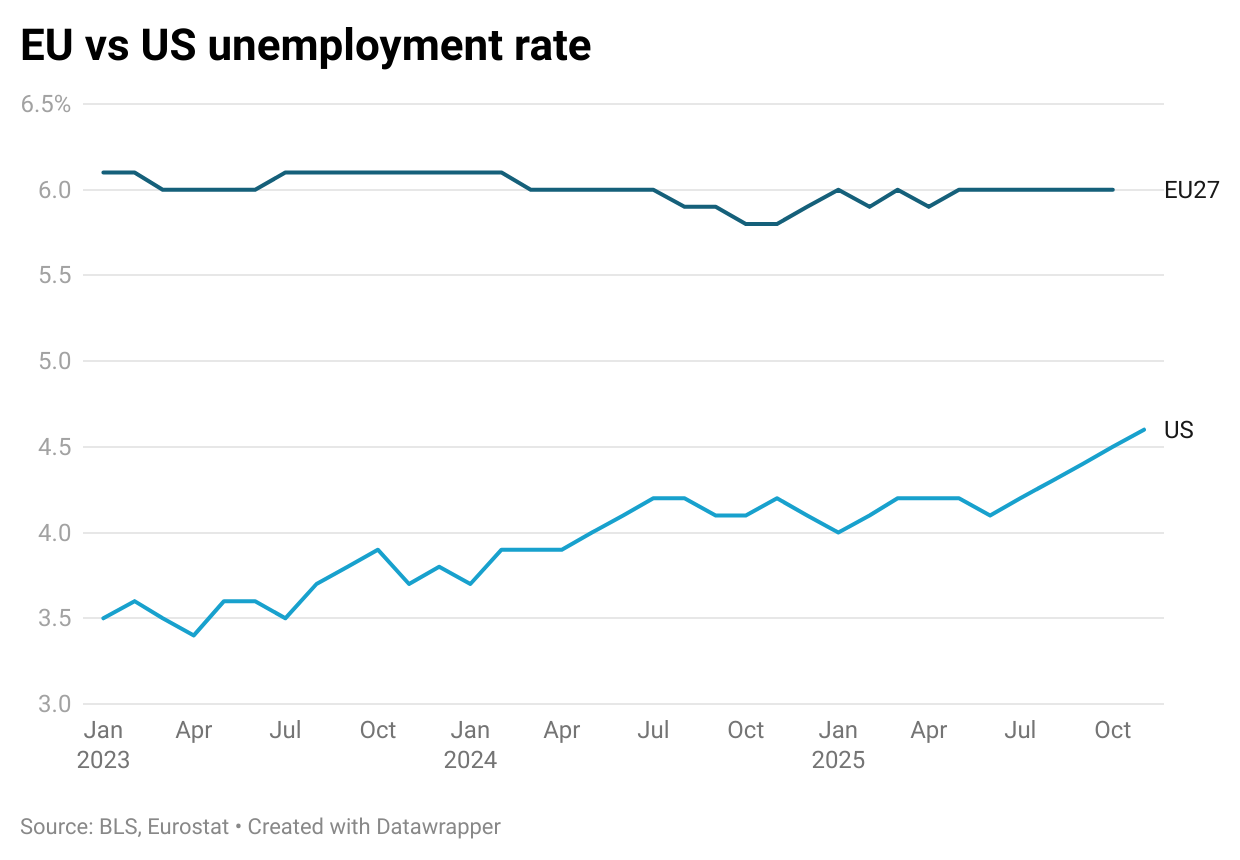

The shrinking US–EU unemployment gap

Plus London’s housing slump, how journalists should use social science, and much more

Welcome to the second issue of The Update. If you like it, please subscribe.

In today’s issue:

US and EU unemployment rates are converging

The US unemployment rate has hit 4.6 percent, the highest since Covid-19. But while American unemployment has increased by more than a percentage point over the last 2.5 years, EU unemployment has stayed flat. As a result, almost half of the gap between them has disappeared, complicating the story of European sclerosis (though cross-country comparisons are hampered by differences in who counts as being in the labor force).

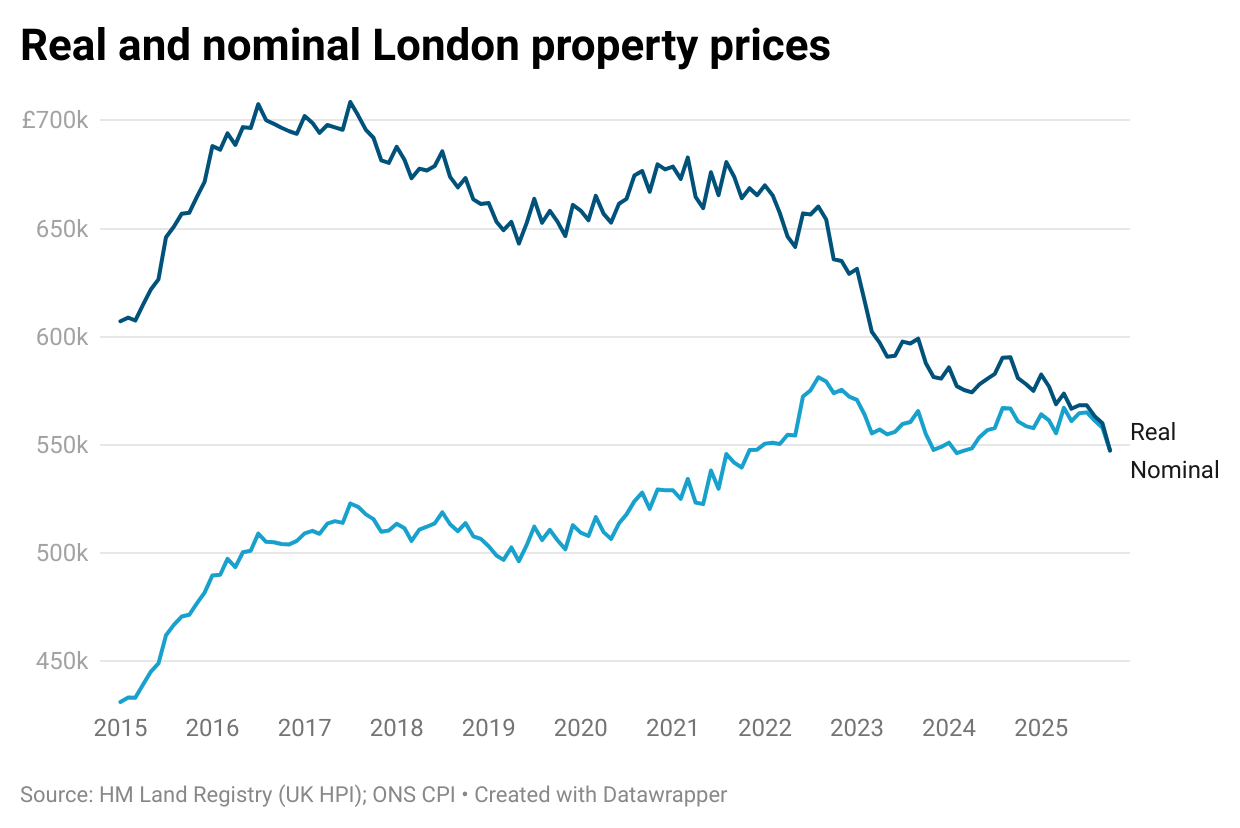

London property prices are down more than 20 percent in real terms

London property prices are down 2.4 percent in the year to October, in contrast to most of the rest of the country, where prices are up. It’s underestimated how weak the trajectory has been for London property prices over the last decade. In real terms, prices are down more than 20 percent since the peak in July 2017.

It’s important to be clear about what this does and doesn’t entail. It does mean that you haven’t become rich by buying a home – which is a common trope – in London for the past few years. But it doesn’t mean that housing has become more affordable. Rents are down by only a few percent in real terms since July 2017, and interest rates are higher today than they were before Covid-19. Prices and affordability should not be conflated.

Matt Yglesias on how journalists should use social science

Should journalists make use of academic social science? And if so, how? In a thoughtful article, Matt Yglesias describes how the norms around these questions have shifted since the turn of the millennium. When he entered journalism, his older colleagues were content with reporting what each side said in policy debates – they didn’t try to establish who was right. But his own generation was more ambitious. Inspired by ‘blogger-professors’ like Paul Krugman, they drew on academic social science to establish the actual facts of the matter.

Personally, I think this was overall a positive development. But Matt makes some astute criticisms of this genre of journalism. One problem is social scientific bias: ‘the massive bias toward wanting to find exciting results’ and ‘a significant ideological bias toward the left’. And he also argues that it suffered from a type of naive positivism, putting too much emphasis on individual studies and too little on general knowledge and common sense.

It seems to me that this reflected the general zeitgeist before the replication crisis. Daniel Kahneman argued forcefully for the primacy of psychological studies over common sense: ‘you have no choice but to accept that the major conclusions of these studies are true’. But since this epistemology wasn’t treated kindly by the replication crisis, we may now be heading toward a synthesis where we – much like Matt suggests – neither ignore academic studies nor trust them blindly, but weigh them carefully against our other beliefs and overall judgment. This seems like epistemic progress to me.

Are ideas getting harder to find?

Karthik Tadepalli writes in Asterisk about why productivity growth has slowed down in advanced economies over the last 50 years. A common answer is that ideas are getting harder to find – that we have to invest more time than before just to maintain the pace of research progress. But according to recent research, the number of breakthrough patents per dollar has actually increased. Tadepalli concludes that the problem isn’t that we’re short of new ideas, but that declining market efficiency prevents them from getting adopted.

I found the article very interesting and admirably clear on a complex topic, but at the same time, I’d have been more convinced if Tadepalli had provided an explanation of the supposedly falling market efficiency. I’m also conscious of the fact that it seems really hard to measure how quickly we discover new ideas. But that said, this is a valuable contribution to an important and difficult question.

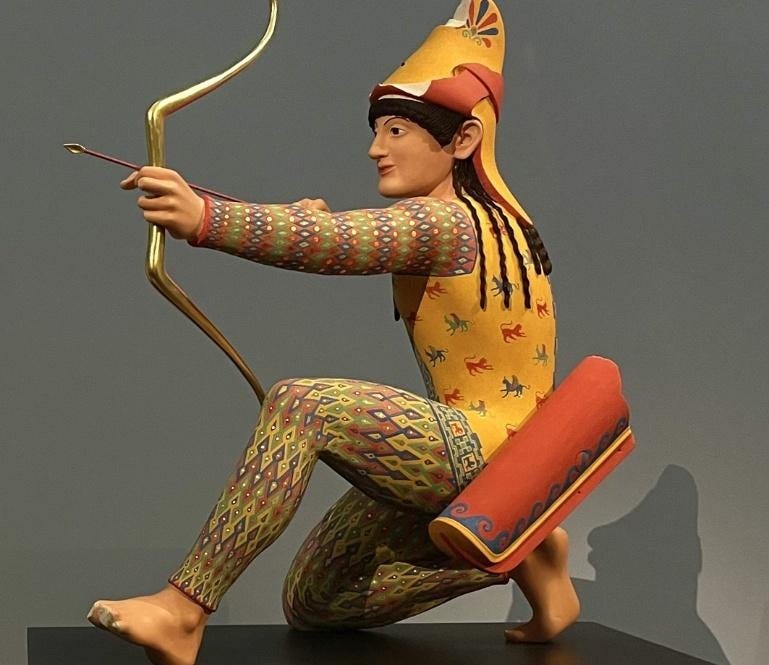

The garish aesthetic of antiquity?

In recent years, it’s been argued that the white Greek and Roman statues were actually garishly painted, reflecting an aesthetic that seems alien to us. It gives a very different picture of antiquity from the one we’re used to. Here is a reconstruction in that style of a Greek statue from c. 500 BC:

But in a new article in Works in Progress, Ralph S Weir rebuts the idea of a garish antiquity. While it’s definitely true that statues were frequently painted, they didn’t look anything like these reconstructions. There are some surviving depictions of statues, and they look much gentler and more subdued. It’s plausible to assume that ancient statues looked like them, Weir concludes.

A substitute for AGI

Are we getting close to artificial general intelligence, AGI? The debate has flared up again after a tweet from Dean Ball about Opus 4.5 in Claude Code meeting OpenAI’s definition of AGI. Ethan Mollick weighed in, tweeting that it has ‘become clear over the past year that the AGI label was never very useful’. I mostly agree with that, as it tends to lead to interminable discussions about definitions. At the same time, I don’t think it’s a coincidence that it keeps being used. People need shorthands for important ideas, and other shorthands (like ‘transformative AI’) have so far not been able to displace the AGI concept.

I think that developing and marketing a better term for ‘AI that is highly advanced or powerful in a relevant sense’ could help the debate about AI progress. But I probably don’t think that the relevant sense is generality. As Ilya Sutskever explained to Dwarkesh Patel, the AGI term was used a decade or two ago in contrast to the narrow systems available at the time. It was often tacitly assumed that if only AI became general, it would completely transform society. But today we have AI systems that in one sense are very general, and yet such a transformation hasn’t occurred. That seems to suggest we need other concepts – maybe relating to agency or coherence, or directly to economic impact.

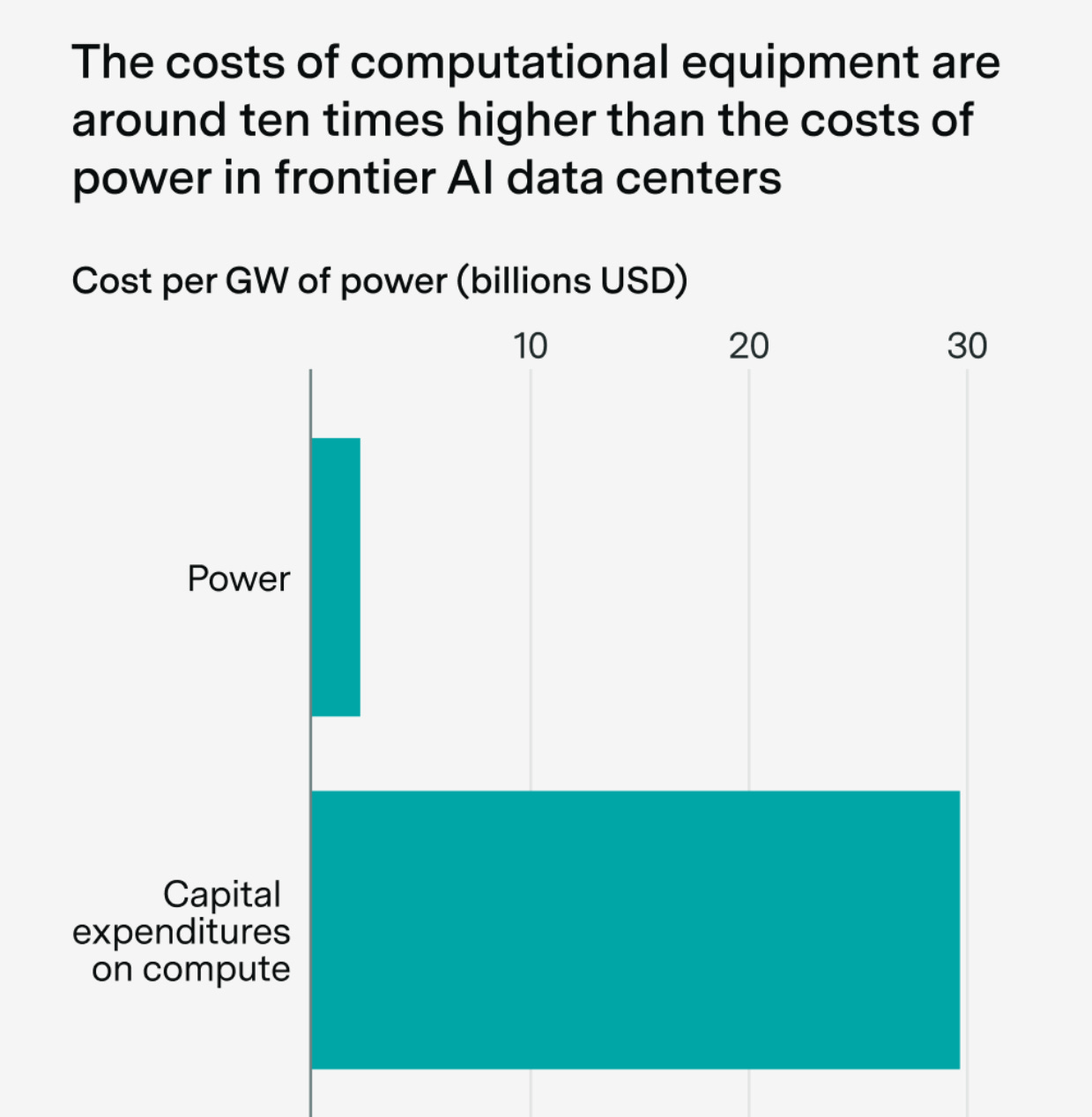

Is power really a problem for American AI?

Many have argued that the US has a fatal weakness in the AI competition with China: electric power. If timelines to transformative AI aren’t very short, then China will ‘win by default’ thanks to its greater power supply, the argument goes. But in a recent article, Epoch AI disputes this notion. It’s true that US power generation hasn’t increased much in recent decades, but that’s because demand has been muted. If it started to increase, then power generation could scale quickly through a variety of energy sources. And perhaps most notably, AI companies’ costs of computational equipment are in any event ten times higher than their power costs. In other words, power may not be the decisive bottleneck for US AI companies.

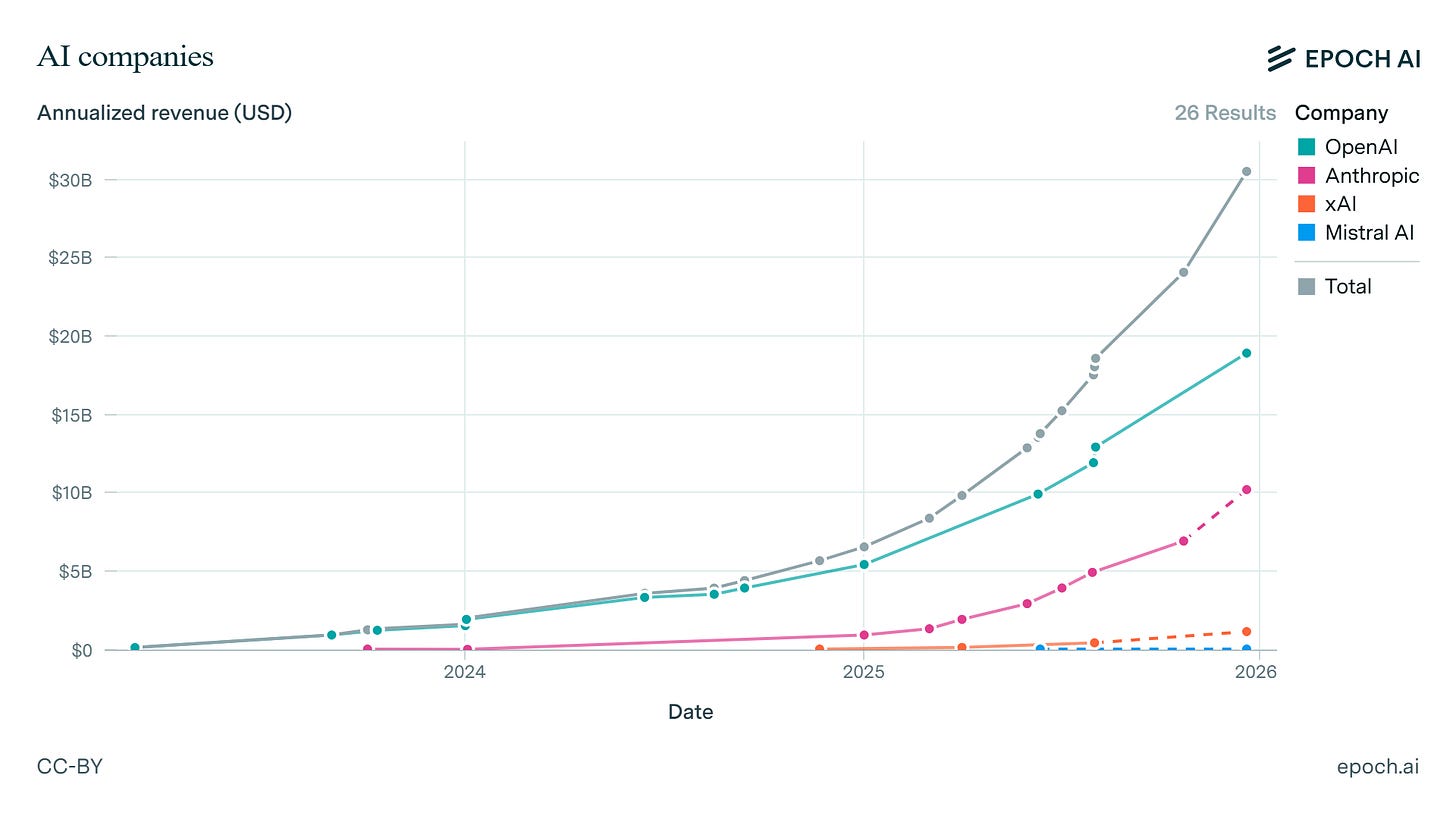

AI companies’ revenue has grown almost fivefold in 2025

Epoch has also updated its chart on AI companies’ revenue, showing that it has increased almost fivefold this year, to around $30 billion. Note that the chart doesn’t include AI-related revenue at larger companies like Google and Meta, presumably because it’s hard to distinguish from other revenue. This means that these figures understate total AI-related revenue.

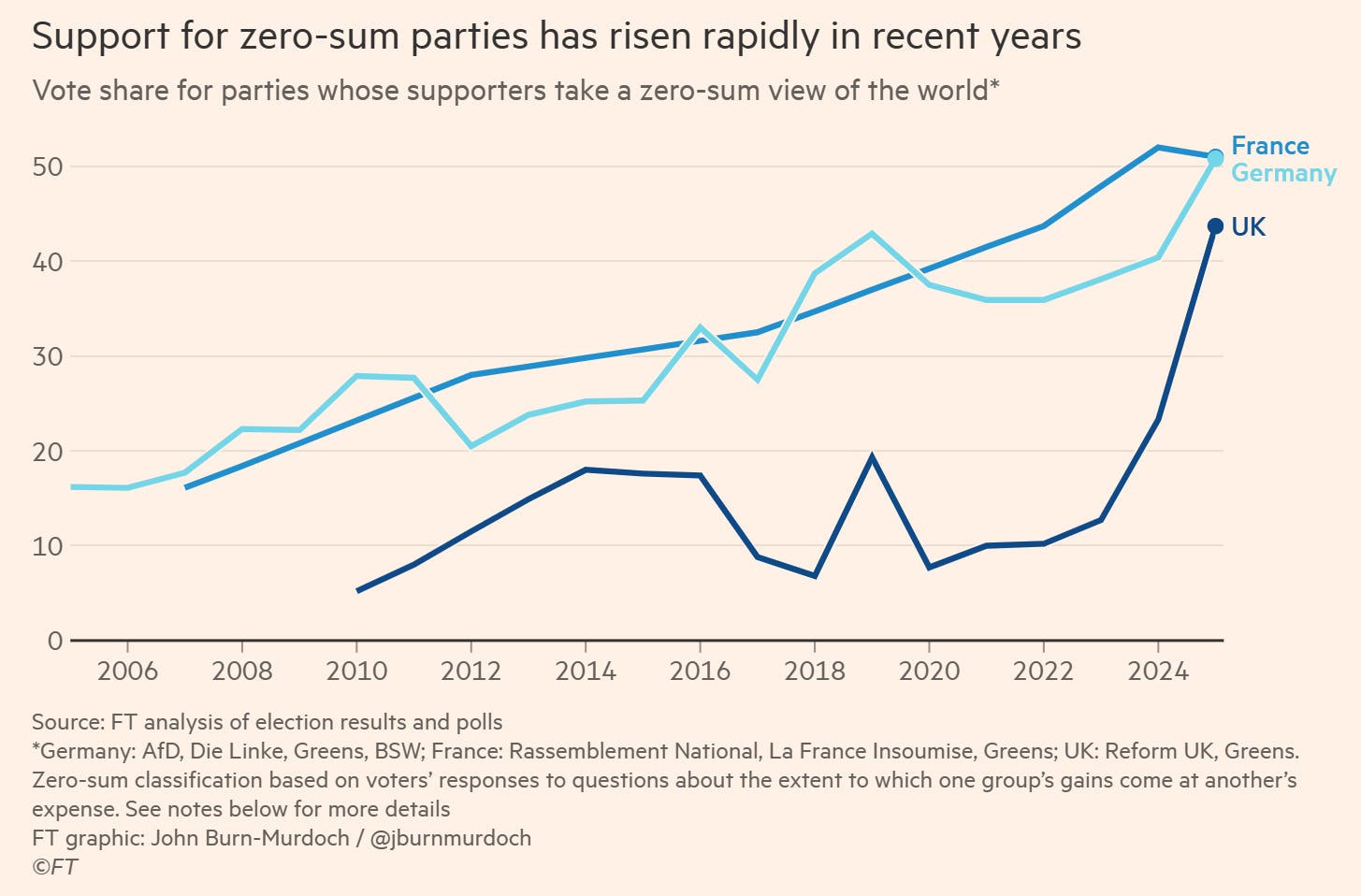

The rise of zero-sum parties

This year has seen increased debate about the zero-sum mindset – the view that one group’s gains come at another’s expense. In today’s Financial Times, John Burn-Murdoch shows that support is rising for parties that cater to this mindset, such as AfD, Die Linke, Reform UK, and the Greens:

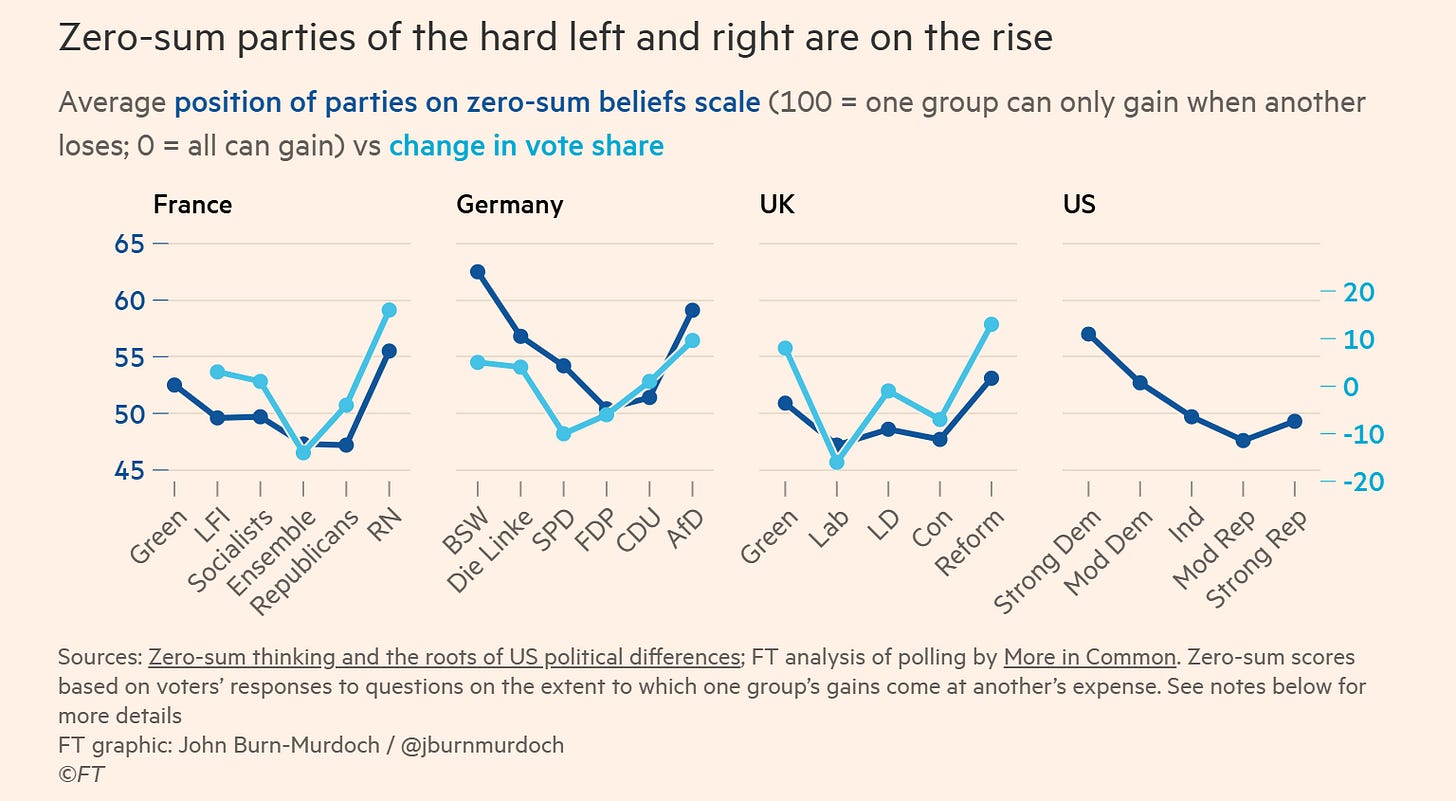

The zero-sum mindset is weakest in the political center, which is currently struggling in many Western countries:

The cultural evolution toward a more convenient language

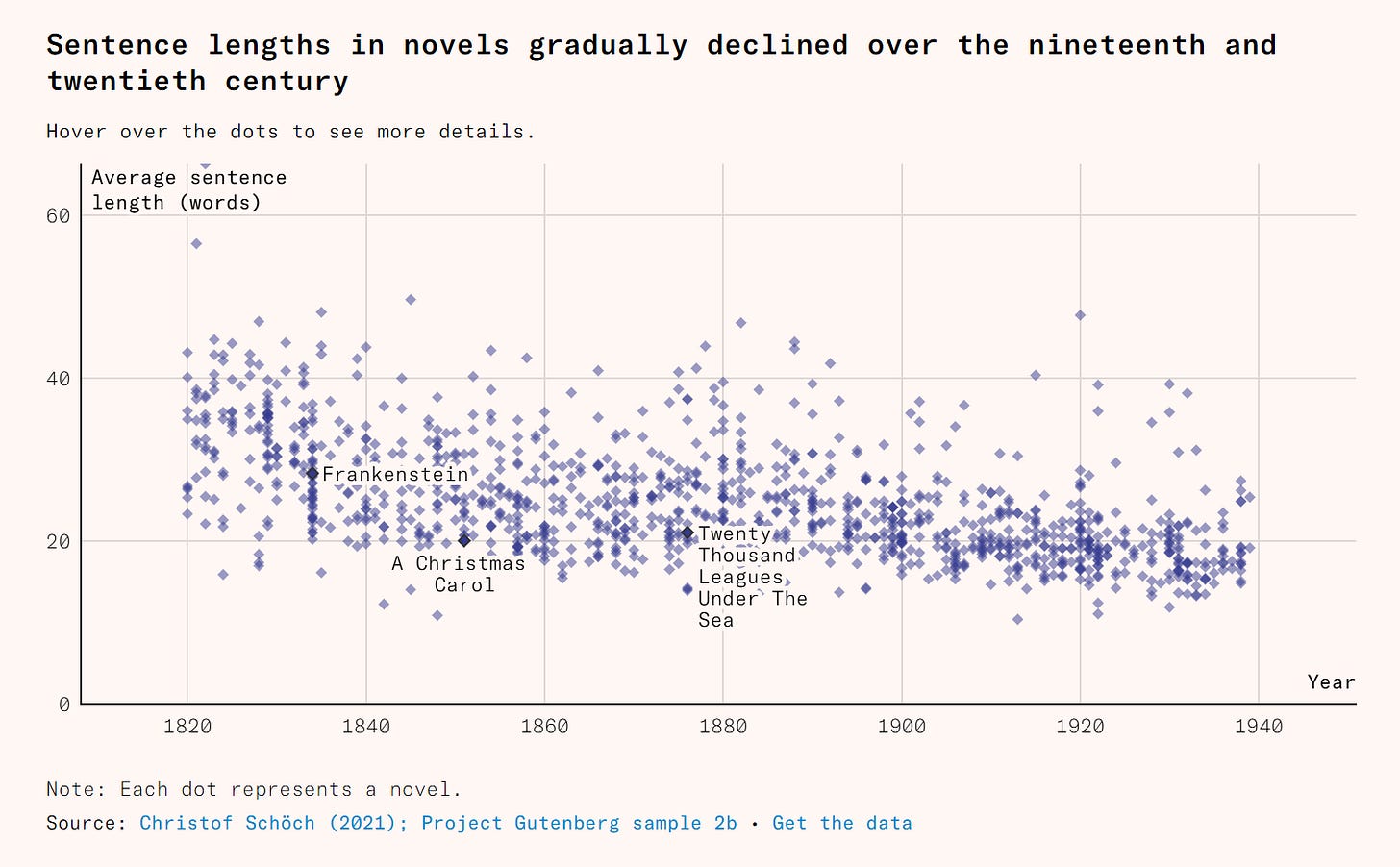

Henry Oliver has a fascinating article in Works in Progress about how English has become easier to read since the sixteenth century. One important change is that people use much shorter sentences than in past centuries.

But surprisingly, Henry argues that this isn’t the main story. The most important shifts were instead a more logical sentence structure and a plainer style with less rhetorical flourish. Henry argues that they were driven by a need for clarity across a variety of institutions, including commerce and religion. The bottom line seems to be that language has undergone a cultural evolution toward greater usefulness, mirroring progress in other domains.

In brief

Gavin Leech, Lauren Gilbert, and Ulkar Aghayeva have published a dashboard on scientific progress during 2025. It’s impressively comprehensive, featuring 202 scientific results along with estimates of the chances that they generalize and the level of impact if they do. There’s also a LessWrong write-up.

Together with a different set of coauthors, Gavin has also published a ‘shallow review of technical AI safety’ for 2025 – a huge effort involving 800 links. In addition, Gavin published his ‘editorial’ for this review a few weeks ago – a synthesizing piece I found particularly valuable.

Job openings for economists are sharply down on the leading JOE listings (largely but not exclusively focused on PhD level roles). There are 20 percent fewer jobs than last year and 42 percent fewer than in 2019. The recent drop is concentrated in academia and the US federal government, while listings have held up better in the private sector.

Bradford Saad, Lucius Caviola, and Will Millership have launched a digital minds newsletter. The first issue is a review of 2025, and it’s very extensive. Clearly, digital minds is a field that’s growing fast on the back of progress in AI.

On the zero-sum graphic: I don't have access to the original article (paywall), but was surprised that the German Green party was included among the zero-sum group. My impression was that they are very explicitly for green growth projects. For what it's worth, I asked ChatGPT ( https://chatgpt.com/share/69479730-9368-8006-b0ae-4c14be625dfb ) and Claude ( https://claude.ai/share/14a0954d-371f-48c8-877d-8dfe41fd12bf ) to classify German parties along the zero-sum axis, and while they agreed for Die Linke, AfD and BSW, they either put the Greens in neutral/complicated or explicitly positive sum.

I think zero-sum is only 1 of 3 lens (and there are more) to look at this. I think status and freedoms also important lens. https://open.substack.com/pub/benyeoh/p/zero-sum-status-and-freedom-three