Why all the college catastrophizing?

Costs are falling, returns are holding up, and graduates aren’t being displaced by AI

Welcome to The Update. In today’s issue:

The falling cost of college in the US

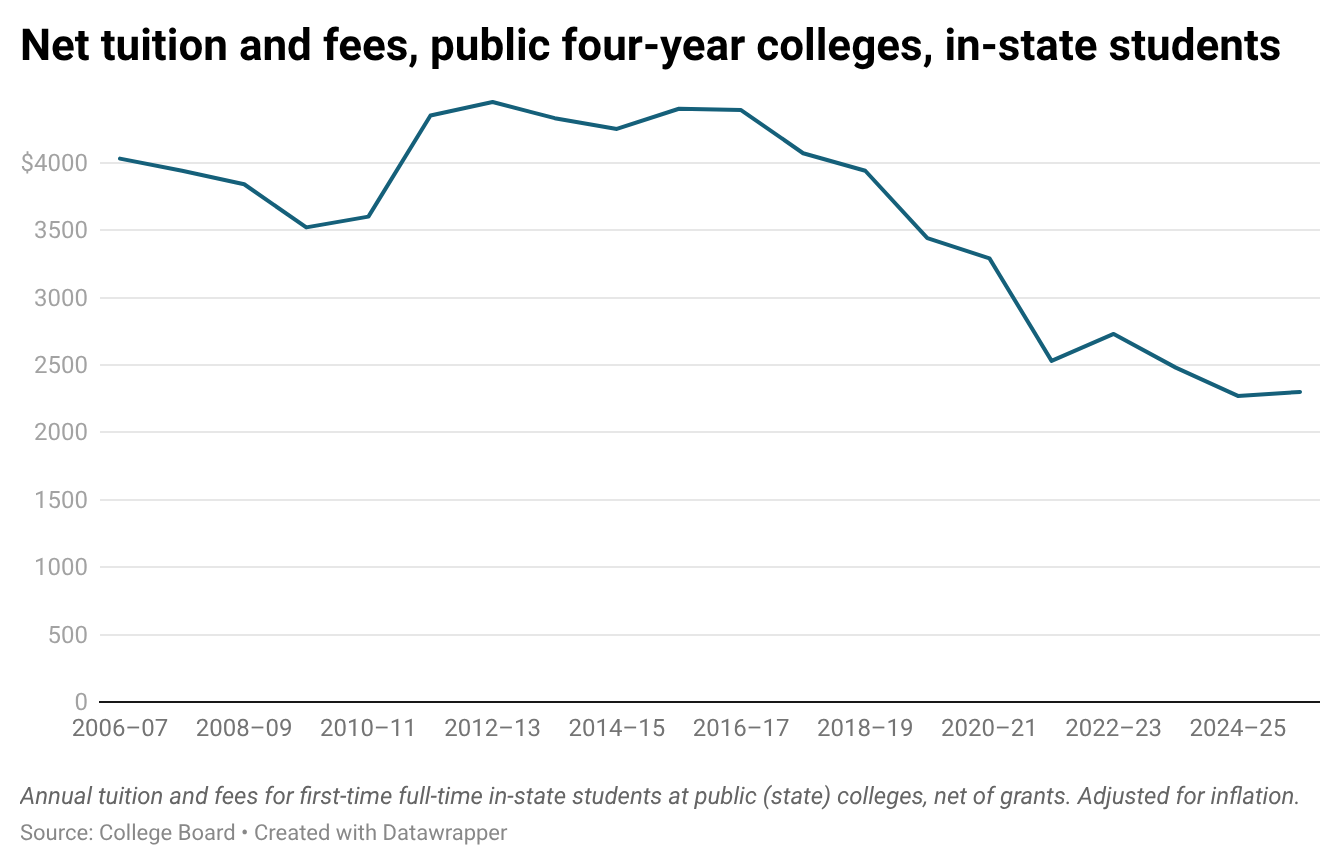

Is college really worth it these days? The American discourse about the value of going to university has a negative slant, focusing on costs, student debt, and the idea that college graduates will be especially vulnerable to automation. But many of these claims are exaggerated. In fact, the net cost of US undergraduate education has fallen in recent years, especially at public (state) colleges.

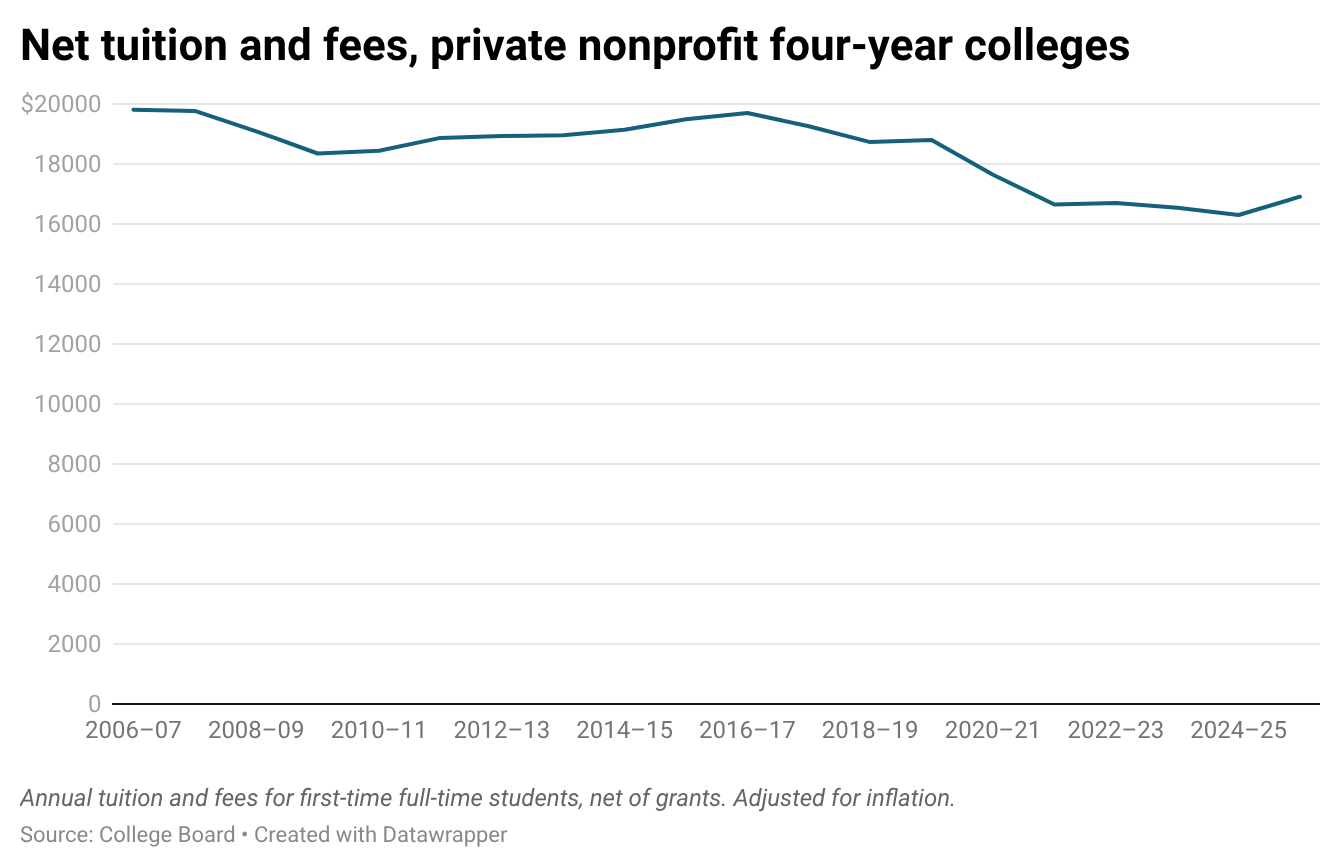

Private nonprofit colleges are more expensive, but the average net cost has fallen there, too:

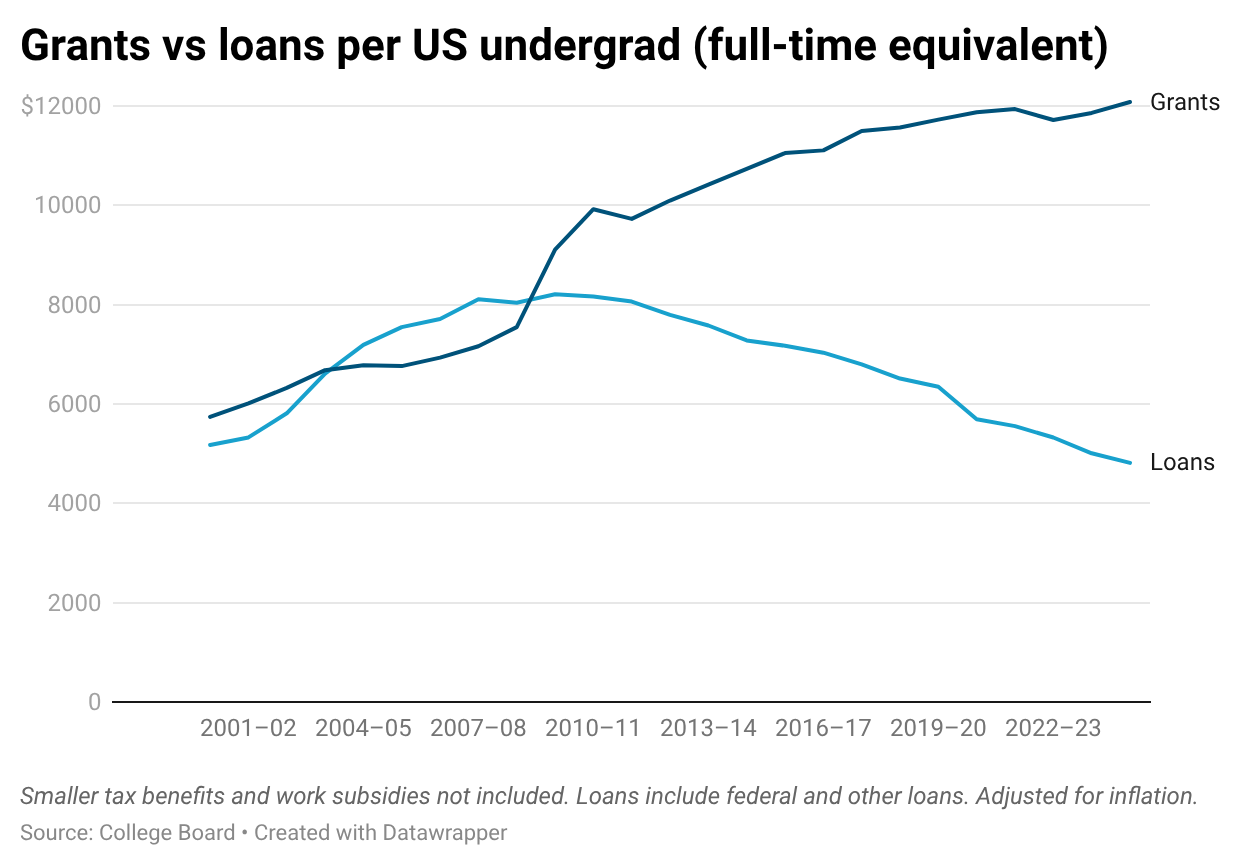

The debate over the cost of college often focuses on the much higher sticker price, which few students actually pay. It’s more relevant to look at the average net cost. A major reason this has declined is the increasing value of grants.

This expansion of grants has also contributed to a 40 percent fall in new undergraduate student loans since 2010. Non-repayable support – including grants as well as tax benefits and work subsidies – is now almost three times larger than repayable support (loans).

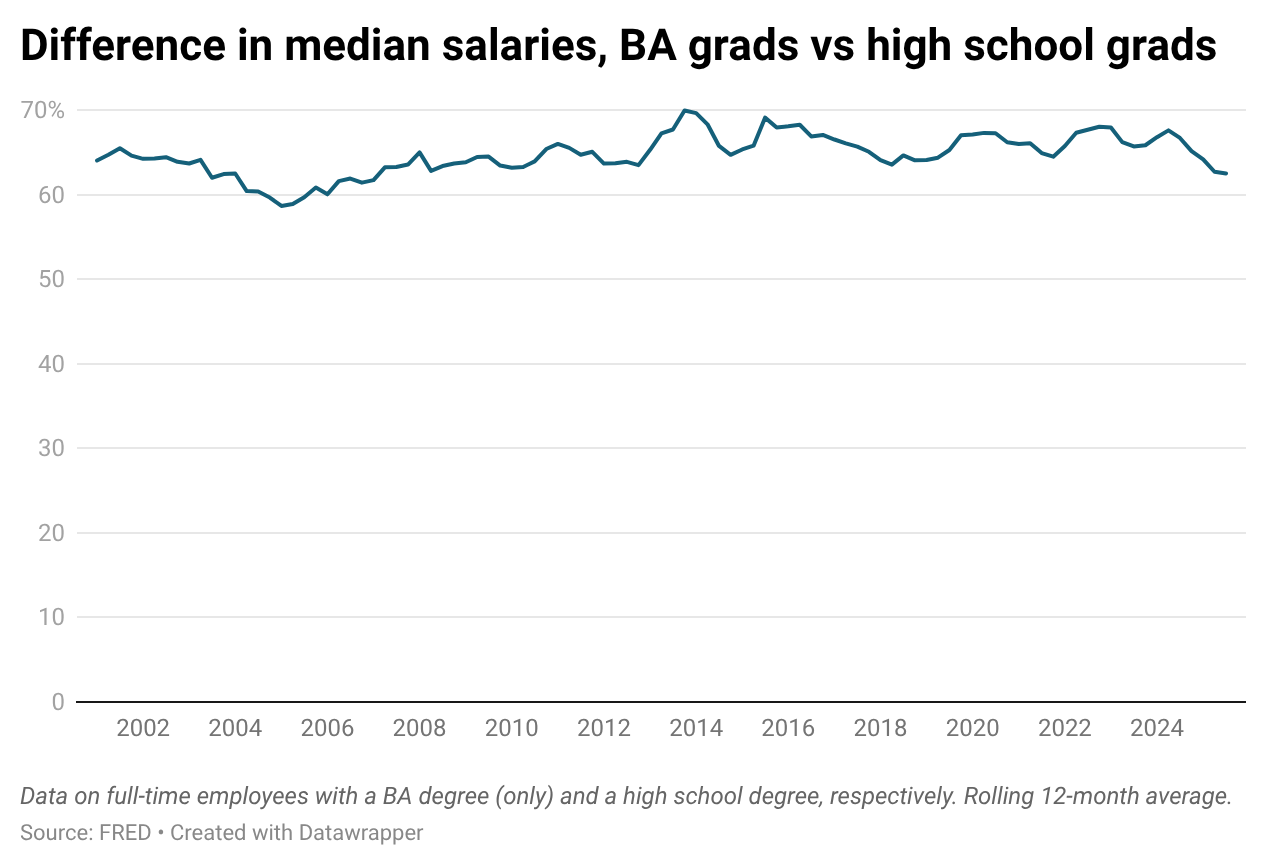

At the same time, the college wage premium has remained fairly constant:

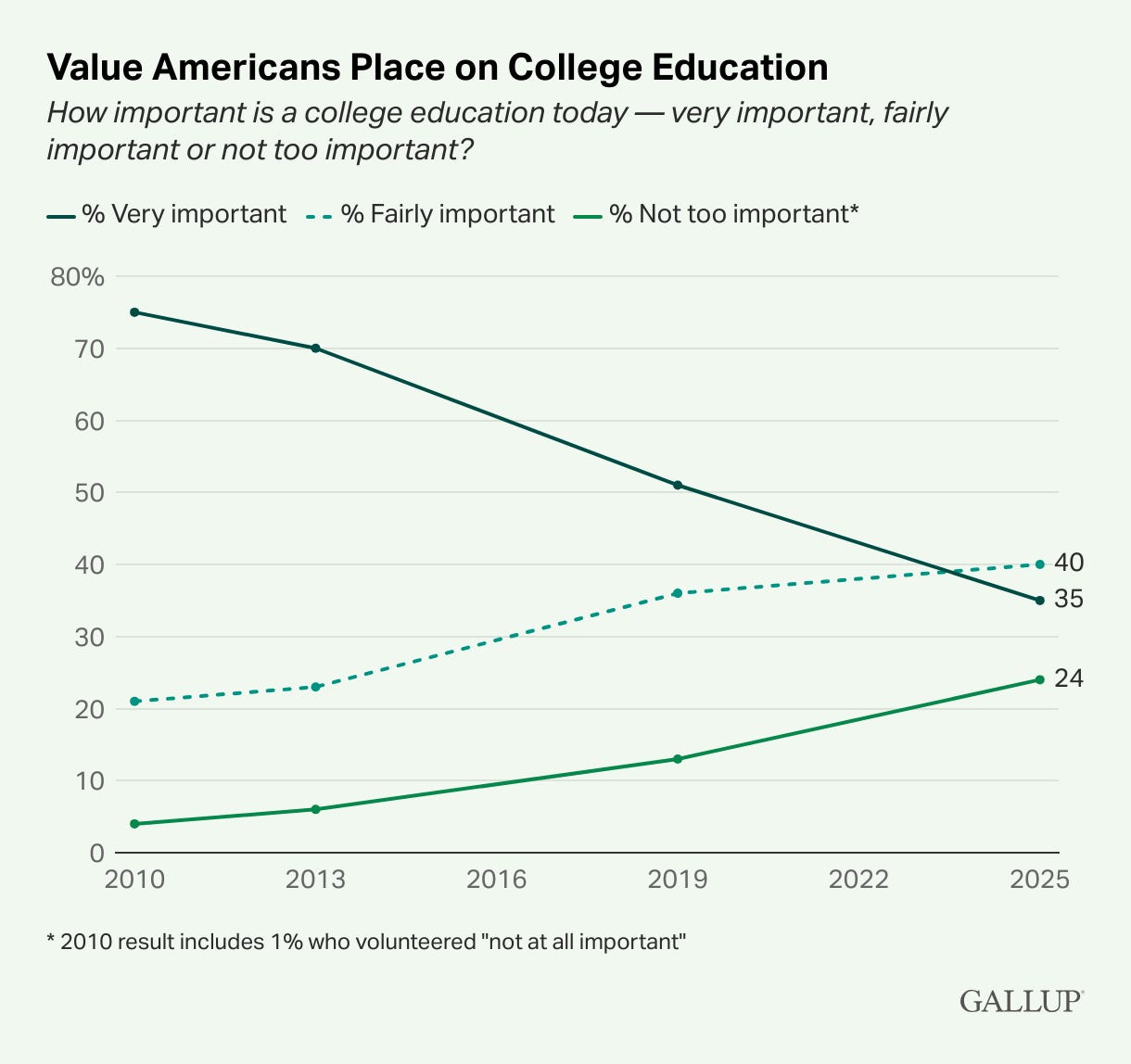

But though the returns from college have held up – and it’s cheaper to attend – Americans’ perceptions of the value of college have dropped quickly.

Some might think this pessimism is justified in light of the rise of LLMs, but given how far back it stretches, it can hardly be rooted in that. It doesn’t reflect changes in the objective value of college and is better seen as a broad expression of disapproval. Americans have grown to distrust many of the country’s institutions, and college is among them.

College grad unemployment isn’t about AI

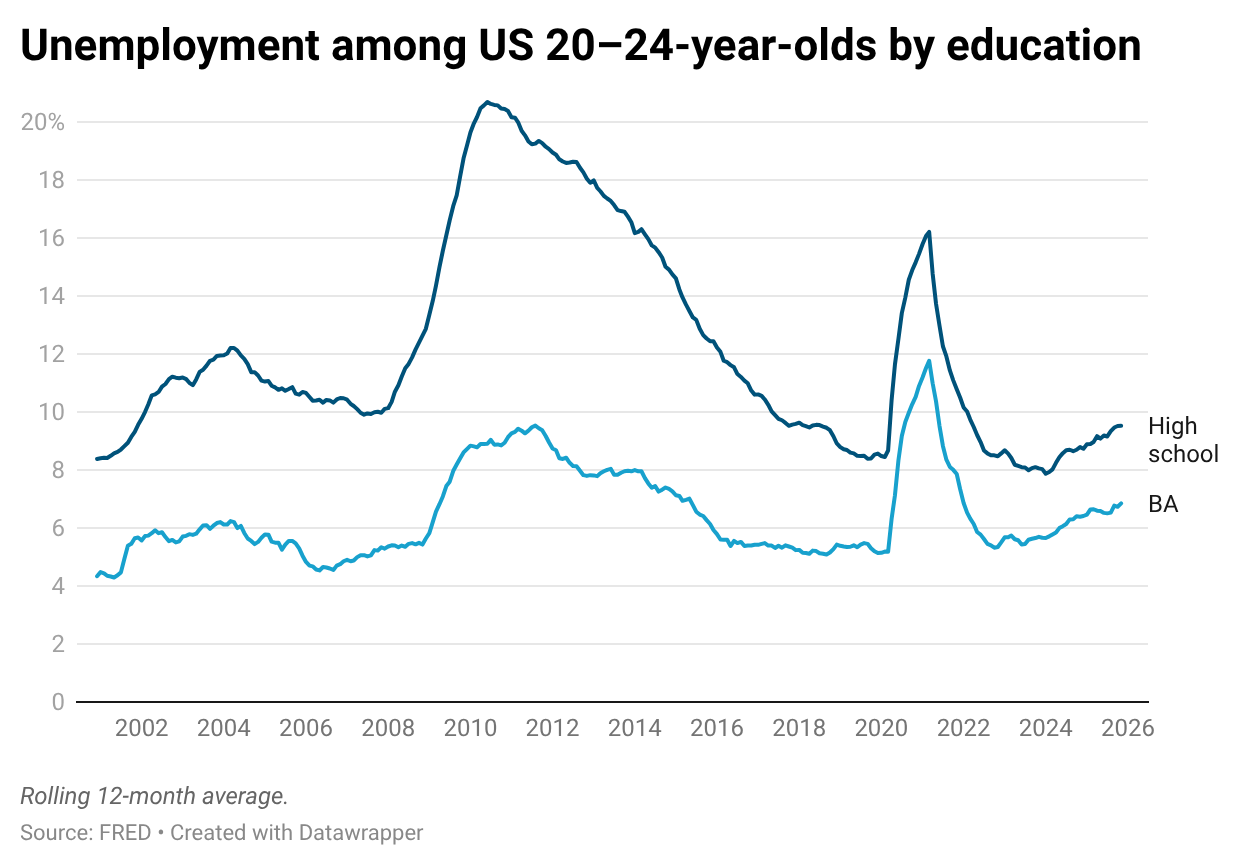

In any case, the suggestion that AI is already having a disproportionate impact on college graduates is overblown. While a rising share of young college graduates is indeed unemployed, that’s true of young high school graduates, too. There’s a simple and well-known explanation for this pattern: in an economic downturn, unemployment rises fastest among those with a weaker position in the labor market.

As Guy Berger points out, this type of chart actually understates the difference between high school graduates and college graduates. Among 20–24-year-olds, high school graduates tend to have more work experience than college graduates, meaning the comparison isn’t like-for-like. Unemployment among the most inexperienced high school graduates – 18–19-year-olds – is 15 percent, underscoring that a college degree still matters in the American labor market.

Forecasters uncertain after the Maduro raid

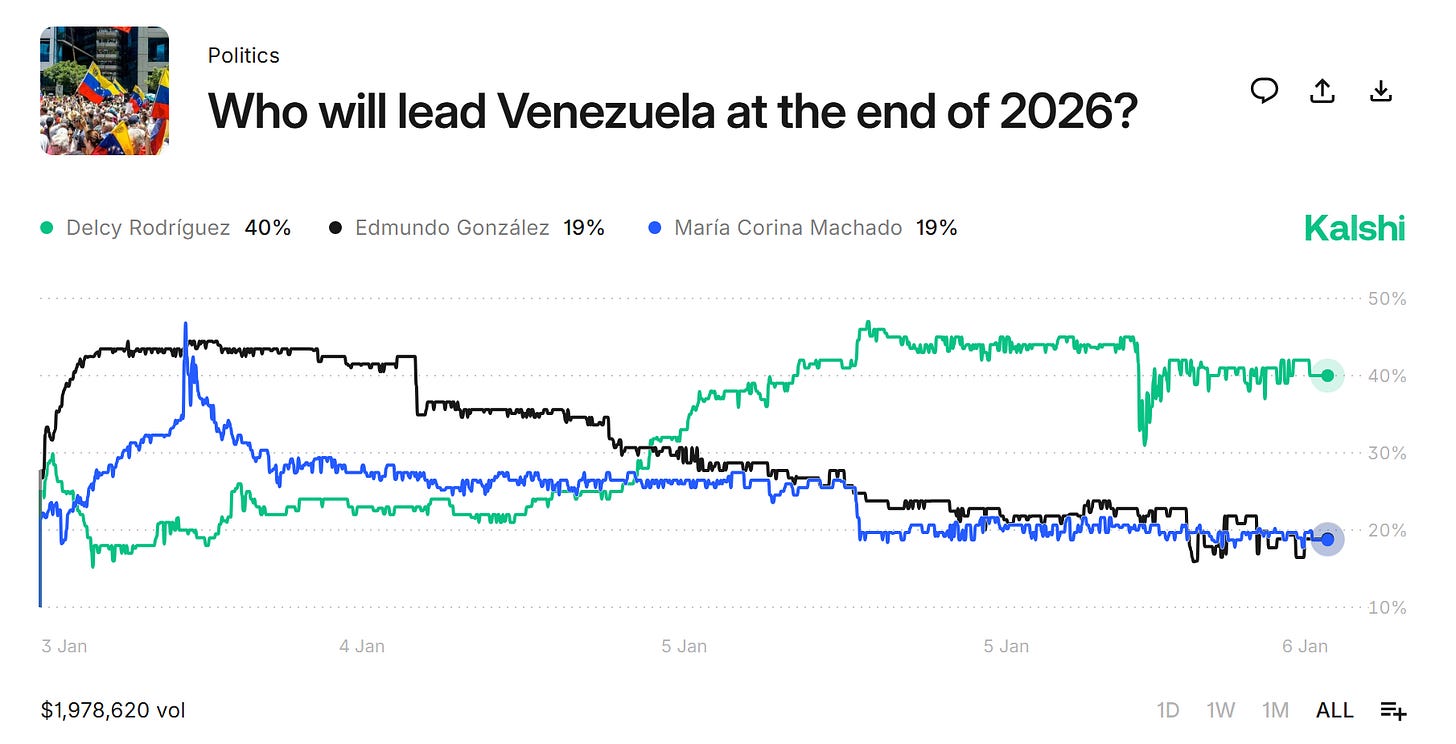

The US raid on Caracas that brought Venezuelan leader Nicolás Maduro to New York has led to intense speculation about what’s going to happen next. As always, it’s useful to study prediction markets and professional forecasters. Immediately after the raid, Kalshi traders expected an opposition politician – Edmundo González or María Corina Machado – to be in power by the end of the year, but they currently consider it equally likely that Maduro loyalist Delcy Rodríguez will remain interim president. The predictions are changing fast, reflecting the uncertainty of the situation.

In reaction to the raid, many have also raised their estimates of US interventions elsewhere. Expert forecasters at Sentinel Global Risks Watch believe there’s a 67 percent chance that the US will strike another Latin American country this year. They also estimate a 36.5 percent chance that by the end of this presidency, the US will either have full control of Greenland or control its defense via a compact of free association.

New York’s congestion pricing is working

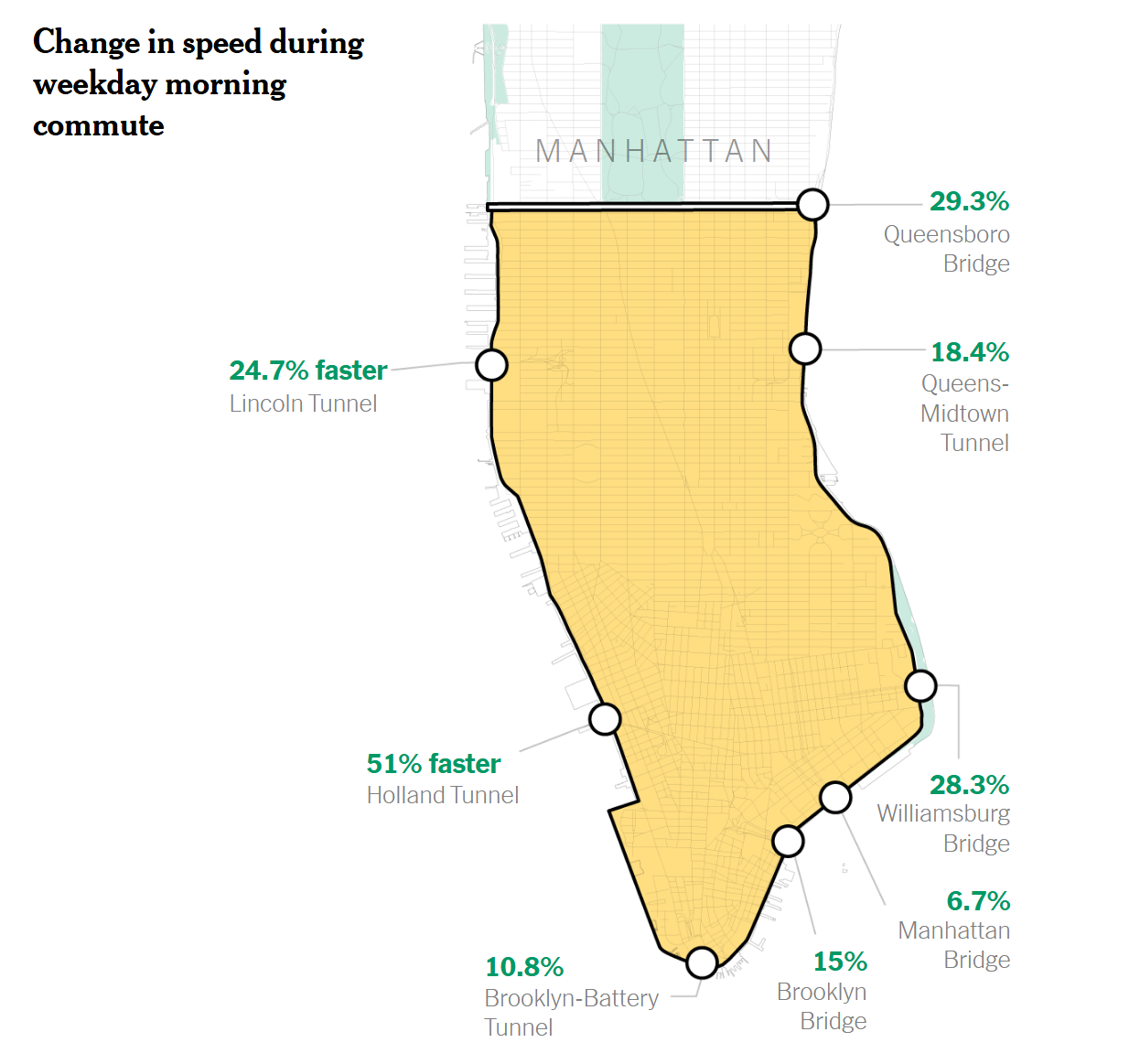

A year after the introduction of congestion pricing in New York, the number of cars entering the congestion zone has declined, and driving speeds on many of the tunnels and bridges to Manhattan have risen. There has also been a reduction in the number of car accidents and noise complaints. New Yorkers were opposed to the plan before it was introduced, but have since become much more positive about it.

American productivity expected to sail ahead

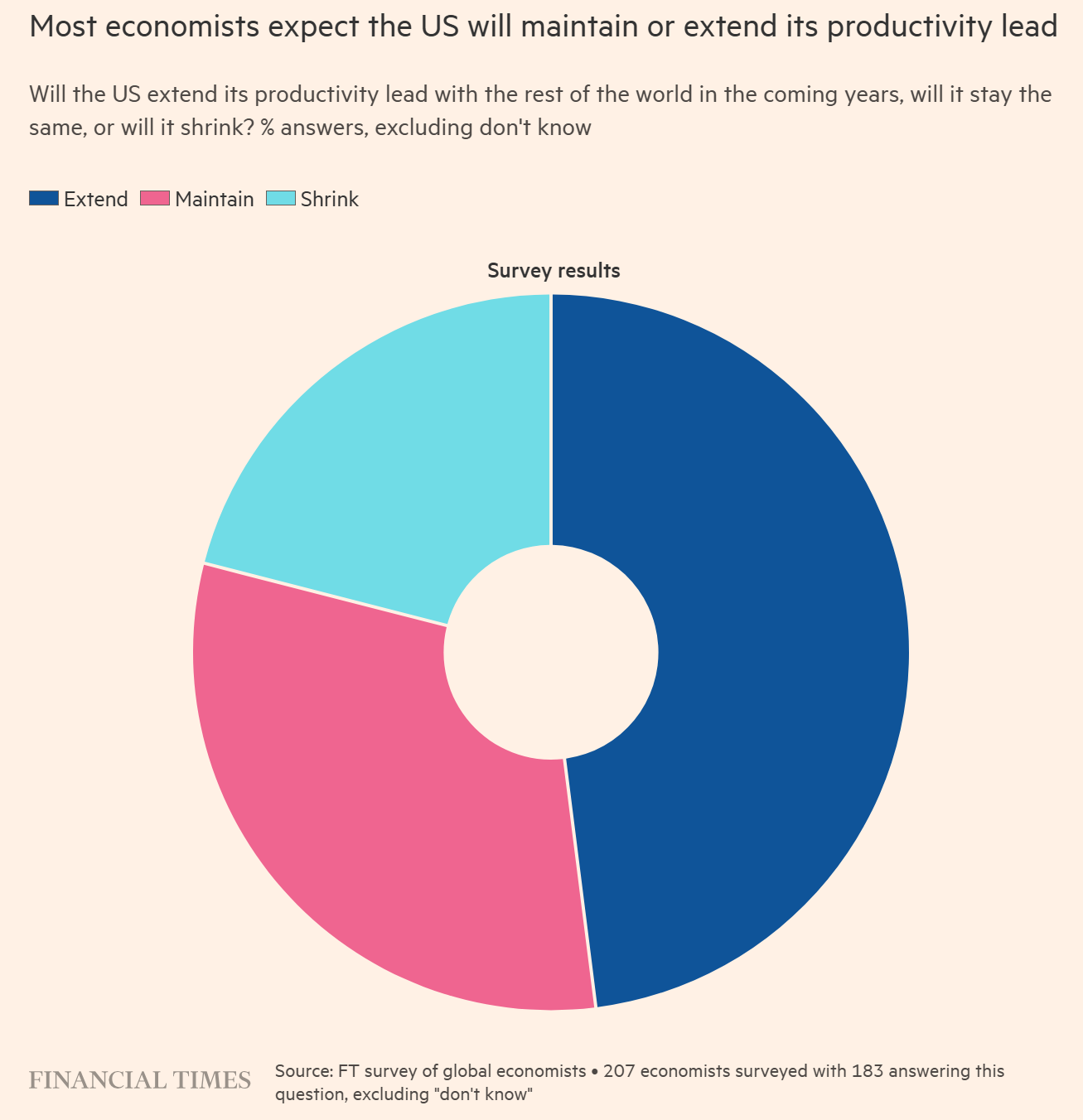

In a Financial Times survey of 183 economists, almost half expected the US to increase its productivity lead over other countries in the years to come, while less than a quarter expected it to shrink.

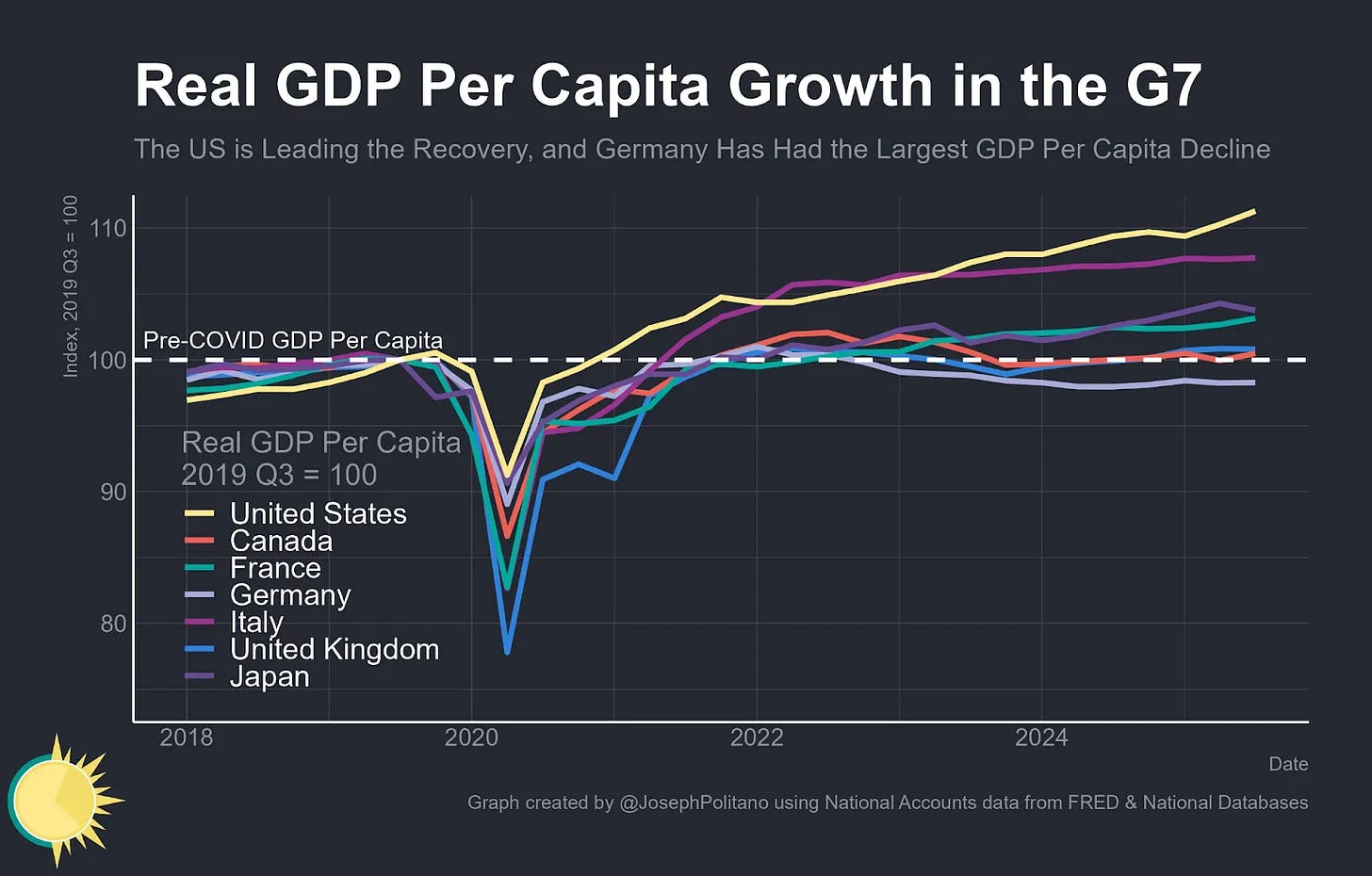

As I reported in my last newsletter, the US has recently outgrown the rest of the G7.

You’d expect emerging markets to do better, since it’s easier to grow from a lower level. At the start of the century, they did indeed outgrow the US – but as Robin J Brooks reports, that has changed in the last decade. From Latin America to much of Asia, emerging markets have not grown faster than the US (though China and India are two important exceptions). We’re not seeing as much convergence as people once expected.

BYD overtakes Tesla

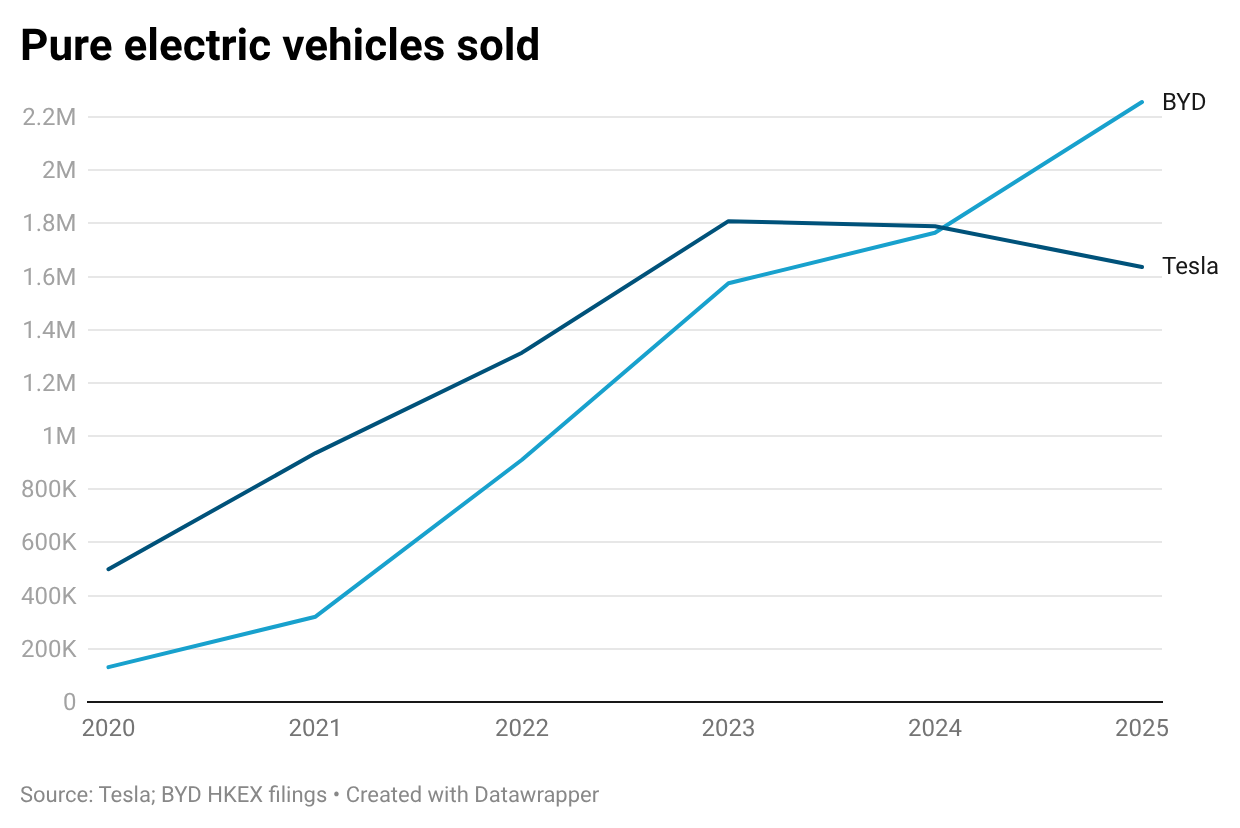

Chinese carmakers have quickly increased their sales of electric vehicles and now have eight of the ten best-selling models. BYD’s sales of pure EVs have grown almost twentyfold since 2020, and the company recently overtook Tesla to become the largest seller by number of vehicles (though Tesla likely remains the largest by dollar value, its cars being more expensive).

The messiness heuristic for keeping your job

How can you reduce the risk that your job will be among the first to be automated by AI? The economist Luis Garicano suggests a useful heuristic: choose a messy job. Today’s AI systems shine when they’re given well-defined and separable tasks – like routine contract writing or basic customer support – meaning that jobs that mostly consist of such tasks are more susceptible to automation. By contrast, they struggle with jobs like people management and courtroom litigation, which involve multiple tasks that are bundled together in ways that are hard to specify in advance.

Of course, this is only a heuristic, and as such it needs to be applied with caution. As David Rein pointed out in a recent podcast on METR’s metrics of AI capabilities, opinions diverge on what counts as messy. That said, I think it’s a useful first pass. It fits the notion that AI capabilities are jagged, which I covered on 23rd December. Today’s systems are much stronger on some tasks than others, making it hard to automate jobs that involve many tightly integrated tasks.

Immigration is sharply down in Western countries

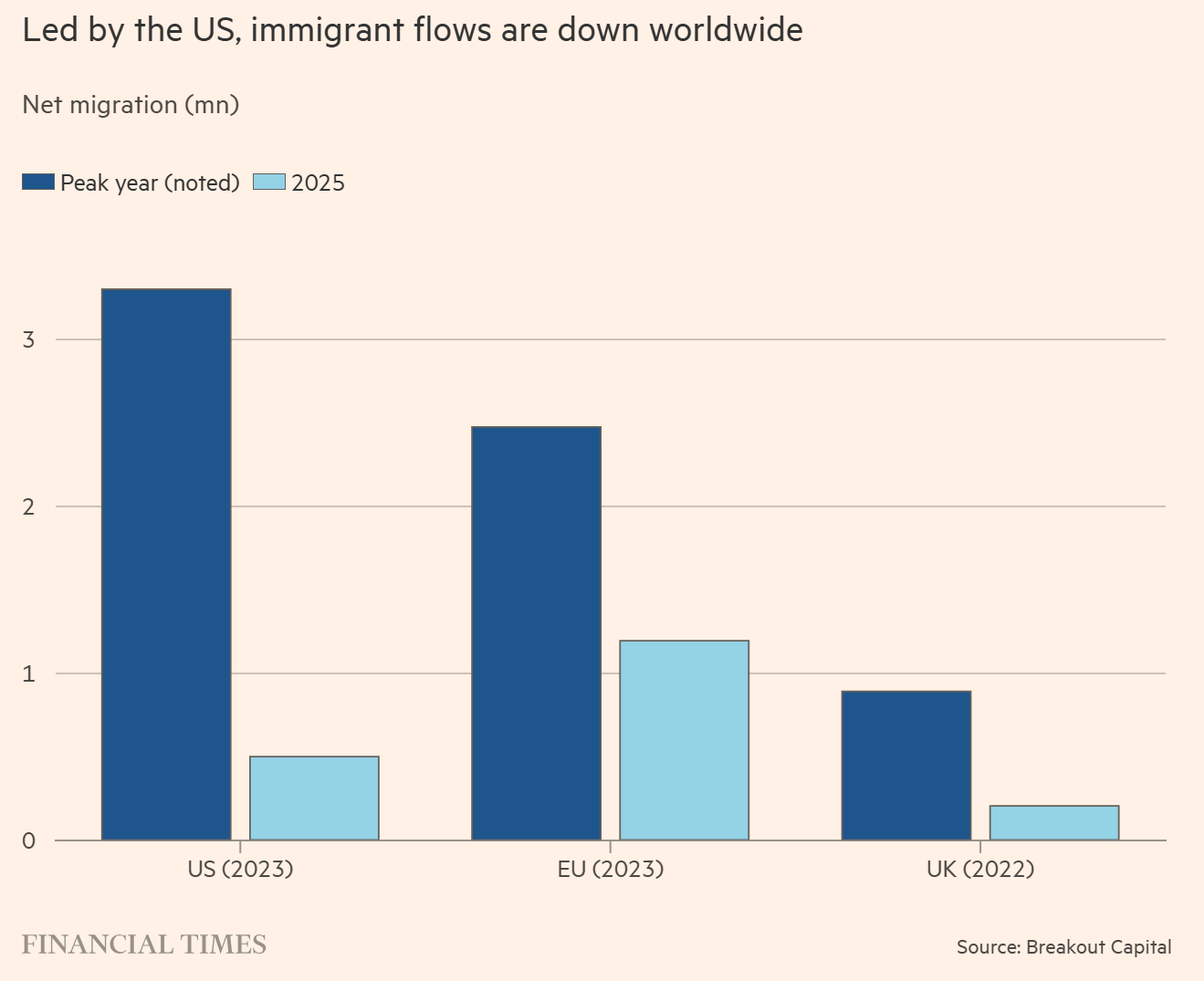

In a Financial Times article on the year to come, Ruchir Sharma identifies an underreported trend from the past year: falling immigration to Western countries. It’s not just about the US, even though the decline has been steepest there. From recent peaks, EU immigration has halved, and UK immigration has fallen by three quarters.

One does not simply create a European nationalism

The recent US National Security Strategy used pointed language against the EU, claiming it undermines ‘political liberty and sovereignty’ in Europe. But in a Project Syndicate article, the economist Ricardo Hausmann argues that Europe’s problem isn’t that the EU is too strong, but that it’s too weak. To compete with the US, China, and Russia, the EU must become more like a nation. And that, in turn, requires a European nationalism.

Hausmann quotes the Italian statesman Massimo d’Azeglio, who said after the unification of Italy: ‘We have made Italy; now we must make Italians.’ This way of thinking is common among EU federalists, but in my view, it’s naive. The different parts of Italy had much more in common than places like Bulgaria and Denmark have today. Moreover, it was a much less democratic era, where elites had more room to impose a national identity from above. In the last few decades, voters have repeatedly rejected deeper EU integration. Today, there’s much less leeway to reshape national identities from the top down than the likes of Hausmann seem to imagine.

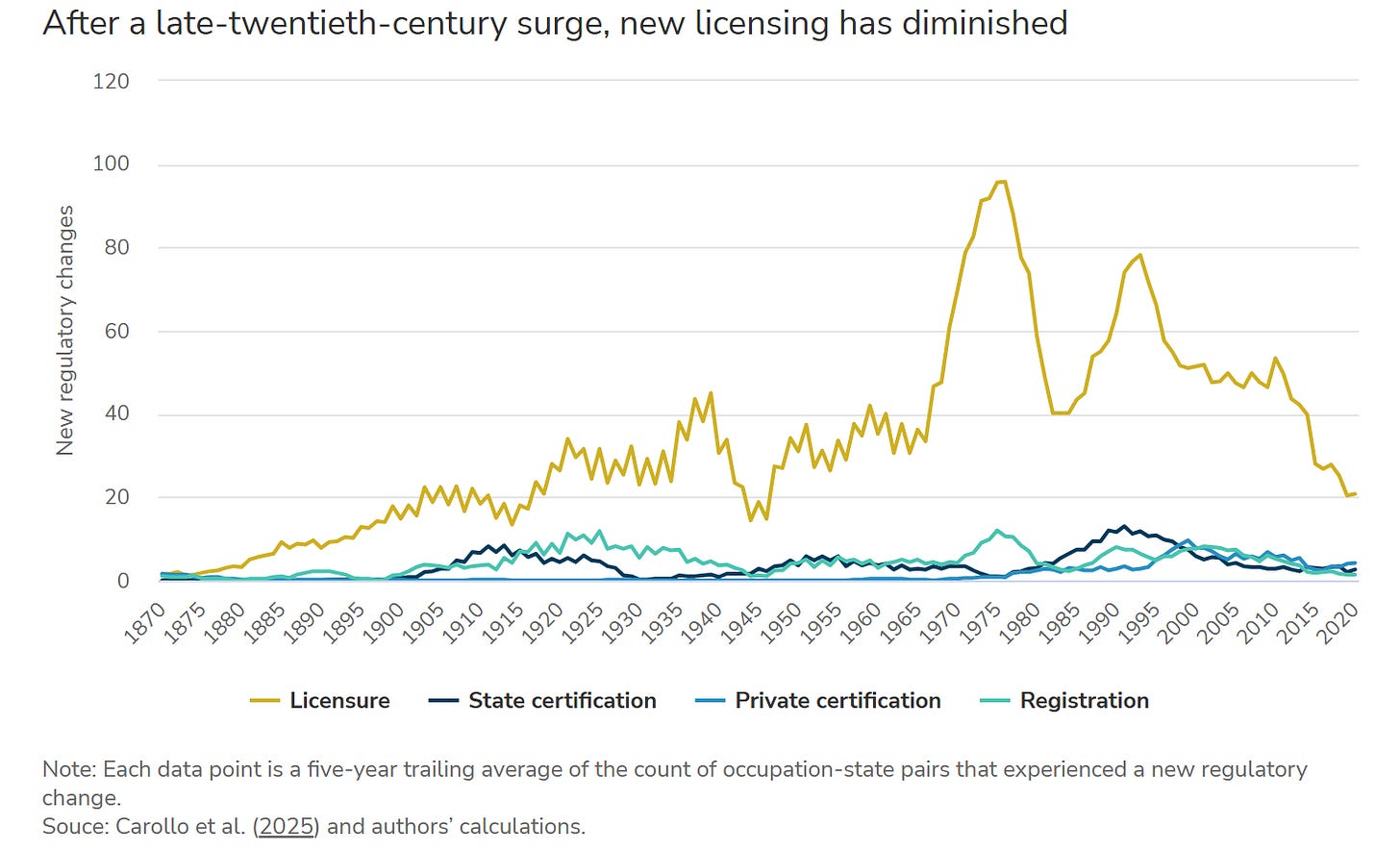

American occupational licensing has stabilized

Free-market economists have long criticized how widespread occupational licensing is in the US. Alex Tabarrok writes that while doctors and nurses do need licenses, it’s counterproductive to require them of hair braiders and interior designers. But how has occupational licensing changed over time? The Federal Reserve Bank of Minneapolis has published a useful dashboard that helps us answer that question. Licensing requirements surged in the 1970s and then again in the 1990s, but in recent years, growth has tapered off.

The dashboard also has data on the share of workers with an occupational license. Among all workers, this number has essentially been flat over the last five years, at roughly 21.5 percent. I didn’t find data for hair braiders specifically, but the number for hairdressers, hairstylists, and cosmetologists is 68 percent.

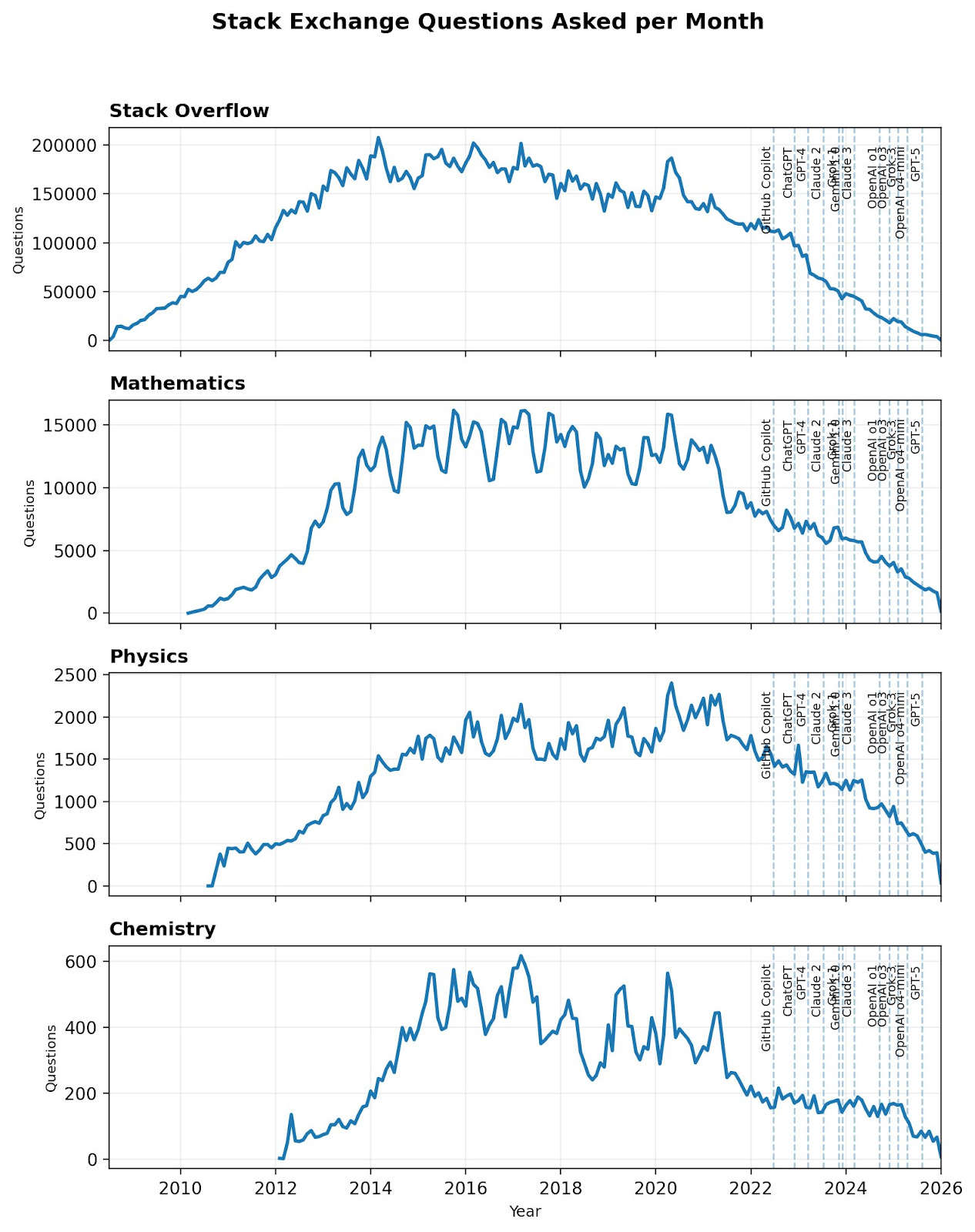

The end of Stack Exchange

Since 2008, people have used Stack Overflow to ask programming questions for other users to answer. Over time, sites on other topics were added to what became the Stack Exchange network. For a while, it flourished, with hundreds of thousands of questions asked each month. But now activity has all but ceased, as people increasingly rely on LLMs instead.

Activity at the more advanced MathOverflow remained stable for longer, but as the mathematician Daniel Litt reports, it has also seen a sharp decline after the advent of reasoning models in 2025.

That’s all for today. If you like The Update, please subscribe and share with your friends.

It’s actually an excellent time to be a prospective college student in the US. As a result of the abrupt contraction in the birth rate after the 08 financial meltdown, incoming cohorts are considerably smaller than their predecessors.

"It doesn’t reflect changes in the objective value of college and is better seen as a broad expression of disapproval"

Would you be open to the idea that college still selects for people aiming at better career outcomes but that it is not providing the services they need for that?

My anecdotal gloss from going to university in the US in the 2010s was that I was surrounded by people aiming to have great careers but even the business school undergrads found the classes less than ideal for giving them the skills they actually needed.

In other words it could be people are dissatisfied because college feels more like a tax to achieve a certain level of employability (due to prestige). Rather than something providing them useful knowledge or skills.