The liberal shift in the US has been blunted by ideological sorting

Plus: solar efficiency, buses that stop too often, and more

Welcome to The Update. In today’s issue:

The liberal shift in the US has been blunted by ideological sorting

Italian governments keep changing the voting system to benefit themselves

The liberal shift in the US has been blunted by ideological sorting

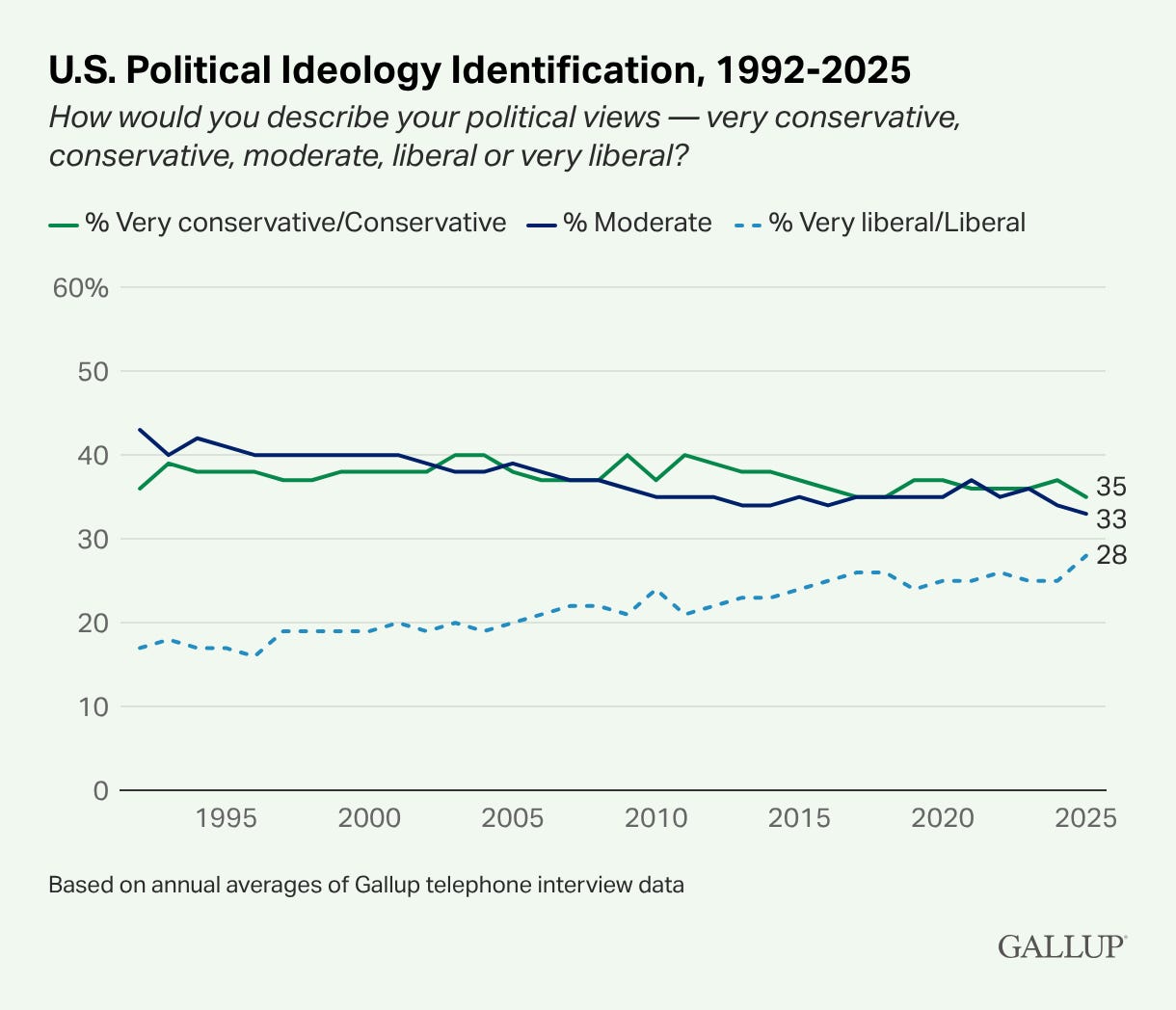

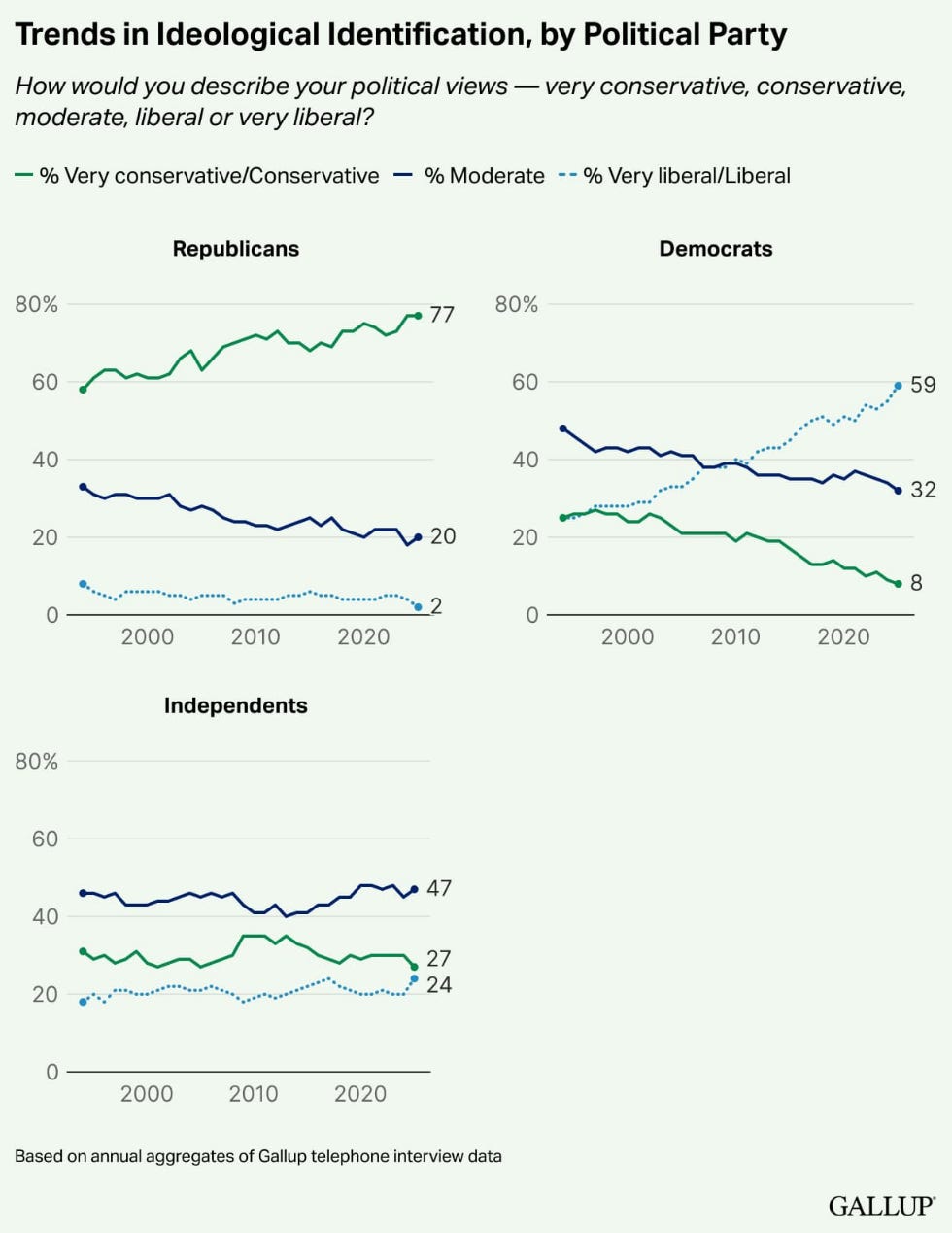

Americans are growing more liberal, according to Gallup. In the early 1990s, only 17–18 percent of Americans identified as liberals, and conservatives outnumbered them by more than 20 percentage points. Last year, that gap shrank to only 7 percentage points.

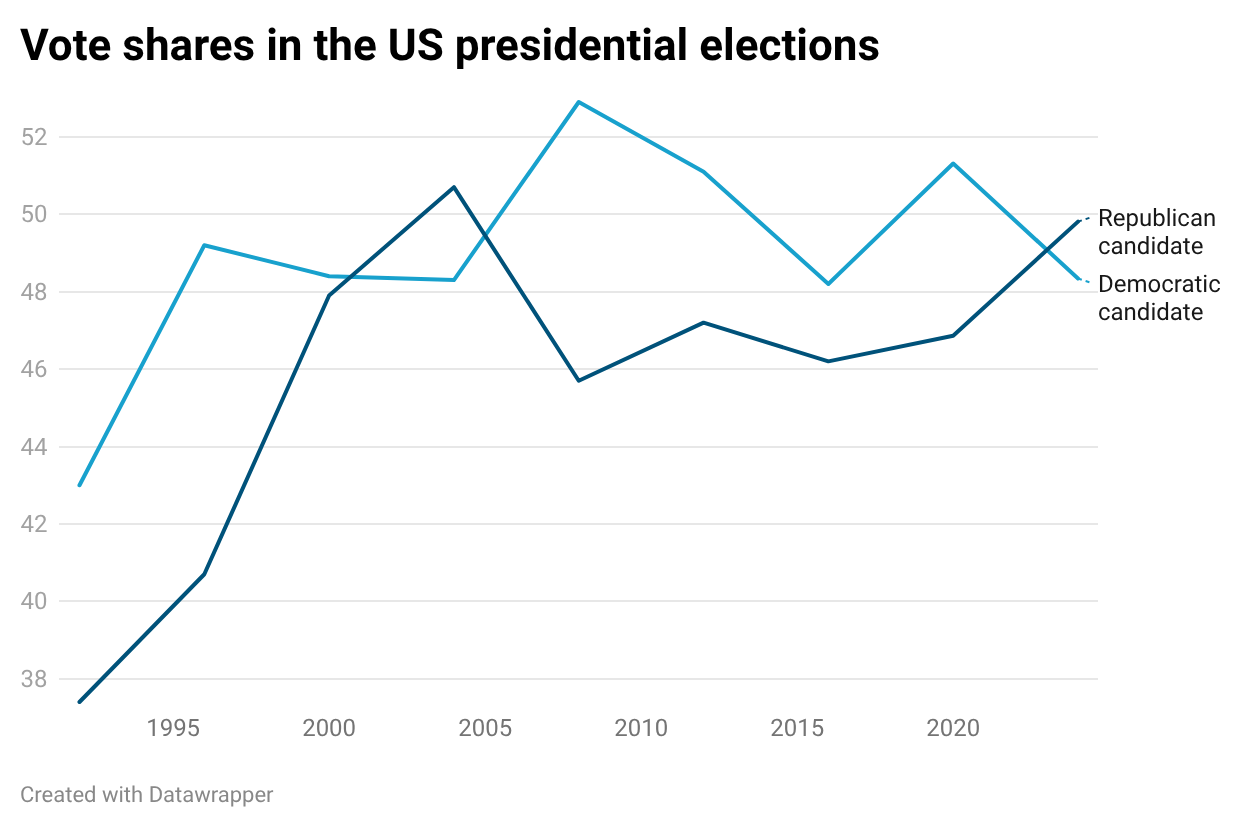

But this hasn’t translated into Democratic presidential victories the way Democrats might have hoped. During this time, Democratic and Republican vote shares in presidential elections have been relatively stable.

Electoral outcomes aren’t decided by the numbers of liberals and conservatives (and moderates) alone. They’re also affected by the fractions of each of these groups that vote for the Democrats and Republicans, respectively. And these fractions have changed, too. There’s been an ideological sorting among American voters: conservatives have become more likely to vote for the Republican candidate, and liberals have become more likely to vote for the Democratic candidate. But partly because there used to be many more conservatives than liberals, this ideological sorting has favored the Republicans. The number of liberal votes they’ve lost is much smaller than the number of conservative votes the Democrats have lost. In this way, the swing toward liberalism has largely been offset.

What solar panels can teach us about effectiveness gaps

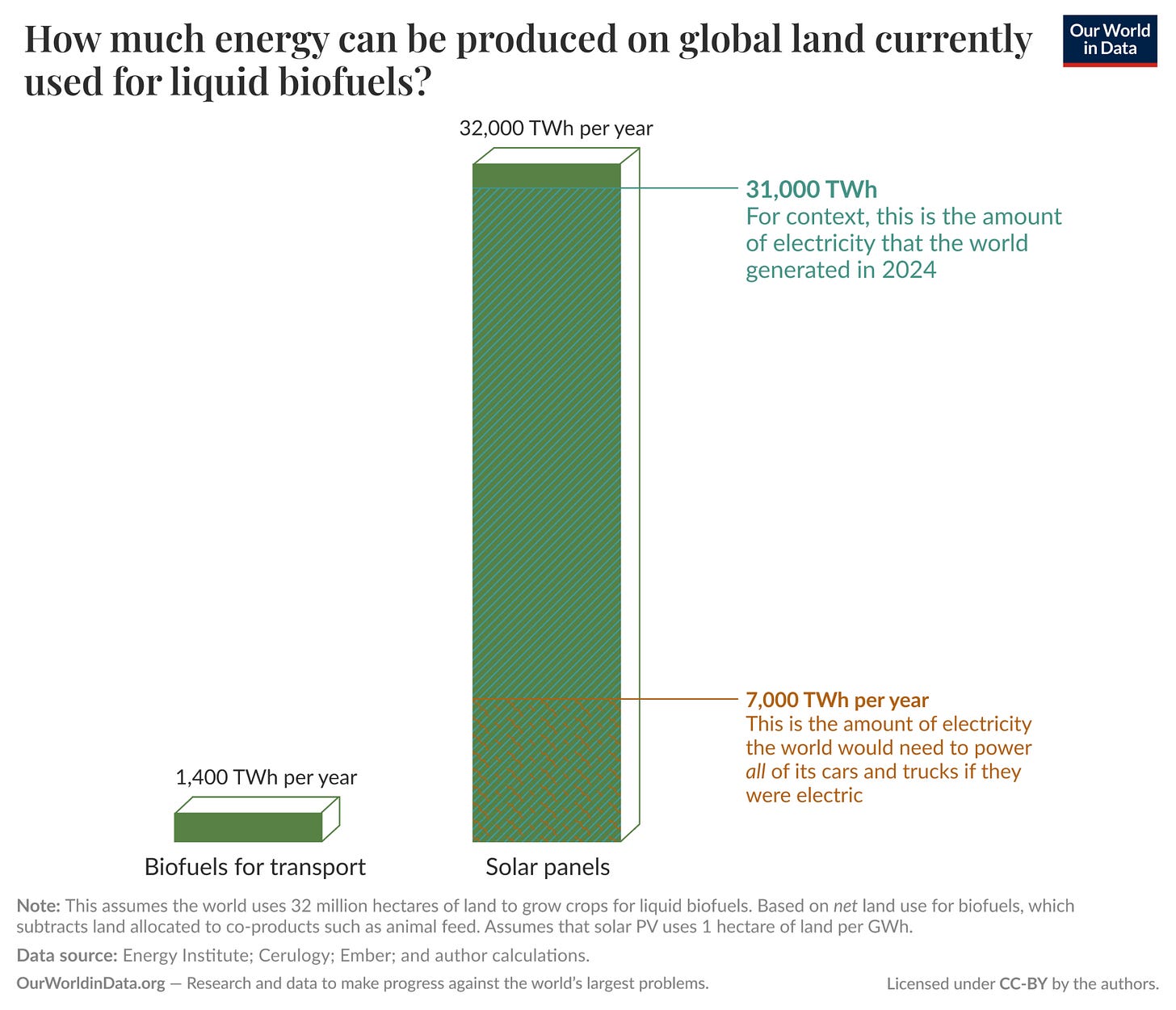

Hannah Ritchie and Pablo Rosado have published a great chart on Our World in Data about how much energy solar panels produce relative to liquid biofuels. Currently, at least 320,000 square kilometers of land – roughly the size of Germany or Poland – are used for the production of liquid biofuels for road transport. This yields 1,400 terawatt hours per year, but if we instead used this land for solar panels, it would yield 32,000 terawatt hours per year: 23 times as much.

But it gets even more extreme. Biofuels are used to power combustion engines, which waste most of the energy, primarily as heat. Consequently, only four percent of the world’s energy demand for transport is covered by biofuels. Electric cars are much more energy efficient, to the point that less than a quarter of the land that’s currently used to produce biofuels would suffice to power all cars and trucks if they were electric.

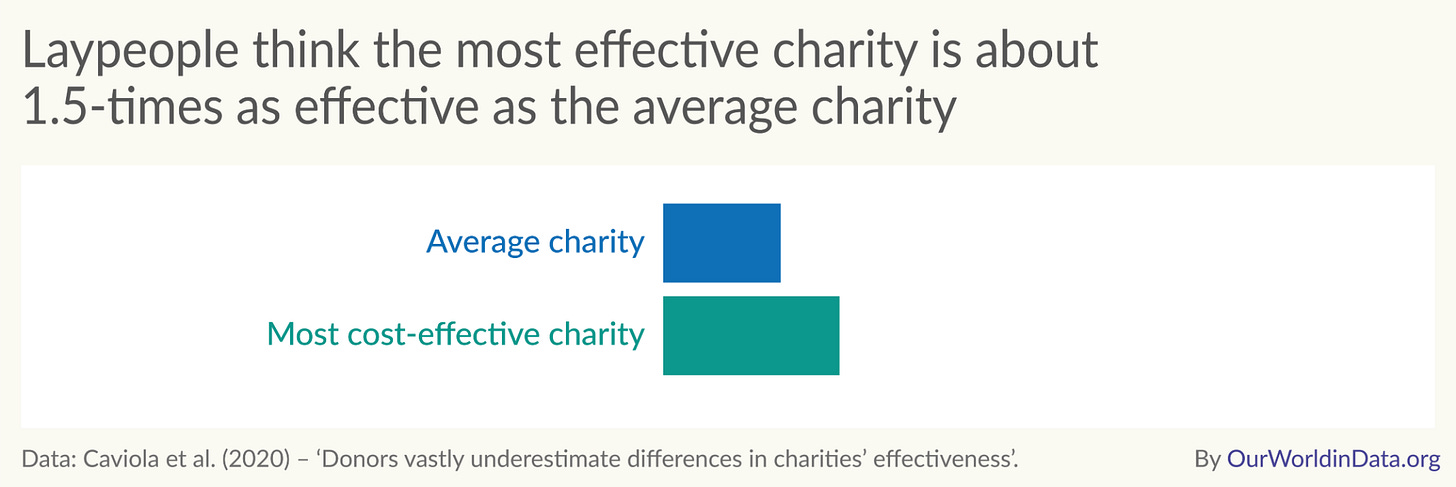

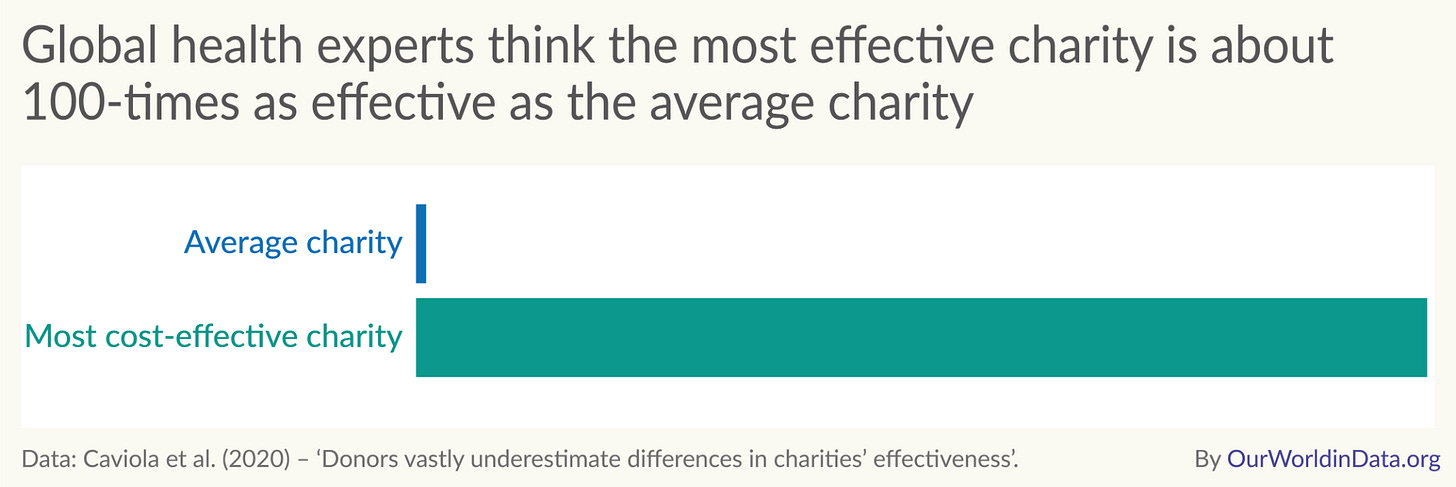

I think people often underestimate how much the effectiveness of different solutions can vary. We see it in other domains, such as healthcare and charity. Research shows that the average person thinks the most effective charities helping the global poor are about 1.5–2 times as effective as the average such charity. But charity experts estimate that the difference is in fact a factor of 100.

Why are the differences so large? It’s not because of fraud or wasteful spending on administration costs, as many people think. Instead, the main reason is that some charities employ much more effective interventions than others. If you’re seeking to save lives with a given amount of money, it’s much more effective to distribute bednets against malaria than to perform complex surgery. And if you’re seeking to produce energy with a given amount of land, it’s much more effective to set up solar panels than to produce biofuels. There’s no natural tendency for different solutions to be similarly effective – they can differ enormously. We should pay far more attention to these effectiveness gaps.

American buses have too many stops

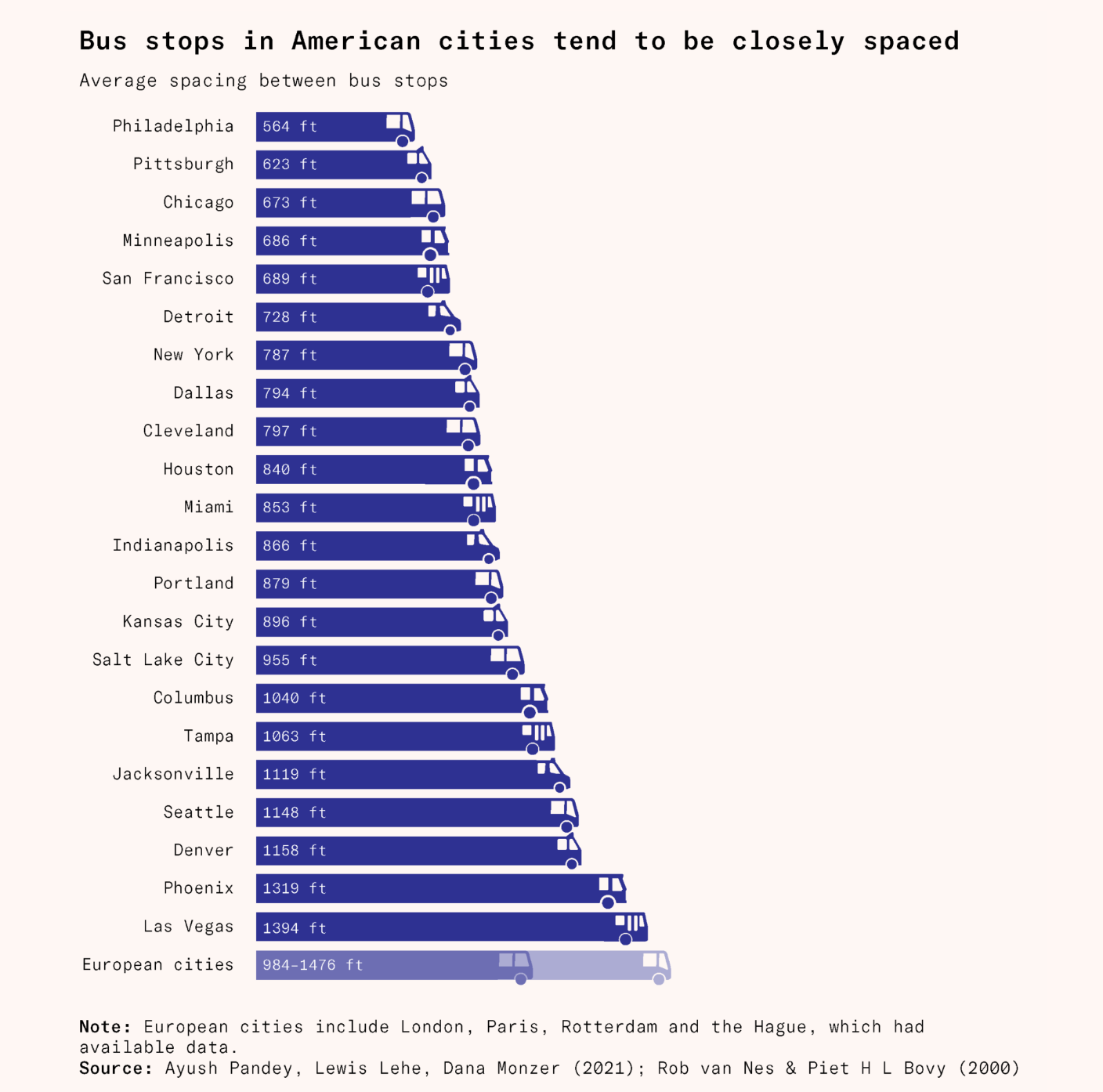

How often should the bus stop? Frequent stops can reduce walking distance for riders, but at the same time, it slows the bus down. In an article for Works in Progress, Nithin Vejendla argues that American cities haven’t gotten this tradeoff right. Whereas bus stops in European cities tend to be at least 300 meters apart, that distance is 205 meters in Chicago, 190 meters in Pittsburgh, and as little as 172 meters in Philadelphia. This reduces speed at relatively small gain. Many riders have multiple stops nearby, which means that closing one of them only has a marginal effect on walking distance. Consequently, Nithin argues that American cities should let their buses run with fewer interruptions.

What does ‘AI bubble’ even mean?

The debate on whether we’re in an AI bubble continues with undiminished strength, but it’s plagued by confusions. The economist Alex Imas makes an important distinction that’s often missed, especially by AI skeptics. It’s one thing to say that valuations of AI companies are currently too high – a financial bubble – and it’s quite another to say that AI will never live up to the hype about real-world impact – a hype bubble. As Alex notes, the chances that AI is a hype bubble seem much lower than the chances that it’s currently a financial bubble.

Another confusion stems from the connotations of irrationality that the word bubble often carries. Many people seem to believe that a tech stock crash reveals that investors must have been irrational. But that need not be the case. It’s incredibly hard to predict the future of technology, and even rational investors will sometimes overshoot. If you never overshoot, it’s evidence that you’re too cautious.

Rob Wiblin adds a further reason to expect rational investors to cause an AI bubble: the outsized returns if superhuman AI arrives soon. He estimates that if investors believe there’s a 10 percent chance the economy will soon grow tenfold, stock prices should roughly double now – even though there’s a 90 percent chance they will crash. High AI valuations don’t necessarily reflect a high probability of transformative near-term impact.

Italian governments keep changing the voting system to benefit themselves

Italian prime minister Giorgia Meloni is planning to revise the country’s voting system ahead of the next elections, scheduled to be held in 2027. While some countries require a supermajority, a referendum, or two votes with an election in between to change the voting system, a simple majority in parliament is enough in Italy. This has led to multiple revisions aimed at favoring the sitting government in recent decades. The current proposal is to offer bonus seats to the largest coalition if it clears a threshold. If elections were held today, the government coalition would get those bonus seats.

In brief

Caleb Watney writes in The Wall Street Journal about the National Science Foundation’s new Tech Labs initiative, which will provide large and long-term funding to research teams. Today, most grants support small projects, and there’s a need for funding that’s dedicated to the most ambitious scientific missions. Plans are underway to extend this model to the funding of medical research.

Hannah Ritchie has published an in-depth article showing that people are optimistic about their own lives but pessimistic about society. Why might that be? Hannah discusses two theories. First, while we have direct knowledge of ourselves, information about society is filtered through the media, which has a well-known negativity bias. Second, we exercise less agency over society than over our own lives, and this can drive feelings of helplessness and pessimism.

That’s all for today. If you like The Update, please subscribe and share with your friends.

Israel too, allows changing voting laws with a simple majority.

It has been used multiple times, but usually without odious abuse.

The current government is talking about reducing the voting age from 18 to 17, wick will definitely help the current coalition.

Last election wouldn't have given a clear win to Netanyahu had the former coalition gone through with it's plan to reduce the threshold to enter parliament from 3.25% to 1.5% as they almost did.