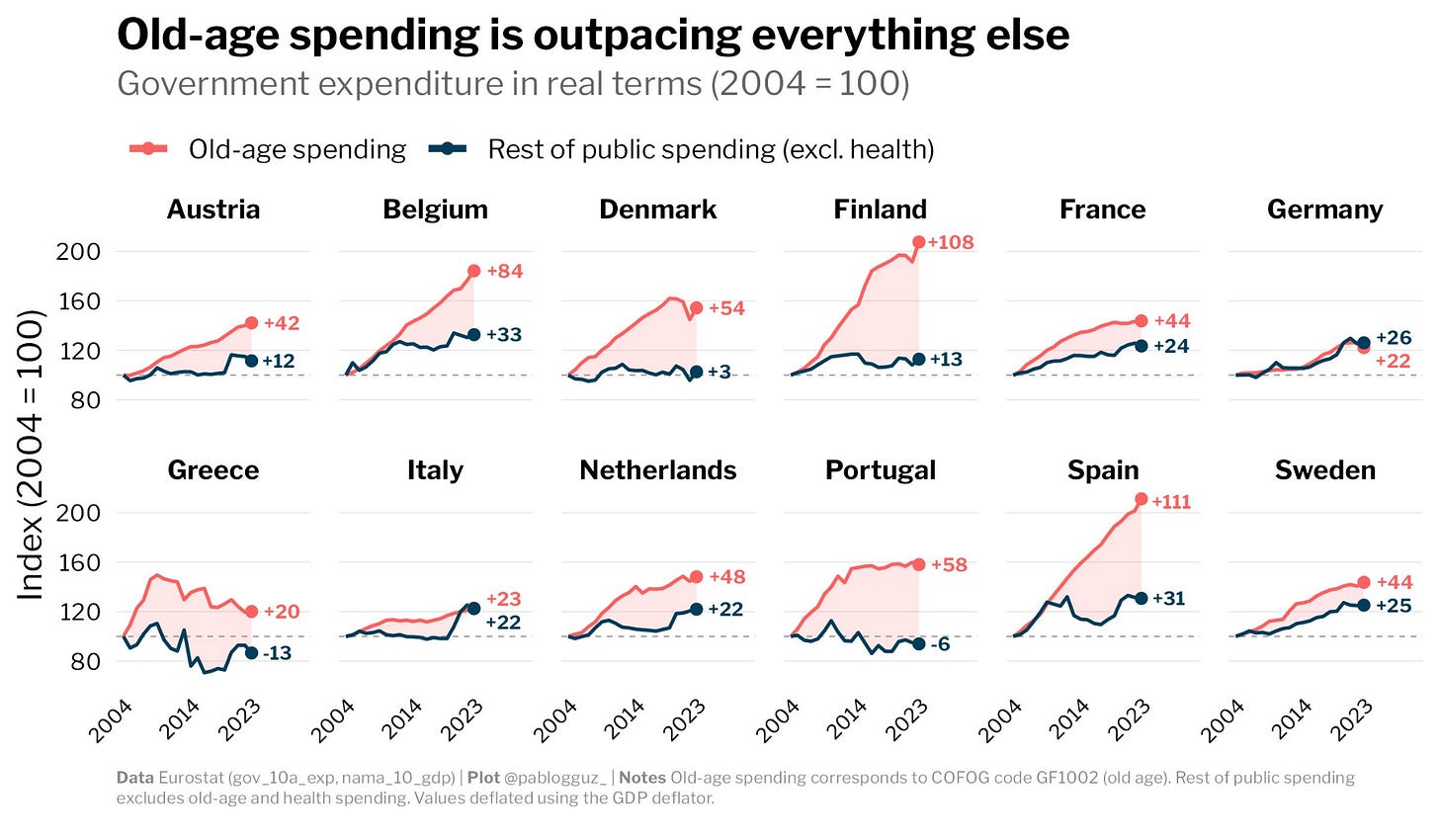

Old-age spending is outpacing everything else in Western Europe

Pablo García Guzmán has some great new charts on the rising costs of pensions and related spending on retirees in Western Europe (see also my previous article). In nearly all countries, old-age spending has grown faster than other public spending.

In brief

The Roots of Progress has announced Progress in Medicine, a summer program for high school students interested in careers in medicine, biotech, health policy, and longevity. The program runs 15th June–24th July and combines online sessions with time in residence at Stanford University, California. Priority applications (which give first consideration for financial aid) are due 8th February, and general applications are due 29th March.

How do we best shape the long-term future? Nick Bostrom has suggested that virtually all of our efforts should be spent on maximizing the chances of an ‘OK’ outcome, where we avoid human extinction and permanent civilizational collapse. But in a new article, Will MacAskill and Guive Assadi criticize this radical notion. Since we want to do better than OK, we also need to invest in projects with that aim – like programming transformative AI with values that are genuinely good.

That’s all for today. If you like The Update, please subscribe and share with your friends.

Excellent breakdown showing period vs cohort fertility divergence. The distinction between temporary postponement and permanent decline is critical for policy planning, especially when resources get allocated based on misleading period measures. Ran into this exact issue advising local health deparments where officials were panicking over short-term trends without considering delayed childbearing. The tech improvements point is interesting becauseif fertility technology advances enough, the gap between period and cohort rates could widen even further.

Once upon a time, the United States stood for opportunity, freedom, and a sense of stability. These days, though, a lot of people feel like the country’s heading off track. You see it everywhere: rising inequality, bitter political fights, social unrest, and a growing sense that you can’t really trust the big institutions that shape daily life.

Let’s talk about economic inequality first. The rich get richer while most folks are just trying to keep up, juggling higher rent, lousy paychecks, student loans, and healthcare bills that never seem to shrink. That gap eats away at people, especially younger generations who look at the future and wonder if they’ll ever catch a break or find real security.

Politics isn’t helping either. Americans seem more divided than ever, digging into their corners and pointing fingers. Instead of coming together to solve problems, everyone’s busy blaming someone else. That kind of division doesn’t just slow things down. it poisons democracy, stirs up anger, and blocks policies that might actually help.

And then there are the social issues you can’t ignore. Racism, gun violence, mental health struggles, and wild misinformation keep hurting communities. Social media just turns up the volume, spreading fear and outrage, making it harder for people to actually hear one another or find any common ground. Trust is fading not just in the government or the news, but sometimes even in the people next door.

It all takes a real toll. People are anxious, overworked, and feeling more alone than ever. Families worry about making rent, workers feel like they don’t matter, and young people wonder what kind of future they’re even working toward. The emotional weight of all this is as heavy as the financial burden.

But here’s the thing: it doesn’t have to stay this way. The United States still has some pretty incredible strengths: creativity, diversity, free speech, and a knack for bouncing back. Turning things around takes guts honest leaders, smart investments in things like education and healthcare, fairer economic rules, and a real push to come together instead of tearing each other apart. Most of all, it takes everyday people stepping up, listening, and holding those in power accountable.

The problems are real, but decline isn’t set in stone. With effort, empathy, and a little stubborn hope, Americans can change course and build a future that actually works for everyone not just the lucky few.