AI just isn’t good enough to do your job

Plus: forecasting the First World War, the precipitous fall in international adoptions, and more

Welcome to The Update. In today’s issue:

Experts say near-term threat from AI on par with climate change

In the last two years, all American job growth has been in healthcare

In brief: decoding the chemistry of smell, low chance of data center stop, and more

AI just isn’t good enough to do your job

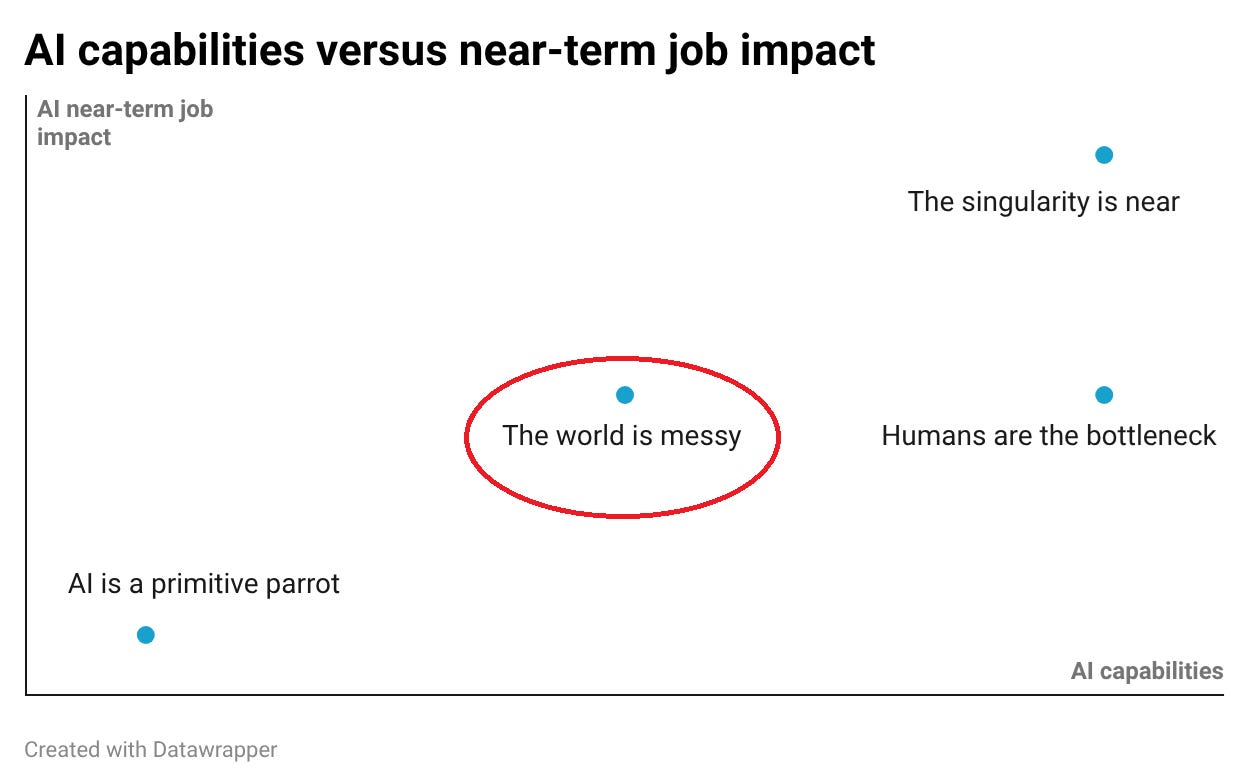

How much job automation are we going to see in the next few years? There is an intense debate about this question, and it can be difficult to orient yourself. Here I clarify the positions and state my own view.

Some people argue that AI is so impressive that massive technological unemployment is imminent. Others take the diametrically opposite view, claiming that AI is still just primitive parroting. I don’t believe in either of these extremes. The biggest optimists definitely overestimate how quickly AI is transforming the labor market, with one of them predicting a Covid-level instant economic shock when ChatGPT was launched in late 2022. On the other hand, my own usage makes me find the view that the latest models are merely primitive parrots increasingly absurd.

There’s a third view that is closer to the truth, but still doesn’t quite hit the mark. This camp argues that AI is indeed impressive, but that its impact on jobs will nevertheless be muted – and claims it’s down to us humans. One argument is that we have quirky preferences, like wanting to be served by other humans. Another is that we’re so irrational – especially on a societal level – that AI adoption will be much slower than the technology allows. Both of these ideas can be found in a recent article by David Oks:

People frequently underrate how inefficient things are in practically any domain, and how frequently these inefficiencies are reducible to bottlenecks caused simply by humans being human. Laws and regulations are obvious bottlenecks. But so are company cultures, and tacit local knowledge, and personal rivalries, and professional norms, and office politics, and national politics, and ossified hierarchies, and bureaucratic rigidities, and the human preference to be with other humans, and the human preference to be with particular humans over others, and the human love of narrative and branding, and the fickle nature of human preferences and tastes, and the severely limited nature of human comprehension. And the biggest bottleneck is simply the human resistance to change: the fact that people don’t like shifting what they’re doing.

As I’ve argued previously, I think our preference to be served by humans is overstated. And though I agree that factors such as norms and regulations are bottlenecks, I think Oks’ framing is skewed toward inefficiency and irrationality. The problem isn’t primarily that we’re poor at solving our problems – it’s that the problems are genuinely hard. For instance, bureaucratic rigidities are largely a byproduct of the fact that laws need to be predictable while covering a variety of cases.

The world is messy to a degree we often fail to appreciate. When we observe other people’s jobs from a distance, we tend to underestimate their complexity. This can lead us to think that automation should be easy – and to blame human foibles when it is delayed.

View of the World from 9th Avenue by Saul Steinberg.

My perspective can also deflate some of the hype around how good AI systems have become. While they’re certainly not primitive parrots, they still have a fairly limited range of capabilities. If we look past simplistic benchmarks and consider everything you need to master to automate an average job, even the best models start to look less impressive.

Over the long term, this lens on AI has thoroughgoing implications for the economy. Once we actually have AI systems that can navigate reality in all of its complexity, I don’t think their impact will be blunted by quirky human preferences or institutional irrationalities. Unless there’s a concerted effort to stop AI from being developed or deployed, it will likely lead to widespread automation of human jobs.

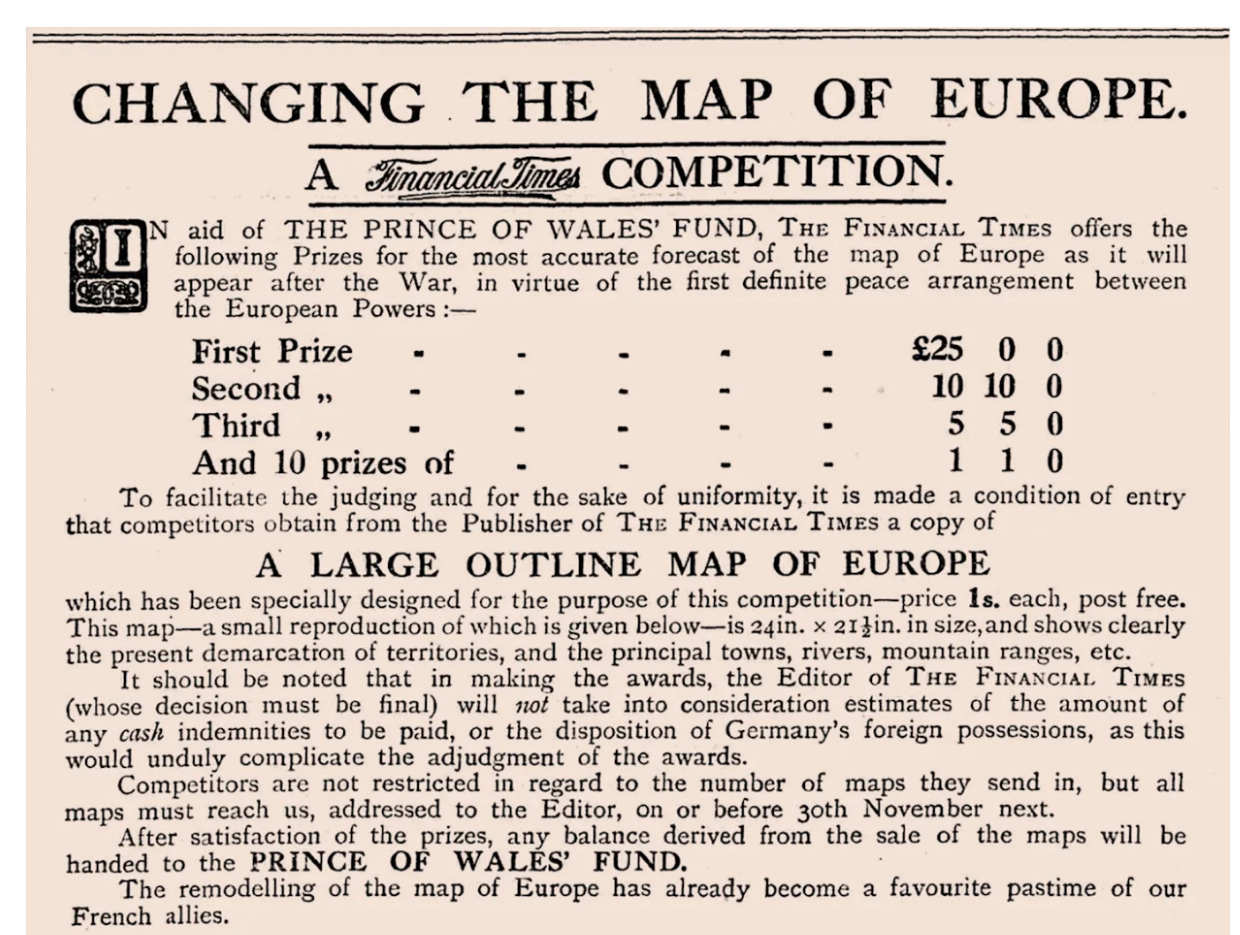

Forecasting the First World War

Prediction markets have grown increasingly popular in recent years, but putting money on predictions is nothing new. In 1914, the Financial Times launched a competition to forecast the border changes of the Great War, later known as the First World War. Participants were asked to sketch their best guess of the post-war borders on a map they could buy from the FT for one shilling (roughly £7.50 in today’s money).

24 inches by 21.5 inches (61 cm by 54.5 cm).

Impartial truth-seeking doesn’t seem to have been celebrated: maps suggesting a German win were viewed as ‘croakers’ lacking in patriotism, and many had unrealistic hopes for Allied gains.

As the various peace conferences after the First World War took their time, the FT only published the results in 1921. ‘No map sent in is even approximately accurate’, it concluded. While the majority was right that France would gain Alsace–Lorraine, all participants had failed to predict Russia’s enormous territorial losses in the wake of the 1917 revolution.

1914 borders in gray, 1921 borders in orange.

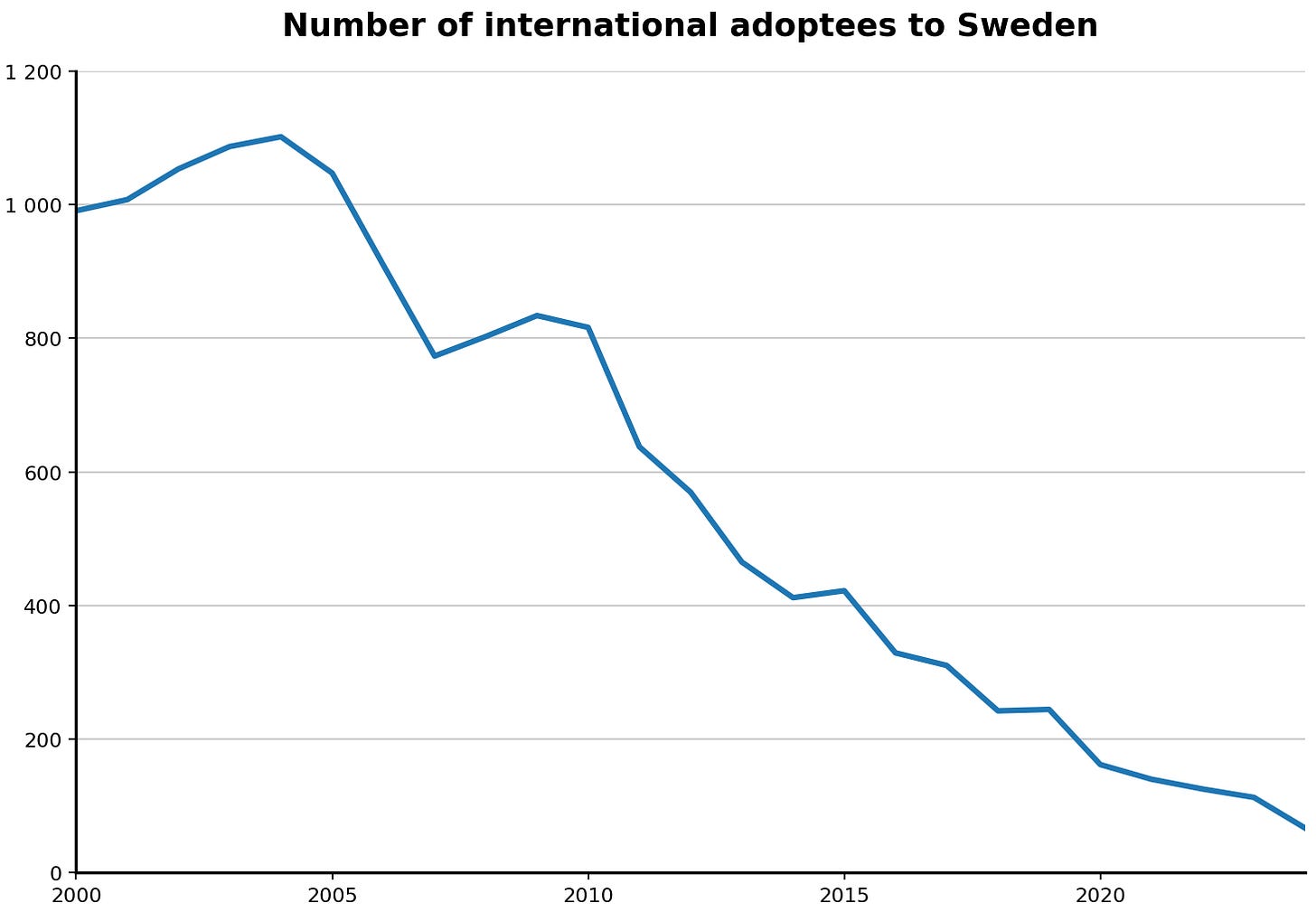

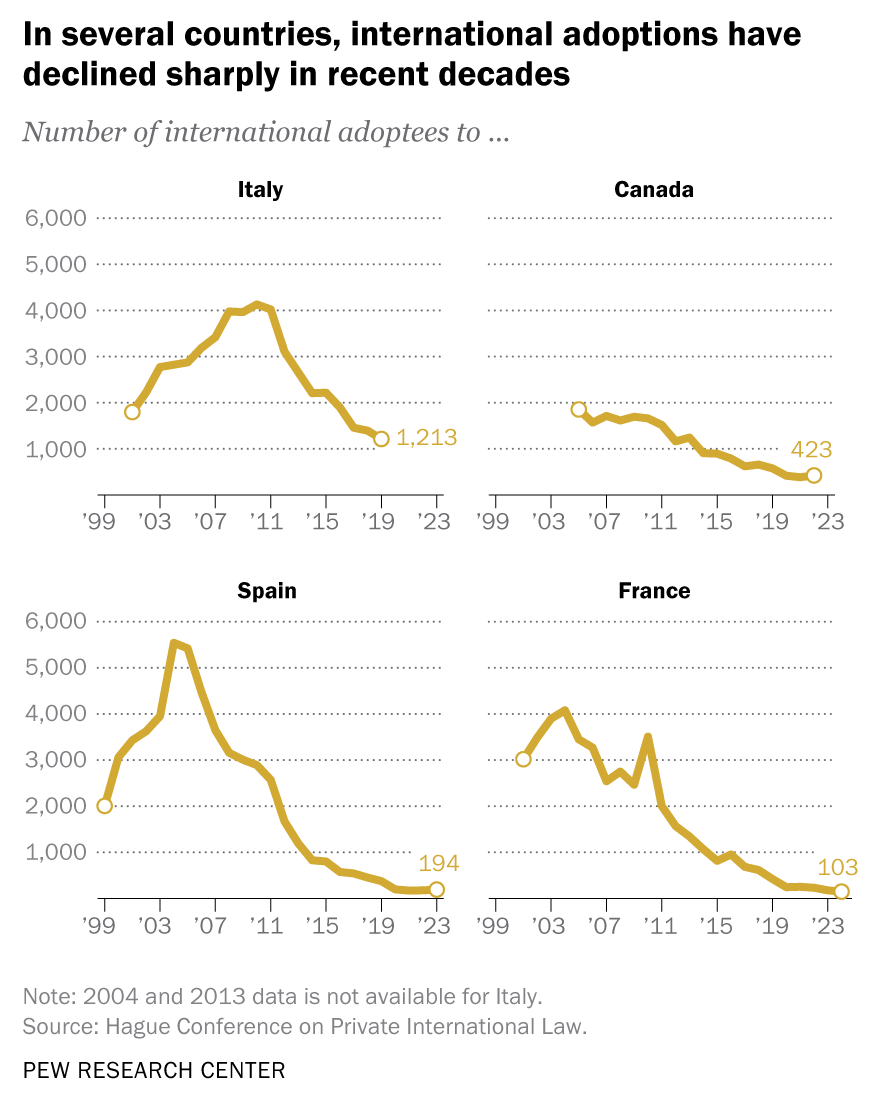

The precipitous fall in international adoptions

Statistics Sweden has published new data on the remarkable decline in international adoptions to Sweden – almost 95 percent since 2004.

Adapted from Statistics Sweden.

This mirrors the pattern in other Western countries:

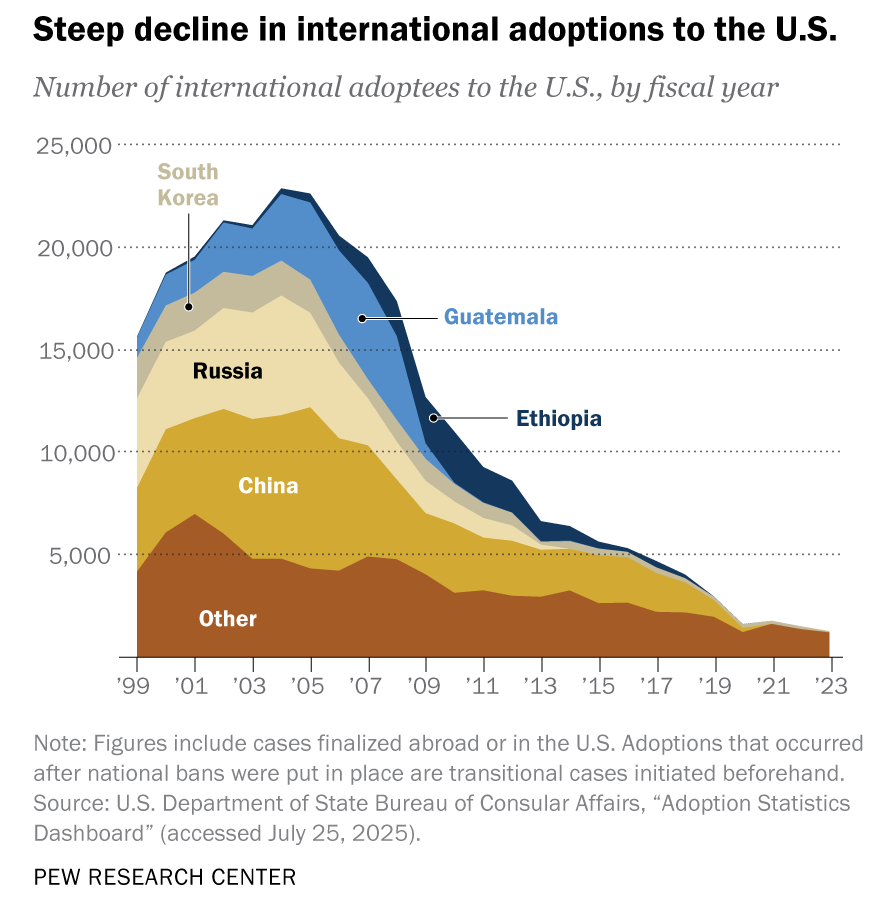

Part of the reason is that several major sending countries have reduced or banned international adoptions, including China, Ethiopia, and Guatemala:

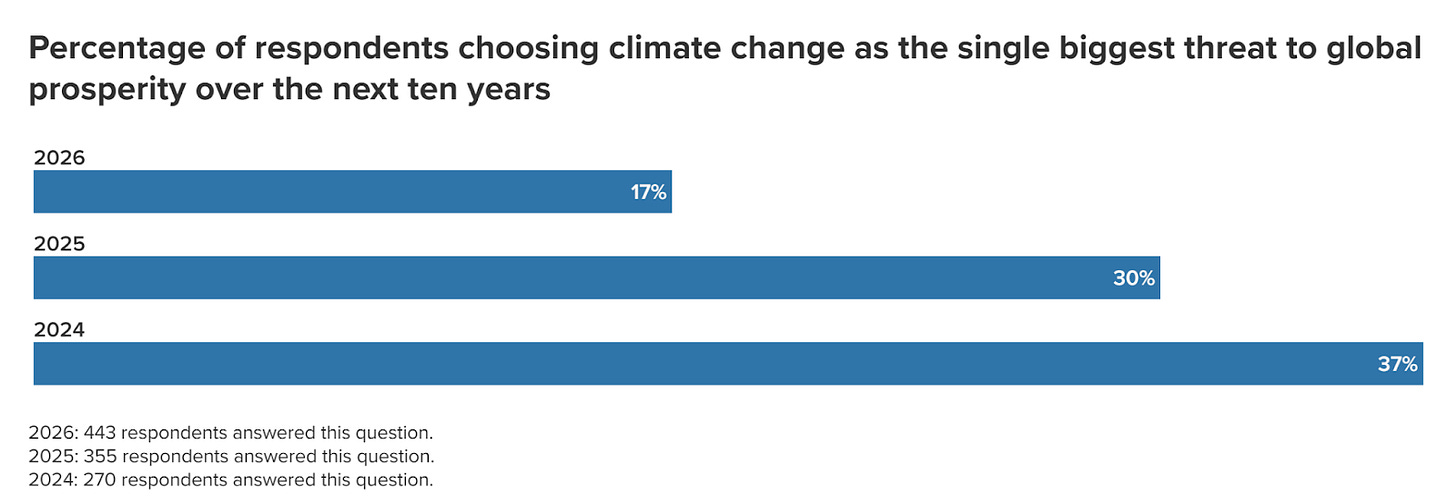

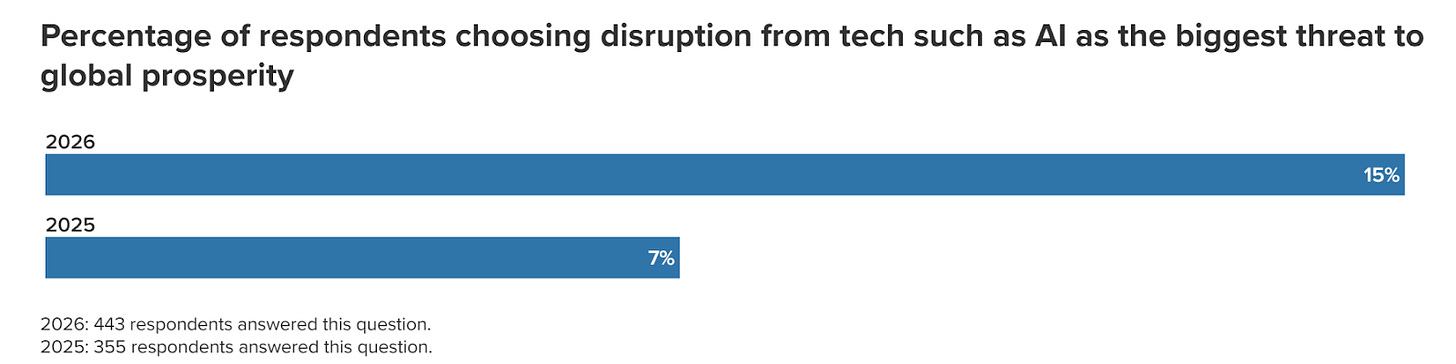

Experts say near-term threat from AI on par with climate change

In an annual survey from the Atlantic Council, the fraction of experts who believe that climate change is the greatest near-term threat to global prosperity is now 17 percent, less than half of what it was two years ago.

At the same time, the fraction viewing AI as the biggest near-term threat has more than doubled since last year, to 15 percent.

The threat that got the largest share of votes, 30 percent, was war between major powers.

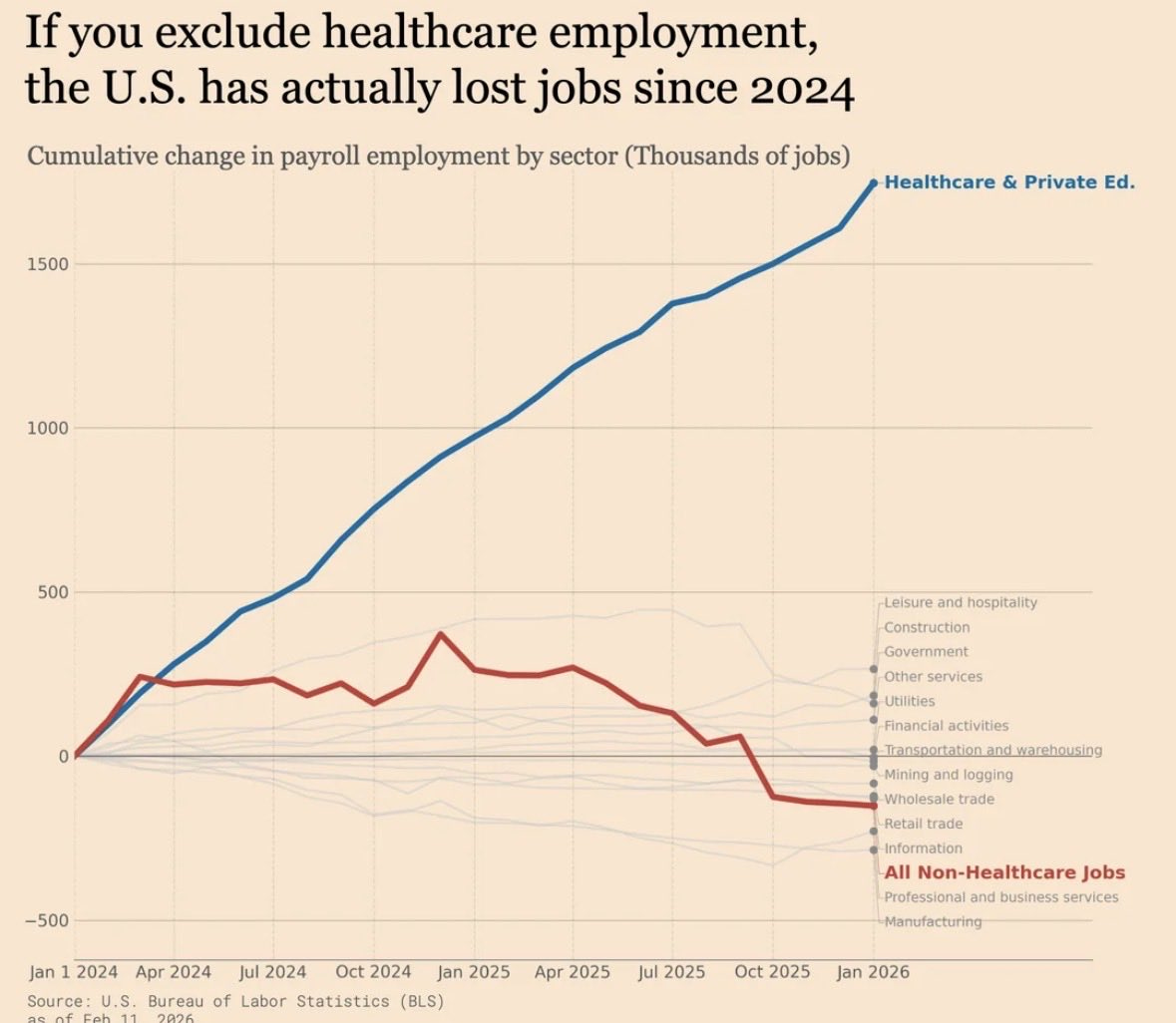

In the last two years, all American job growth has been in healthcare

The American labor market is weak, and most industries are losing jobs. But healthcare employment is a notable exception, as it tends to grow regardless of economic conditions.

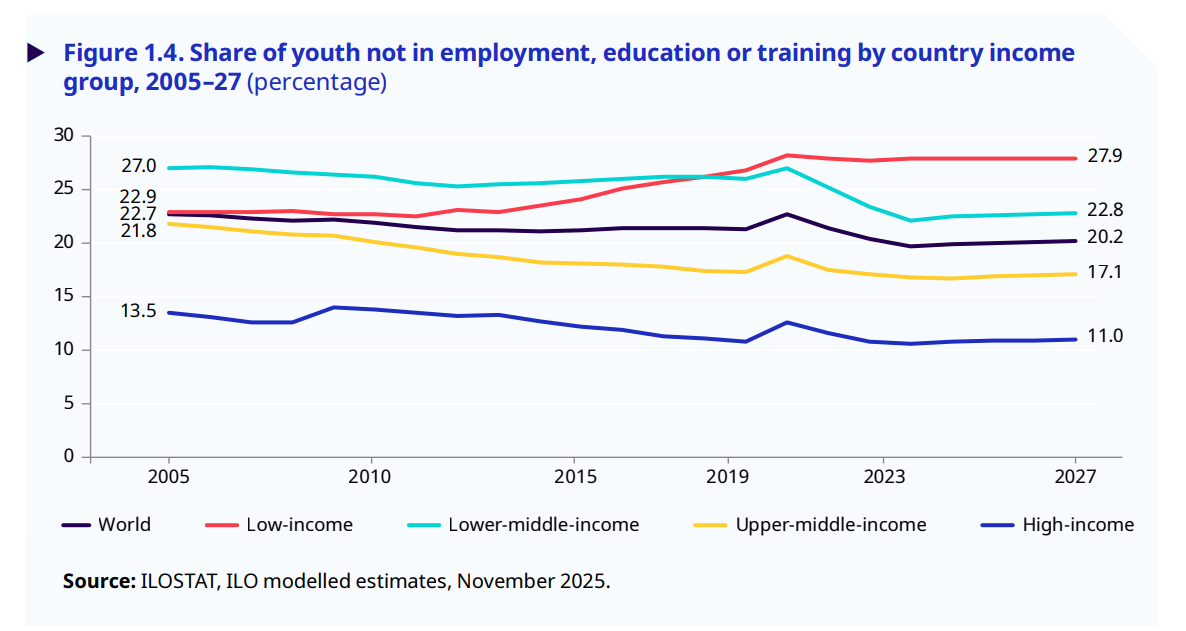

Poorer countries have more inactive young people

Less prosperous countries are less efficient in all sorts of ways, including in how they make use of their human capital. Data from the International Labour Organization shows that 28 percent of young people (aged 15–24) in low-income countries are not in employment, education, or training. By contrast, that figure is only 11 percent in high-income countries.

Via Adam Tooze.

In brief

Using AI to identify the molecular structures of smells, and design new ones

Alberta may hold a secession referendum but is unlikely to leave Canada

What Coefficient Giving’s Abundance and Growth Team is reading

FDA encourages Bayesian methods to include all relevant data in drug trials

Sentinel: 4 percent chance of a federal stop on data center construction before 2029

12 percent chance a Chinese AI model will be top three in capability this year

That’s all for today. If you like The Update, please subscribe – it’s free.

Great on "the world is messy"

Example, physical therapy. It looks like people should do PT with various orthopedic issues. But most don't do and the superficial explanation is stupidity of lack of self control.

I've you get closer you see:

Many orthopedic issues aren't as easy to diagnose.

PT is intricate, and getting the proper Ilan, instructions and dynamic adjustments over time is really hard.

Many PT professionals are no good

This I've noticed with the experience of myself and friends....

Good piece. I really liked Ok's post but agree with you on this: "Oks’ framing is skewed toward inefficiency and irrationality. The problem isn’t primarily that we’re poor at solving our problems – it’s that the problems are genuinely hard."